About five months ago, a 29-year-old influencer named Ashton Hall uploaded a video detailing his five-hour morning routine. It exploded on the internet. Beginning precisely at 3:50 a.m., the ritual featured a sequence of indulgences that included rubbing banana peels on his face, then plunging it into a bowl of ice, topped off with an $8 bottle of Saratoga sparkling water. The video garnered more than a billion views across platforms, inspired hundreds of reaction videos, and even earned a winking nod from the CEO of Saratoga, saying he was “loving the memes.”

Hall’s TikTok, a cocktail of luxury self-care and stoic sermonising, quickly turned into a kind of cultural Rorschach test. Depending on whom you ask, it’s either parody, performance, or peak hustle culture. But to some, it marked a turning point: the rise of a new “alpha male” aesthetic; a pristine, hyper-optimised masculinity that lives in spotless apartments and never breaks a sweat, even when it’s bathing in ice water.

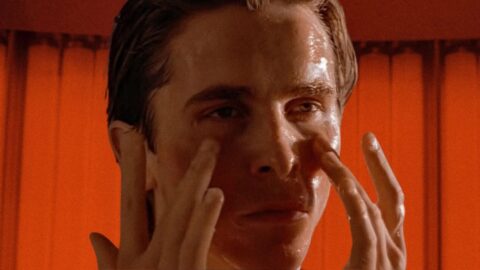

If that routine sounds strangely familiar to anyone over 35, it’s no coincidence. Mary Harron’s 2000 film American Psycho opens with a similar one. Patrick Bateman, the film’s eerily composed antihero, guides us through his carefully curated morning regimen: a thousand crunches, a suite of designer skincare products (no alcohol, it makes you look old), and a tone that hovers between spiritual devotion and dead-eyed vanity. Back when the film was released, it played like a confounding satire. Today, it reads like lifestyle content. The unsettling part isn’t just how closely Hall echoes Bateman. It’s that even as his routine gets widely mocked, it still moves product: Saratoga water sales spiked, his Instagram following nears 18 million, and he credits the regimen with making him a millionaire. Applauded, with devoted aspiration.

American Psycho turns 25 this year, and its anniversary screening at Tribeca, fresh off the close of its 2025 edition this past weekend, felt like less of a retrospective than a cultural alarm bell. American Psycho hasn’t dated; it’s evolved. Watching it in 2025 doesn’t just feel relevant, it feels eerily predictive, as though Bateman’s world never really ended. It just migrated to your feed.

Which is why the timing feels strangely apt: Luca Guadagnino has just signed on to direct a new version of the film, with White Lotus (Mike White, 2021-) star Patrick Schwarzenegger reportedly already lobbying to play Bateman. But the question now isn’t whether American Psycho needs an updated makeover, but what it means to repackage that former critique of masculinity-as-performance at a time when that very performance has become both hyper-self-aware and wildly profitable.

A Queer Feminist Gaze

Adapted by Mary Harron and co-writer Guinevere Turner from Bret Easton Ellis’s 1991 already-infamous novel, the film was received as a blood-soaked takedown of 1980s Wall Street excess. Horror played through the language of satire. But many deemed it unfilmable. The narrative, largely internal and deeply unreliable, offered a portrait of a man whose identity was as superficial as the business cards he fetishised. The danger wasn’t in what he did, but in how little anyone seemed to notice.

What many missed then was that American Psycho was never really about murder. It was about masculinity in its most hollowed-out form, the early tremor of a ticking bomb whose fallout bred the performance gurus and alpha grifters of today. The Bateman archetype didn’t disappear; it turned into men like Andrew Tate, who sell detachment as strength and dominance as self-worth. The fact that the novel was written by a gay man and the film adapted by a feminist filmmaker is not incidental. It’s essential to understanding how a story drenched in hypermasculinity ends up dismantling it from within. According to Harron, being queer gave Ellis the distance to notice the homoerotic choreography behind all that alpha posturing. Ellis, not yet publicly out at the time of the book’s release, infused Bateman’s fastidious masculinity with a kind of unspoken tension. Then Harron zeroed in on that tension, reshaping the book’s cynicism into something that mocked its subject even as it let him speak.

