The night before I took the Eurostar from London to Amsterdam, eager to attend IDFA for the first time, I was curious, if not anxious, to see, learn and/or read about what an international film festival as important and influential as IDFA would have to say about the events of the last month.

It was exactly one month since Israel began its brutal assault on the Gaza Strip, itself a continuation of 75 years of apartheid rule and genocidal violence. And while calls for an immediate ceasefire rang across the world for just as long, IDFA itself hadn’t yet released any kind of statement on the matter.

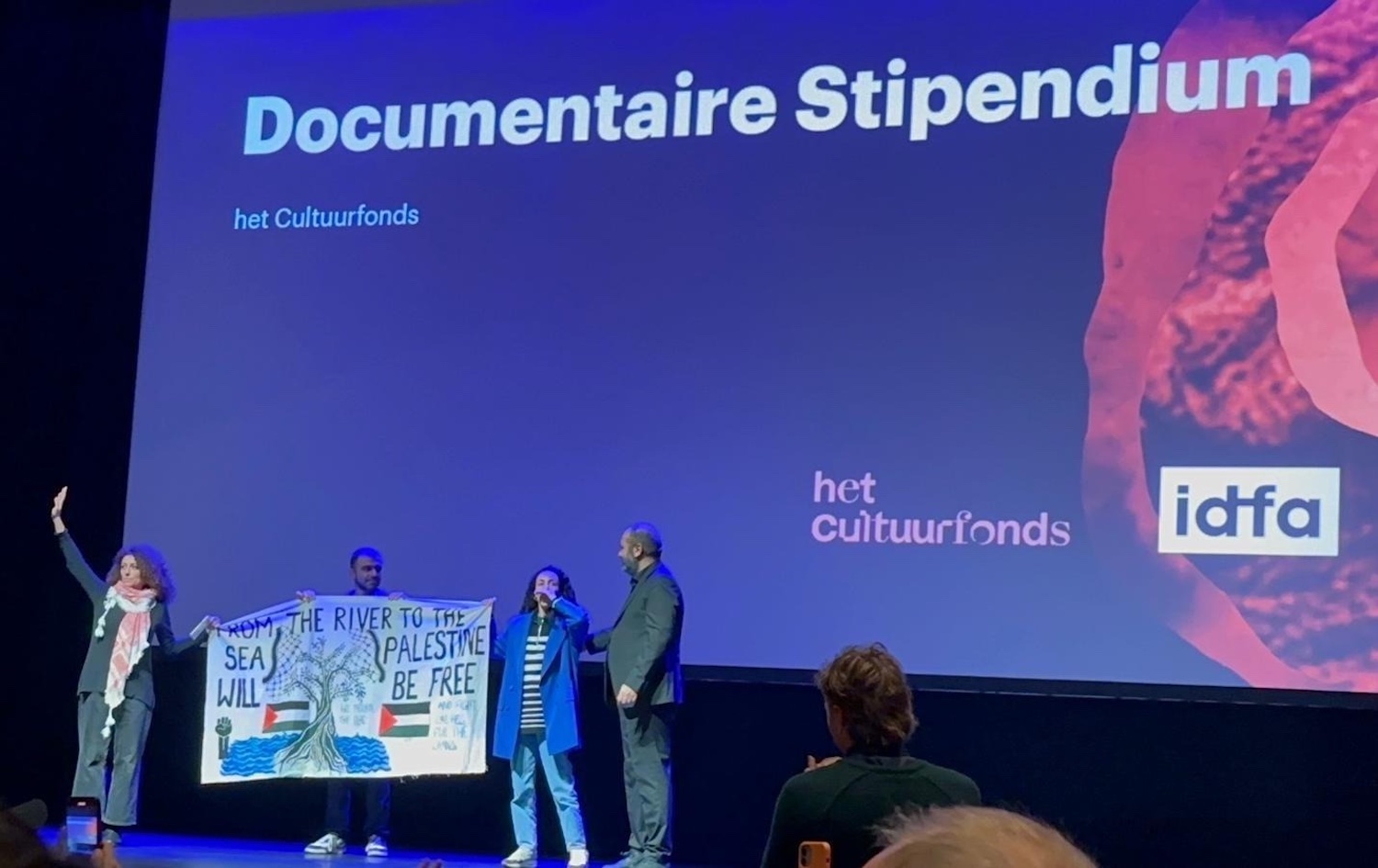

The festival started controversially during its opening night ceremony when pro-Palestinian supporters took control of the stage with a sign reading:

“From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free”.

It’s widely affirmed by activists, yet seemingly seldom heeded by those in institutional power, that this slogan is one of peace; described by recently censored United States Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib — crucially congress’ only member of Palestinian descent— as “an aspirational call for freedom, human rights, and peaceful coexistence.”

IDFA’s response, released two days later, was — unsurprisingly for an organisation that hadn’t taken any kind of stance up to this point — infuriatingly non-committal; a mish-mash of contradictory platitudes about the value of all human life, and a condemnation of the slogan itself. Despite acknowledging that there are many interpretations of the phrase, and ignoring that a vast majority understand its peaceful intent, IDFA was deliberate in condemning all of them. You know, just in case.

In these situations, it’s hard to know who to trust and who to believe, especially when arts institutions such as IDFA have been ingrained in the cultural consciousness as a meeting point of both international reach and progressive allyship. Harmful statements such as theirs, coupled with a subsequent defensive and empty call for a ceasefire in Gaza, erode trust built up carefully over decades.

