On September 4th, a call to boycott the New York Film Festival (NYFF) was shared on Instagram by a page labelled the New York Counter Film Festival (NYCFF). Chief among the reasons for the boycott was Film at Lincoln Center’s various board members with Zionist ties who provided financial support for Israel in recent years. The final straw was the announcement of Bloomberg Philanthropies, which has played a prominent role in supporting illegal Israeli settlements in the West Bank, as a Contributing Partner to NYFF.

This sponsorship spurred the efforts of radical film programmers and volunteers affiliated with local groups like cinemóvil nyc and Film Diary NYC to announce the NYCFF, running September 27 to October 10. In addition to dropping sponsorships from Bloomberg, the demands of the counter festival included Film at Lincoln Center calling for a ceasefire in Gaza, severing ties with other corporate sponsors like BNY Mellon, Bank of America and Citigroup for their financial support for weapons manufacturers directly arming Israel, and to end the relationship between FLC and the Consulate General of Israel in New York.

While these demands remain largely unfulfilled, the NYCFF’s programming showcased a rich array of work, several of which were withdrawn from NYFF, the Berlinale and IDFA. Reaching beyond Palestine, these films cumulatively mounted a clarion call for global solidarity, one emblematic of an abiding faith in the radical potentialities of the moving image.

One From the Art

Initially set to have its world premiere at NYFF, Rosalind Nashashibi’s The Invisible Worm (2024) first screened for the NYCFF at the eleventh hour. In the film, she foregrounds pleasure as the kindle to art. Its network of artists, professional or otherwise, who appear across the film’s fleet running time, demonstrate a collective method of disseminating the ideological underpinnings of cultural and political history through image-making — playful but never frivolous.

The central artist of the film, Elena Narbutaitė, addresses Nashashibi off-camera while skimming through fashion magazines. She’s taken by one male model whose taut posture is likened to that of the unseen artist fastidiously fussing over their work. The film reinforces these dialectical associations between artists and subjects, most whimsically in footage captured by Nashashibi’s pre-teen son Pietro, remarking on his mother’s influences between goofing off for the camera.

Nashashibi expands this intergenerational wrinkle to incorporate Benjamin Britten’s musical arrangement of William Blake’s The Sick Rose (1794). Britten’s composition, written during the Second World War, indicated a portent of calamity that Nashashibi vivifies through a stray hair caught in the camera gate, resembling Blake’s eponymous worm. The parting shot of this aberration towering over Westminster makes a fine point on Nashashibi’s latent political fury. By arriving at this grim conclusion through aleatory formalism, The Invisible Worm admirably positions its effervescent treatment of creativity as a fundamental riposte to hegemony.

Fishy Business

Niles Atallah’s Animalia Paradoxa (2024) similarly mines a haptic vein in its fixation on the bric-a-brac of a dying world. A post-apocalyptic fairy tale, the film’s nameless and amphibiously humanoid scavenger (Andrea Gómez) aimlessly sifts through the detritus of a derelict edifice. They encounter nightmarish figures, including a clawed hand in a wall beckoning for tributes and a shrill evangelical with an entourage of ghoulish fanatics, all the while dreaming of an ocean they long to return to.

Atallah’s association with the production team responsible for the Chilean stop-motion The Wolf House (2018, Cristóbal León, Joaquin Cociña) is indicative of his feature’s aesthetic emphasis on hand-spun decay. The cinematic progenitors evoked by this aesthetic are numerous, but Atallah’s prevailing focus on physicality and fluidity (literal or gendered) gives the film its political potency.

Indeed, Atallah’s politically inverted spin on H.C. Andersen’s The Little Mermaid (1837) shines when it accentuates Gómez’s acrobatic performance which enfolds traces of Buster Keaton and Lee Kang-sheng. These ghosts of cinema, in Atallah’s eyes the most febrile of physical artists, inundate the haunted house of a disturbing future. Yet Animalia Paradoxa does harbour some hope, if not for mankind then for the physical traces of our creative pursuits, chief among those the moving image.

Perchance to Dream

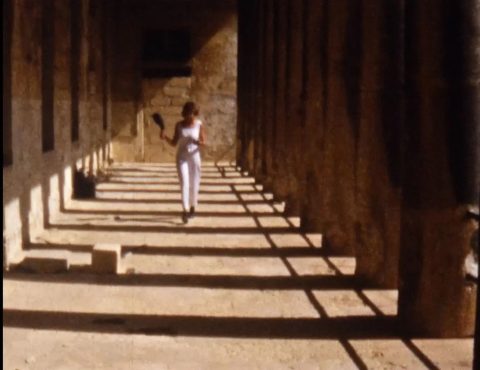

Eschewing any semblance of narrative altogether, Basma Alsharif’s Deep Sleep (2014, feature image) induces the viewer into a trance state across three cities. Shot in brashly warm celluloid, the film’s snapshots of Athens, Gaza and Malta reject an exoticised treatment of these sites. Rather, an emphasis on bilocation spurs contemplation after the fact on the psychic geography mapped out for an absent homeland.

Alsharif shot the film in a trance state, and her roving camera accordingly lacks a strictly prescribed methodology. Handheld pans through foliage or lingering shots of a blue sky heighten the organic quality of these visions with the film’s grainy textures. Whenever Alsharif extends a pointed finger to an ancient structure, the very material of the film is overwhelmed by emulsions and sonic incursions, such as the peal of bells.

The significance of recurring motifs like the bells or a black horse is suggestive rather than instructive. But as the film’s experimental flourishes proliferate, Alsharif’s intentions become clearer without resorting to didacticism. When the bells peal in reverse, commensurate with the horse’s backward movements, Deep Sleep reveals a yearning for a return to a past preceding displacement and exile. The final moments provide no clear solution to this urgent quandary, but its serenity is no less charged with political verve and resilient grace.

Seeds of Change

Jumana Manna’s documentary feature also traverses three different points of geographical interest, albeit with its feet firmly in the waking world. Wild Relatives (2018) observes the joint efforts of workers in Lebanon, Syria and Norway towards sustainable agriculture. Manna’s crosscutting between the film’s locales provides fleeting glimpses into the lives of her subjects as participants in an urgent transnational project.

While climate catastrophe and warfare dances around the edges, Wild Relatives opts for a surprisingly tranquil tone. Wide shots of labourers harvesting fields for seeds contain plenty of naturalist poeticism, and it’s indeed this focus on collective labour that provides the film its strongest throughline. The Global Seed Vault in Svalbard presents the scientific ideal of these efforts; rows of rare seeds collected in its archives succinctly speak to another iteration of this ideal.

The conversations we glean from the human figures are largely banal, ranging from liaisons with ICARDA to commiserations over smoking cigarettes while working the fields. Yet the quotidian glimpses culminate in a frank conversation between a man and a priest outside of Longyearbyen on the borrowed time of the human race. “I believe in humans,” the priest insists. So does Manna. The largely unvarnished humanism of her patient filmmaking gives this maxim a poignant urgency.

Nick Kouhi is a programmer and critic based in Minneapolis, Minnesota