But Harron didn’t just adapt Ellis. She rescued his story from the clutches of Hollywood misfires. Earlier attempts to bring the novel to the big screen had involved Oliver Stone and Leonardo DiCaprio, fresh off Titanic (James Cameron, 1997), with a script that risked turning Bateman into just another charismatic killer. Harron, who at the time had made only one feature — the 1996 now-obscure cult classic I Shot Andy Warhol, a rough-edged portrait of radical feminist Valerie Solanas, who became known for her S.C.U.M. Manifesto, suggesting that men were a biological mistake and should have their penises cut off — came in with different instincts. She gets into the picture reading American Psycho not as provocation but as diagnosis, stripping the novel of its edgelord nihilism and rebuilding it with scalpel precision.

And this, perhaps, is why the film has aged so uncannily well. In a recent interview with GQ, Harron admitted she still finds it surreal how many men idolise Bateman. “Wall Street bros” still quote him unironically, treating Bateman like some kind of aspirational power fantasy rather than the punchline. The character’s hyper-clean surfaces and hollow charm have been rebranded as life goals.

When American Psycho premiered at Sundance in 2000, it left audiences unsure whether they were supposed to laugh or recoil. Harron later said she had never encountered that kind of hostility from a crowd before. In a New York Times essay written at the time, she recalled people confronting her with questions like, “How would you feel if someone saw your movie and went out and killed someone?” It wasn’t just criticism, it was a hysterical moral panic. Some critics wrote it off entirely. The Washington Post dismissed the film as “nothing more than bloodshed and intellectually secondhand implications about materialism, conformity and misogyny.” Stephanie Zacharek, writing for Salon, said that everything in the film is “a broad joke” and noted that Huey Lewis had reportedly pulled “Hip to Be Square” from the soundtrack, apparently eager to distance himself from the film.

But time did what time does. Slowly, the film became a cult object, celebrated for the very things that once unsettled: its deadpan wit, its unnervingly precise take on greed and masculine insecurity, its ability to say the unspeakable with a smile.

Ironic Fluency

Another takeaway from its 25th anniversary is how American Psycho has taken on a new life as a totem within meme culture, almost prophetic in anticipating how meaning fractures and reassembles in the digital age. The film’s deadpan delivery and moments of surreal absurdity have turned its most famous lines (“I have to return some videotapes” “Is that a raincoat?” or “Try getting a reservation at Dorsia now, you fucking stupid bastard!”) into snippets that circulate stripped of context, transformed into detached gestures of cool.

These fragments have become social currency, especially among younger men who seem less interested in the satire and more drawn to Bateman’s polished veneer as an aspirational ideal. This dissonance between Harron’s sharp critique and the film’s remix into meme fodder reveals a culture fluent in irony but deeply resistant to sincerity. In that sense, the film wasn’t just a snapshot of ‘80s Wall Street excess — it was a premonition of how meaning would splinter and spread in a world where identity, humour and critique blur into one another endlessly online.

What Ellis provoked, Harron clarified. She understood that Bateman wasn’t terrifying because he was a killer. He was terrifying because he was banal. Ordinary. The product of a system that rewarded image over interiority, optics over ethics. Ashton Hall’s five-hour routine isn’t an outlier. It’s a manifestation of a culture that packages discipline as aesthetic, selling self-optimisation as identity. The rituals of skincare and cold plunges aren’t the real problem. But the artificial intensity with which they’re broadcast, the sense that a life must be seen to be real, feels like Bateman in a bathrobe, holding a ring light.

Twenty-five years on, American Psycho reveals how the narcissism of the 1980s metastasised into today’s algorithmic identity crises. We’re still mistaking surface for substance, likes for love and productivity for value. Bateman wasn’t just a psychopath. He was a product. And we haven’t stopped buying.

Wellington Almeida is a programmer, a film writer and a devoted cat lover.