Miko Revereza’s filmmaking repudiates borders.

As an undocumented Filipino immigrant granted tenuous protection under DACA, Revereza uses digital media to interrogate and blend the temporal and spatial boundaries which have informed his familial lineage and shaped his sociopolitical identity. Revereza’s polymorphous form of diaristic documentary makes his films deliberately expansive and unruly. With his new feature Nowhere Near (2023), he builds upon his earlier work to mount an ambitious return to a homeland he may no longer recognise.

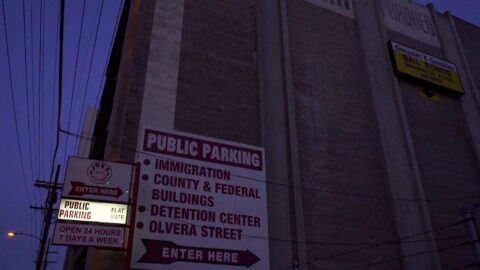

Revereza, who has lived in the United States since he was five years old, has defined this film as his version of a “Great American Indictment”. This grandiose description stems from the bureaucratic indifference which has wrought psychological violence on him and his family. Childhood polaroids of Revereza with his parents are marred by their missing heads, cut out for use in their passports. In 2017, when this project began to take shape, scant employment opportunities prompt Revereza’s mother to relocate from Los Angeles to Minnesota. When told she’s procured her job through an old friend from Catholic school, Revereza quips:

“When was the last time you met a charitable Filipino from Catholic School?”

A brief portion of Nowhere Near has the filmmaker visit his mother in the Twin Cities (Minneapolis–Saint Paul) His first stop is the Mall of America, where he absorbs the spectacle of the Nickelodeon Universe amusement park. As someone from Minneapolis, viewing my hometown through Reserveza’s eyes yielded a particular poignancy. His camera captures a hermetic quality inscribed in the concrete tunnels that connect indoor malls and parks throughout downtown. More than a uniquely Midwestern trait (though it’s also certainly that), Reserveza aptly identifies how these spaces perpetuate implicitly threatening social hierarchies for immigrants like themselves.

The perpetual fear of deportation and the alienation this fear foments is rooted in a multi-generational, jingoistic fervour. Nowhere Near links the bombing of Afghanistan following 9/11 and the U.S. invasion of the Japanese-occupied Philippines during the Second World War; observing with steady rage how imperialism has affected Reserveza’s family across three generations. But the film harkens back even further to his Lola’s (grandmother’s) grandfather, who was the Gobernadorcillo of his municipality during Spanish colonial rule. It’s a wrinkle that complicates a historical narrative devoid of complicity within colonial projects.

Revereza revisits this thread in the third act, yet he’s more interested in an interpersonal connection between a long-dead relative and his Lola than a politically contested one. She has her own motives for returning to her hometown of Pangasinan, initially viewed through a set of landmarks and routes on Google Maps. When she and Miko visit the town in person, she can only ruefully allude to its former grandeur. Cultural memory, and its formation through media, has been a recurring thematic strategy in Revereza’s work. His shrewd extrapolation of transnational reverberations within images culled from movies ascribes to a Godardian notion of criticism as its own filmmaking practice. A particularly incisive example is an extended reading of Miyazaki’s Spirited Away (2001) as a parable of a migrant child forced into exploitative labour.

Nowhere Near announces this multidisciplinary ambition at the start by citing the Chilean exile and writer Roberto Bolaño (also referenced at the start of this year’s Venice title, Foremost by Night (Víctor Iriarte, 2023)). If Bolaño’s fiction sought to reconstruct a transnational narrative for the 20th Century, Reserveza’s intensely personal nonfiction hones in on the past’s production of a residual, psychic turmoil. Two sequences, prominently consisting of transitory images, are scored to Reserveza squealing into a clarinet, softly swearing to himself. These moments indicate an attempt to exorcise the powerlessness calcified by systemic negligence as the current of history rapidly roils onward. As Revereza notes, the syntactic tools for articulating this condition are invariably shaped by political hegemony — as is the case with Tagalog integrating Spanish and English words into a “loan language.” The question posed, then, is how a new language can be forged; namely, one which dispels the weight of a colonialist past without effacing the memory of those imbricated within it.

Revereza ruminates upon this unresolved dilemma while images of a stream carrying “migratory bubbles” course throughout the film. This motif overlaps images of intimacy and remembrance, and it ultimately serves to guide Reserveza out of the film as he struggles with his growing detachment from the project and a homeland he must bid farewell to. Where his movement away from diaristic documentation will take Reserveza remains to be seen, and his attempt to meld self-actualisation with a reckoning of inherited trauma may not combine his formal and thematic designs to wholly legible ends. But if we’re left with a processual rather than enclosed text, its intimations powerfully signal how Reserveza is beginning to mould the burden of history into a radically moving present tense.

Nick Kouhi is a programmer and critic based in Minneapolis, Minnesota