True/False showcases international documentaries that fuse aesthetic experimentation with thematic timeliness. This year’s features and shorts span the globe, profiling collectives and individuals who use art as a launching pad for preserving diverse narratives which implicitly contravene the homogenisation of cultural history.

The films I saw in my first True/False embodied these characteristics in their explorations of polyvalent relationships between past and present, nature and urbanism, with desired aims to educate and entertain in equal measure.

The Eternal Everglades

A venerated conservationist provides the framework for River of Grass (2025), an expansive, visually confident feature from Sasha Wortzel. Elegantly fusing subjective and sociological histories of the Everglades11.5 million-acre wetlands preserve in Florida, the film’s abundance of striking imagery effectively complements Marjory Stoneman Douglas’ pastoral prose.

Wortzel provides an overview of Douglas’ life, from her first trip to the Everglades at four years old to her lifelong advocacy as an environmentalist protecting it from unregulated development. Yet the film subversively eschews hagiography to highlight contemporary figures in the fight against climate change, most notably Miccosukee2Native American educator Betty Osceola.

In its proliferation of various voices, River of Grass mounts a dialogue on memory mediated through ecology. It’s a dialectic traced with political dimensions, and the film’s blending of archival footage with kinetic wildlife imagery showcases a sophisticated understanding of the dynamic interplay between past and present. “Water has life, it has memory,” Osceola remarks, and it’s a philosophy shared by Wortzel, a Florida native who recounts school trips through seas of sawgrass.

Viewers hoping for a deeper exploration of Douglas — who makes for a candidly pragmatic purveyor of the 20th Century — and her life will doubtless be disappointed by the film’s mythic treatment of her legacy. Indeed, River of Grass frequently foregrounds humans against their environment, imploring some humility on the part of a society whose intelligence Douglas held little faith in. In that vein, the film’s pedagogical aims are imbricated within an ethos of accepting the limitations of activism in a frighteningly industrialising world.

That said, Wortzel denounces pessimism through her formal eclecticism. Like Terence Malick, she understands the camera’s potential for reconfiguring our perception of the natural world towards gratitude and resolve rather than despair.

The Life Aquatic with Eleanor Mortimer

A crew of marine taxonomists plumb the ocean floor for undiscovered life in How Deep Is Your Love (2025). Eleanor Mortimer’s winsome exploration of the life aquatic yields plenty of wondrous sights, all in service to an ostensibly noble project to protect uncharted terrain from invasive mining. While dazzling, the film’s tranquillity courts thematic inertia, lacking the formal audacity or political wit of a documentarian like Jean Painleve.

As Sasha Wortzel did for River of Grass, Mortimer provides offscreen narration, her lilting cadence gently chronicling her travels with a 54-person team disembarking from Puerto Caldera, Costa Rica to the Clarion-Clipperton fracture zone in the Pacific Ocean. The area the team is surveying, first captured on film in 1979, hosts myriad animals as well as valuable minerals first trawled by the HMS Challenger in 1873. In this century, the International Seabed Authority in Kingston, Jamaica, convenes in its latest session with a delegation of national ambassadors to deliberate on the excavation of Manganese-Iron modules.

Mortimer isn’t permitted to record the meetings, but what questions she’s allowed to pose include what sea animal the attendees would like to be. This lightness of touch extends to the film’s treatment of the crew, and while their personalities are discernible they remain kept at a distance. While Mortimer’s attempt to portray her human subjects with the degree of detachment they hold for their oceanic discoveries is a clever conceit, it remains undercooked.

What interest or enthusiasm the film harbours for its myriad wonders is hardly enough to overcome its episodic structure or allegorical obviousness in its climactic superimposition of sea creatures onto landlocked, man-made spaces. Nevertheless, by dint of their sheer inimitability, the animals that give How Deep Is Your Love its raison d’être makes Mortimer’s earnestly flawed flourishes more palatable.