While these events naturally diverted some of my attention away from regular festival film-watching, my interest remained in one of IDFA’s Focus programmes: Fabrications. An original mix of repertory films and new titles, as well a sprinkling of films from other sections, Focus: Fabrications took that almost cliché notion about the blurry lines between fact and fiction in documentary film, and offered up a programmatic space with almost as many interpretations as the films themselves. During one of the most urgent humanitarian crises in years — which has called into question the credibility of images of unspeakable violence disseminated on social media — one can’t help but approach these films and their relationship with the truth with renewed vigour.

Re-Make/Re-Model/Re-Construct

I was instantly intrigued by two films drawn from the Signed section: Marc Isaacs’ This Blessed Plot (2023, feature and above), a delightfully lo-fi, genuinely unclassifiable film charting a Chinese filmmaker’s trip to Thaxted in the English countryside, during which she’s introduced to a quirky cadre of locals and the ghost of the 20th-Century socialist vicar, Conrad Noel; and Jean-Gabriel Périot’s Facing Darkness (2023, below), in which filmmakers from Sarajevo revisit their wartime films from the early 1990s for the first time, in the very spots in which they were made.

In tone and subject matter, these two films couldn’t be any different, but they have an equally curious fascination with the camera. In both, the viewer witnesses a dual revelation of filmmaking, in which the camera is revealed as a tool of imagination and fabrication by the use of another camera. The effect is a fluctuation between critical perspectives, in which we see not only the films within the films, but also the films without the films. This meta approach pays dividends.

I wouldn’t say it signals the breakdown of the fourth wall; if anything, these films actively construct their fourth walls and periodically gaze at their subjects from around their edges — in Plot, as a child might wander unnoticed through a party of adults; and in Darkness as a scientist might observe an experiment.

In each, this detachment from constructed action represents and ignites the curiosity of both filmmaker and film-watcher, respectively. If documentary cinema is, either ideally or theoretically, some kind of pure exploration of the truth, these approaches, however seemingly paradoxical to traditional factual filmmaking they may be, make a lot of sense — their results are just as, if not more, affecting.

Fiction Meets Facts

The greatest pleasures and insights came from visiting past films I never had the chance to see — or had even heard of. Shirley Clarke’s “found-footage” masterpiece, The Connection (1961), had to be sacrificed in this instance; but two films new to me, Safi Faye’s Letter From My Village (1976, above) and David Schickele’s Bushman (1968), presented refreshing approaches to illuminating the divide (and intersection) between truth and fiction.

Letter From My Village was an understated discovery, a film of low-key tempos and gentle humour. Filmed in the director’s home village in Senegal, Letter functions as a kind of personal reportage on life under neo-colonialism, constructed like a mosaic of the village’s real inhabitants and their labour. The rainy season has abandoned them, the men are tired of growing groundnuts that deplete the soil of its nutrients, the women sing their way through their work, and taxes are too high (and so are the punishments for not paying, as we find out in a darkly humorous scene of childlike performance and exuberance).

All the while, the men of the village sit under a big tree discussing the old, pre-neo-colonial days. Threading this web of encounters and contexts is the courtship between Ngor and Coumba, two young people frustrated with the status quo, unable to marry until Ngor earns more money. While a move to Dakar proves alienating and often dehumanising, his return with just enough cash to marry lifts the film’s increasingly defeated spirit. All of these events are framed by a written letter, read aloud by Faye herself, allowing this sense of positivity to ring true and honest.

The second discovery was David Schickele’s Bushman, seemingly a more traditional narrative portrait of Gabriel, a young Nigerian man working as an assistant professor of African Studies at UC Berkeley, played by Paul Eyam Nzie Opokam. The film is propelled by a boisterous, late-60s energy, a frustrating decade of assassinations (an opening title card reminds us that Malcolm, Martin and Hutton are dead) clearly on the filmmaker’s mind.

This anger simmers underneath Gabriel’s laid-back personality, triggered, or more likely exacerbated, by a surreal encounter with a friendly but racist biker on the outskirts of San Francisco. There’s an American girl he’s having a fling with, but it probably won’t go anywhere, and his subsequent hookup with a well-meaning but oblivious white sociology student doesn’t help. Gabriel seems to find a more understanding community later in the film, with whom he goes to parties and camping trips. He even finds a meaningful romantic connection — but still, the anger lingers. He describes himself as a lion trapped in a cage in a zoo; you can give the lion food and water and things to do, but he still knows he’s in prison.

Bushman has all the hallmarks of narrative fiction filmmaking: the performances are lived in, but very clearly performances; the camera moves in ways that suggest prior planning, rather than the spontaneity of on-the-ground documentary. We break with this narrative structure only a few times; when Gabriel speaks about his experiences growing up in Nigeria, his contact with the Catholic church, the Peace Corps and other arms of colonial reach. These scenes play like a talking-head segment, but the casual, office-like setting complicates this — maybe he’s speaking to a colleague at the University, or perhaps a therapist?

Things fall apart when Paul, the real man playing Gabriel, is arrested on a phoney bomb possession charge and deported back to Nigeria, ironically, beating the filmmakers to their narrative punch. Schikele himself appears on screen, along with other members of the filmmaking team, in the most explicitly documentary-style section of the film. They say they actually had planned on filming a plotline in which Gabriel would get in trouble with the police and be deported. For a film directly injecting the real biographical substance of its leading actor and director into its fabricated reality, the invasion of the unexpected truth into their fiction is, perhaps paradoxically, less disruptive than you would expect. As Schikele said in his own talking head: “Truth was not stranger than fiction, just a little faster.”

Chris is an American freelance film programmer, writer, and critic based in London. He fills the rest of his time working in film distribution.