By unhappy coincidence, I started this piece shortly after hearing Terence Davies had died. Davies, whose elegant pessimism was informed by the repressive milieu of his Liverpool upbringing, remained fervently fixed on weaving threads between personal and collective visions of the past as a site of enduring trauma. There’s a thematic consonance, if markedly different aesthetic approach, between Davies and the newest mid and short-length work from Wang Bing, Pedro Costa and the late Jean-Luc Godard, presented as one package here at the NYFF. In their shorts, these filmmakers all navigate their respective national histories to contend with traces left by those who are effaced yet not silenced.

Adieu au Godard

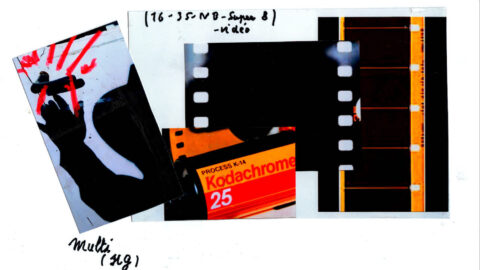

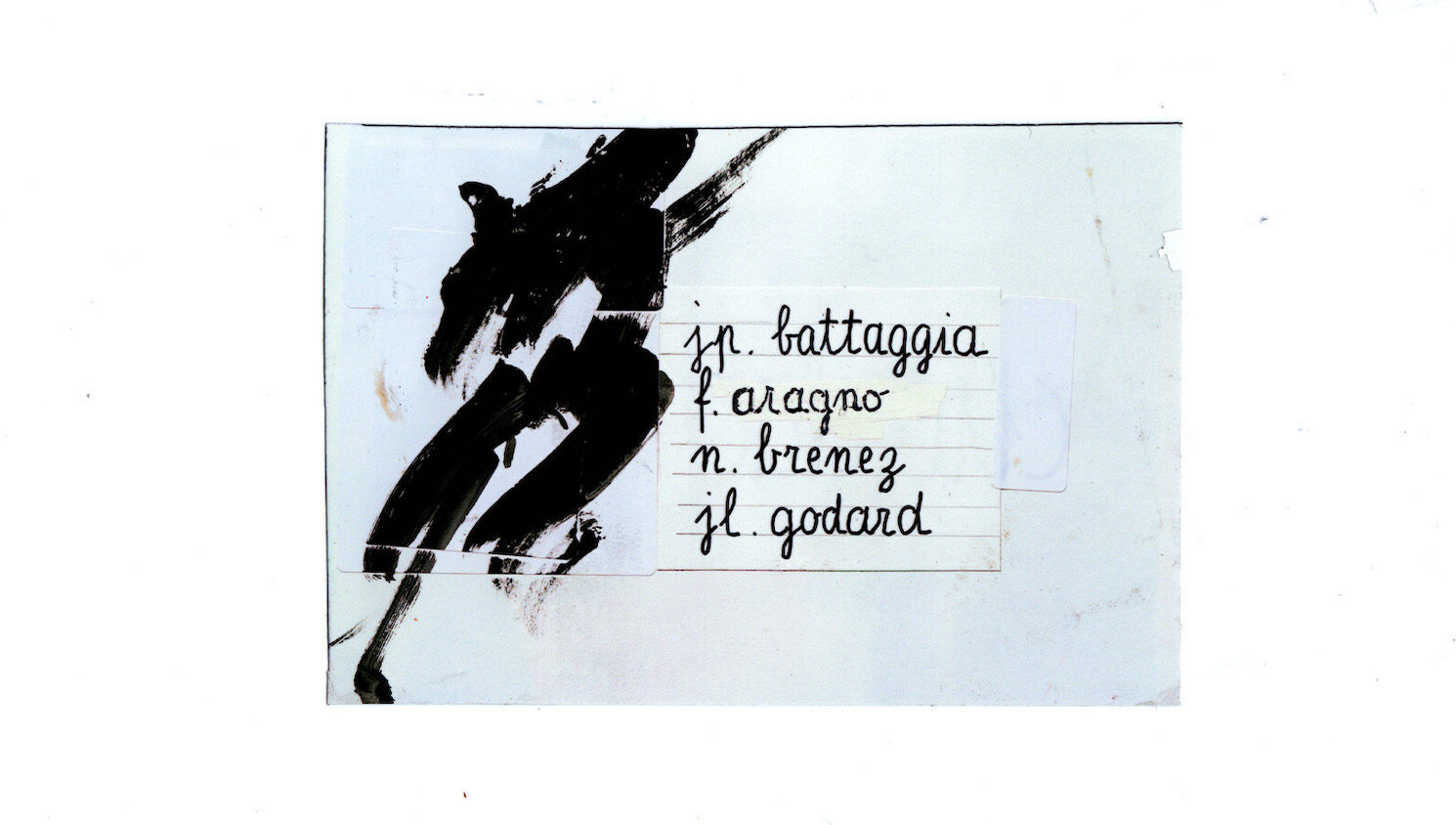

Writing about Godard has always posed a challenge to the critic tasked with reviewing his work. His prickly provocations were mimicked by generations of filmmakers, but the complexity of those barbs has been rarely matched. Trailer of a Film That Will Never Exist: Phony Wars (2023, feature and above) is hardly the apex of his lifelong vocation to probe the boundaries of his (or any) artistic medium. Ascribing such finality to any of Godard’s work would be to miss entirely the intellectual rigour that made him such a vital voice in the second half of the 20th century.