The Mance Behind the Music

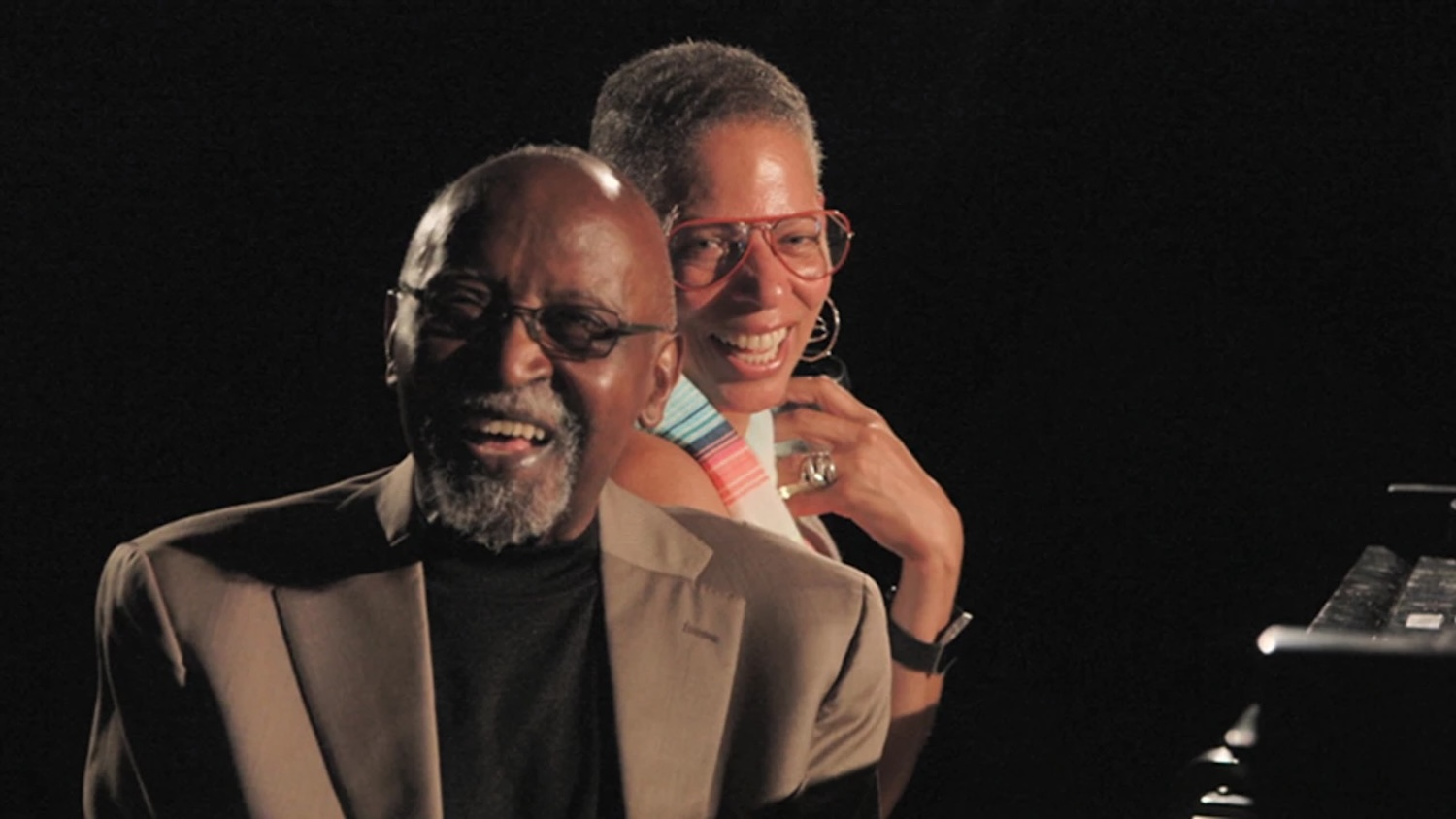

The legacy of another creative titan from the preceding century is assayed through a personal lens in Sunset and the Mockingbird (2025). Jyllian Gunther’s portrait of Gloria Mance, widow of jazz pianist Junior Mance, condenses a professional and romantic partnership that lasted thirty years into thirty minutes. With swift economy, Gunther’s short is a modest, ably crafted tribute to the muse behind the artist.

Gloria and Junior’s final months together give the film its narrative thrust and emotional throughline, peppered with archival performances by Junior. The thrill of seeing Mance perform alongside Dizzy Gillespie is treated with plainspoken candour, a mythic footnote in the quotidian challenges Junior faces following a stroke that has instigated dementia. Gloria, who has been Junior’s manager since they first met in the early 90s, grapples with the unassailable fact that her husband will no longer be able to perform the craft he’s mastered.

Gunther’s crosscutting between Junior’s past and Gloria’s present is the film’s strongest asset, succinctly illustrating the relationship between art and its purveyors. This dynamic is explicitly stated by Gloria in relation to the song that gives the film its title: “I’m the mockingbird to keep his legacy alive. And he’s the sunset.” Sunset and the Mockingbird privileges Gloria’s perspective, including narrated diary entries of her grief and acceptance of the limited time she and Junior have left together.

Because of the film’s humble scope, Junior’s placement in the pantheon of American jazz giants is granted secondary importance. While a broader assessment of the genre and its sociopolitical value is missed, Gunther’s film is nevertheless moving for its intimate valorisation of those who strive to preserve its memory.

Nick Kouhi is a programmer and critic based in Minneapolis, Minnesota