Masturbation with instructions — that’s what The Male Gaze Recipe (Alma Weber, Joey Arand, 2024), the opening short, is about. After this subversive cooking recipe, Michael Vorfeld presents a 16mm performance of pure pattern and movement.

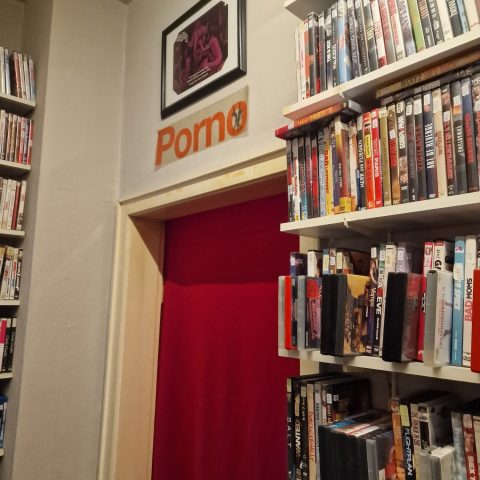

The Randfilmfest, taking place this year in Kassel between 26 to 29 September, provides a welcome sanctuary for such obscure and repressed works that one (in proper English) once called “Video Nasties”. It’s held at the Bali-Kino inside Kassel Central Station and the Kiez-Kino — a backroom of the Film-Shop, the world’s oldest video rental store.

A Film-Shop employee guides me through the impressive film collection, followed by the VHS-porn area hidden behind a classic red curtain. The walls appear to be made of film. The location belongs to Randfilm e.V., the parent organisation of the festival, where screenings, events and other odes to lost media take place. Tickets are scanned at a leisurely pace. While the organisation may be a bit rough around the edges, it adds a certain charm. Not enough seats in the cinema? More are quickly added.

Collateral Damage and Queer Aliens

The ambition of the festival is best described by the opening-night film Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1975). Not dug up simply for its shock value, but as part of the Collateral Damage section, a study of the irreversible impacts of war. In contrast, the Fantastic Queer Connections section offers a colourful celebration of the outskirts, not just on screen but in our cultural spaces. The outstanding Liquid Sky (Slava Tsukerman, 1982, above) about queer, heroin-addicted, draped-in-David-Bowie-esque-garb, New York-punk-scene-invading-aliens, is campy while dense in discourse.

Pictures Come And Break Your Heart

Bruce LaBruce’s satirical adaptation of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s classic Teorema (1968) — renamed The Visitor (2024, above, reviewed previously) — is a perverted take on bourgeois Marxist critique turned into fetish porn. A mysterious visitor, washed ashore in England in a suitcase, subverts racist prejudices and turns sexual repression into liberation. Actor Bishop Black infiltrates a family, dismantling each member’s ideological delusions. The Visitor found a perfect home at Randfilmfest. While no scandal erupted at its premiere at Berlinale, there was tension in the air during the projection of this chamber sex play.

“Is it okay to leave now?”

“Would walking out seem homophobic?”

Faces of the industry representatives screamed. A Randfilmfest attendee, on the other hand, made an interesting observation: Salò shocked him more, as it was “so aesthetically unaesthetic,” while The Visitor almost gave him “too much fun.” People are connecting the dots and ideas grow — a curational success.

L’Empire (Bruno Dumont, 2024) and Divinity (Eddie Alcazar, 2023) stumble when trying to fully break their genre boundaries, as The Visitor did. L’Empire (either loved or hated since its premiere at Berlinale) is a Star Wars-fanfiction-lightsaber-good-vs-evil-small-town-drama. Its light-hearted apocalypse doesn’t quite hit the intended tone. Similarly, the retro-obsessed Divinity fuses so many genre clichés that little remains beyond sheer aesthetics. All three films manage to break our genre-loving hearts in their own way, and aim to shock us with images.

A Bomb Under the Table

Oddity (Damian McCarthy, 2024, above) is perhaps the most classic horror film in the program, appealing to a Fantasy-Filmfest-type audience. The film masterfully builds suspense in line with Hitchcock’s famous bomb-under-the-table maxim. Oddity places its monster in the protagonists’ dining room — and leaves it there. The film plays with sound and image, tricking us into doubting our senses. It ultimately proves that human violence is far more terrifying than any ghost.

Best Wishes To All (Yuta Shimotsu, 2023), on the other hand, exemplifies what is now called “horror as a vehicle”. Based on a home invasion that has already taken place, the film reflects on generational guilt, social norms, and their violent acclimatisation. The film uses metaphors related to veganism, environmental destruction and other issues that today’s children inherit from their parents. The uncanny tilt into a world in which the immoral is enforced becomes the ticking bomb under the pictures, the explosion of which we tensely await.

The Obscure Form

She Is Conann (Bertrand Mandico, 2023) and Makamisa (Khavn, 2024) were the most stylistically daring films of the festival. The New York Times described She Is Conann as a “feminist riff on Conan the Barbarian (…) sprinkled with a bit of glam-rock fairy dust” — a fitting description. Director Mandico finds radical images to transform an old tale into a feminist odyssey. In stark contrast, Khavn’s Makamisa shows us more colours than our eyes can process. Shot on expired film and later hand-coloured in his bathtub, this avant-garde silent tells an almost incomprehensible story in formal brilliance.

What Does Madness Sound Like?

The highlight in Kassel was the festival-commissioned live scoring of the Japanese silent classic A Page of Madness (Teinosuke Kinugasa, 1926, above), performed by Frauke Aulbert and Michael Vorfeld. Drawing from its predecessors like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Robert Wiene, 1920), Nosferatu (F.W. Murnau, 1922) and Häxan (Benjamin Christensen, 1924), the film explores the ambiguities between masks, faces and whatever lies beneath. Later observations about such topics in films like The Face of Another (Hiroshi Teshigahara, 1966) Onibaba (Shindō Kaneto, 1964) or even Eyes Without A Face (Georges Franju, 1960) can already be found here. The live score, oscillating between hints of traditional Japanese music and pure avant-garde noise, captured the psychotic images perfectly.

So What?

A line that appears both in L’Empire and in Liquid Sky encapsulates the unapologetic attitude of the festival: a sassy “So what?” The Randfilmfest isn’t defiant; films aren’t celebrated because they were banned, but rather despite it. Well, maybe a little. After all, the unseen does carry a somewhat Walter Benjaminian aura of rarity.

A used book, found in a box in the Film-Shop waiting to be discovered, offers the best description of the Randfilmfest as a whole: Amos Vogel’s Cinema Defying Taboos! (Film as a Subversive Art) (1974), a manifesto of subversion and morally-restricted art.

On the festival’s website, another Vogel quote greets you: “Subversion in cinema starts when the theatre darkens and the screen lights up!” Certainly an imperative against those who have long declared cinema dead. I leave Kassel with mixed feelings — on the one hand, pure euphoria for the fringe film culture that has found a home in Kassel; on the other, heartache when seeing empty seats. At Randfilmfest, what was said to be dead returns on the screen.

Niklas Michels is a film critic and curator who, in addition to his film work, researches the space between ethics and aesthetics at RWTH Aachen University.