The central figure of the project is Charles Pilsnier, a Belgian writer who was expelled from the Communist Party for his Trotskyist sympathies. Godard sought to use Pilsnier’s novel Faux Passeports (1937) as a springboard for creating a film which would be spiritually akin to Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Silence de la Mer (1949). A very different sort of silence pervades Godard’s collection of Polaroids and violent defacements of Franz Kline’s abstract paintings. Godard describes Pilsnier as a “painter of faces,” and his linkage between Pilsnier, Kline and Melville indicates an interest in identifying a humanist strain within avant-garde practices of the past century.

Cryptic French and Russian-speaking voices reference Hannah Arendt and commonalities between Sarajevo and Palestine, echoing Godard’s long-voiced dismay at cinema’s failure to prevent wide-scale atrocities from re-occurring. The title of Phony Wars indicates a troubling trend of epistemic uncertainty which has ushered in global oppression. But the prevailing tone of this film is not one of dread but sorrow: these ghostly impressions feel drawn from a brilliant mind reaching the end of its capacity for discursive thinking. But its deliberately incomplete structure puts the onus of political engagement squarely on our shoulders, impelling us to let go of Godard the icon while saying goodbye to Godard the man. “It’s your business and not mine,” the filmmaker intones, “to rein over the absence.”

Wang Bing Goes Brechtian

Absence figures dominantly in Wang Bing’s Man in Black (2023, above). Wang’s atypically short sixty-minute portrait of avant-garde composer Wang Xilin mines familiar subject matter in foregrounding a survivor of China’s Cultural Revolution. Yet its comparatively narrow focus is not the only thing distinguishing it from grander explorations of the topic like The Ditch (2010) and Dead Souls (2018). Indeed, the bifurcated structure of Wang’s first film shot outside of Asia boldly blends performance and confessional into a disquieting expression of curdled rage.

For the first thirty minutes, Xilin doesn’t utter a word as he ambles, completely naked, through the empty auditorium of the Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord in Paris. The camera glides around and over Xilin’s body, which contains vestigial traces of the violence he endured in a labour camp. Xilin regales the camera with stories of the torture he experienced, as well as the mentors at the Shanghai Conservatory who committed suicide during the government’s crackdown on allegedly counter-revolutionary subversives. Excerpts from his symphonies often overwhelm the soundtrack, supplanting Xilin’s words with an aural approximation of agony.

Throughout his work, Wang Bing’s multivalent use of duration directs the historical concerns driving each project toward a distinct focus on how his subjects carry their trauma within their bodies. But as far as I can recall, Man in Black is unique in its foregrounding of performance (oral and physical) as a tool for conveying that trauma. Both filmmaker and subject adopt a Brechtian form of address and, like Godard, cull shards of the past to evoke a fragmented, post-modern confrontation with the present. For Xilin, the historical trajectory of his trauma is distilled to the “idealism” and, ultimately, “betrayal” of Communism in a homeland which effectively consigned him to exile.

Pedro Costa Under The Volcano

Displacement and performance also commingle in Pedro Costa’s The Daughters of Fire (2023, above). Like Phony Wars, Costa’s triptych of three sisters (Elizabeth Pinard, Alice Costa, and Karyna Gomes) singing against the soundstage simulacrum of a volcanic inferno is a proof-of-concept reel for a potential feature. Yet the film’s austerity heightens an operatic intensity that, when seen after the preceding films, is emotionally overwhelming.

For most of the eight-minute runtime, the three sisters’ oratório is performed over an arrangement of Biagio Marini’s “Passacaglia” by the group Os Músicos do Tejo. Their contrapuntal vocals repeat phrases like, “One day there will come a time when we know why we suffer, and the mystery will end,” with Alice the lone figure filmed in a wide shot in the centre frame. Through subtle differences in expression and lighting, the static portraits of each woman complement the film’s sonic shift into spoken recitation against a Ukrainian lullaby.

Costa has attributed this latter inclusion to violinist Denys Stetsenko. It’s a detail which speaks to Costa’s methodology more than any timely geopolitical reference. Costa opts to deploy classical formalism in service of his largely immigrant collaborators. The implications of wedding various aspects of a communal, cosmopolitan past threatened by a “fascistic” cultural hegemony is a fundamentally political gesture.

Costa’s allegiance to the Cape Verdean immigrants he deems central to Portugal’s transformation in the preceding century is sealed by a breathtaking coup: a cut to silent archival footage of the Pico do Fogo volcano’s eruption, captured by ethnographer Orlando Ribeiro in 1951. We see survivors of the disaster swathed in rags, staring intensely at Ribeiro’s camera. Their stories are incomplete since, as the women earlier remark, “the dead cannot answer.” But as all three of these featurettes testify, cinema can renew their legacy for the living.

Nick Kouhi is a programmer and critic based in Minneapolis, Minnesota