On the Lido, half an hour boat ride from Venice proper, cinema has a natural adversary — the beach.

Yet this idyllic setting remains surprisingly empty, while cinemas overflow. Tickets are in high demand; last-minute attempts to catch a film usually fail. At 33 degrees, with four euro Aperol Spritzes and too-long queues at the gelato stand, it’s only a minute’s walk to the next screening. That’s Venice.

Just as the festival floats liminally between laid-back Berlinale and posh Cannes, so too does its programme oscillate between Oscar-bait and arthouse cinema. While one misses the avant-garde and underground films that find a home in Berlinale’s Forum, on the other hand, the Venice Film Festival regularly prides itself on premiering future Oscar winners.

The competition is crowded. Predictions about possible winners are diverse. Let’s have a look at the candidates.

Big Screens, Big Stories

The competition marks a return to grand storytelling — epics, sagas, genre staples. Justin Kurzel, who already brought amok to the screen with Nitram (2021), switches to terror. The Order (2024, above) portrays the true story of a radical alt-right group inspired by the propaganda book The Turner Diaries (William Luther Pierce, 1978). His film moralises violence on the one side and aestheticises it on the other. Sparks fly between FBI agent (Jude Law) and Nazi (Nicholas Hoult). They hate each other, but love to do so.

Brady Corbet’s Silver-Lion winning The Brutalist (2024), is three and a half hours of grandeur; the story of the fictional Jewish architect László Toth and his immigration to America, transforming his Bauhaus buildings into monuments that match the scope of the film itself. The Brutalist follows in the footsteps of works like The Pianist (Roman Polanski, 2002) and There Will Be Blood (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2007) as it makes Toth’s life — a cautionary tale — object to its critique of capitalism.

And, when talking about grand stories, one would have to mention Joker: Folie à Deux (Todd Phillips, 2024) This completely unnecessary sequel stalls so much that it can hardly be called a story. Compared to the films mentioned above, Joker: Folie à Deux feels like a chamber play.

Age, Sex And Other Patriarchal Monsters

Maria (Pablo Larraín, 2024) and Babygirl (Halina Reijn, 2024) negotiate ageing and decay in diametrically opposed ways. Angelina Jolie (in Maria) and Nicole Kidman (in Babygirl) become bodies whose bloom seems to have passed, whose gazes are fixed on the past. The daily habitus becomes a means of maintaining a faded beauty, which represents power in Babygirl and sublimity in Maria. For the first time, Pablo Larraín manages to free himself from his aesthetic obsession and paints more than just nostalgia on the screen. His biopic travels through a lived life, whose last sparks are fading. While Babygirl aims to be radical and provocative, the oversexualised images pale against Larraín’s requiem.

The biggest surprise was Dea Kulumbegashvili’s slow-cinema creature film April (2024, above). At first, critics spoke of this Georgian film as a potential winner in whispers. Suddenly, it was considered a favourite. Kulumbegashvili stages a protest in April weather — a film of silence and unspoken words. An ominous monster in gloomy landscapes becomes emancipation as background noise. The film conjures directors like Chantal Akerman, Angela Schanelec, Urszula Antoniak. The barely visible shifts in reality, with a touch of The Piano Teacher (Michael Haneke, 2001), result in a powerful collage of female trauma, homing around the topic of abortion. It receives the Special Jury Prize, a well-deserved nod to a film that, in its bold form, would have been too heavy to capture the main award.

The Winner Next Door

Golden-Lion winning The Room Next Door (2024) is Pedro Almodóvar’s first English-spoken feature film. He casts Tilda Swinton, who under his direction — even more than usual — becomes a ghost among the living. The Spanish director shows cracks in the everyday, his magical realism a cinema of invisible transformations; right before our eyes, yet still elusive. Swinton’s character wants to end her life. Against loneliness, she asks a friend to accompany her. A pill, a door that will open or close and a room next door transcend Almadovar’s melodrama into a metaphorical experiment whose inconspicuous execution asks the question of questions:

“What is the good life?”

The End of the World (As We Know It), or Venice’s Orizzonti Section

Orizzonti encompasses a smaller competition, where films are freer in form and more political in content. Among the sizable grey mass of classic festival films, some stand out (for better or worse). Take 2073 (2024) by Asif Kapadia, which sends the audience a time capsule from the future through a dystopian narrative and real footage. Trump, Elon Musk, social media, war and destruction become high-frequency cinematic doom-scrolling. A truly tasteless film, which in its form reproduces exactly what it attempts to criticise. The director of the genius deconstruction of Amy Winehouse’s life Amy (2015), does not understand the complex matter through which he pretends to move freely.

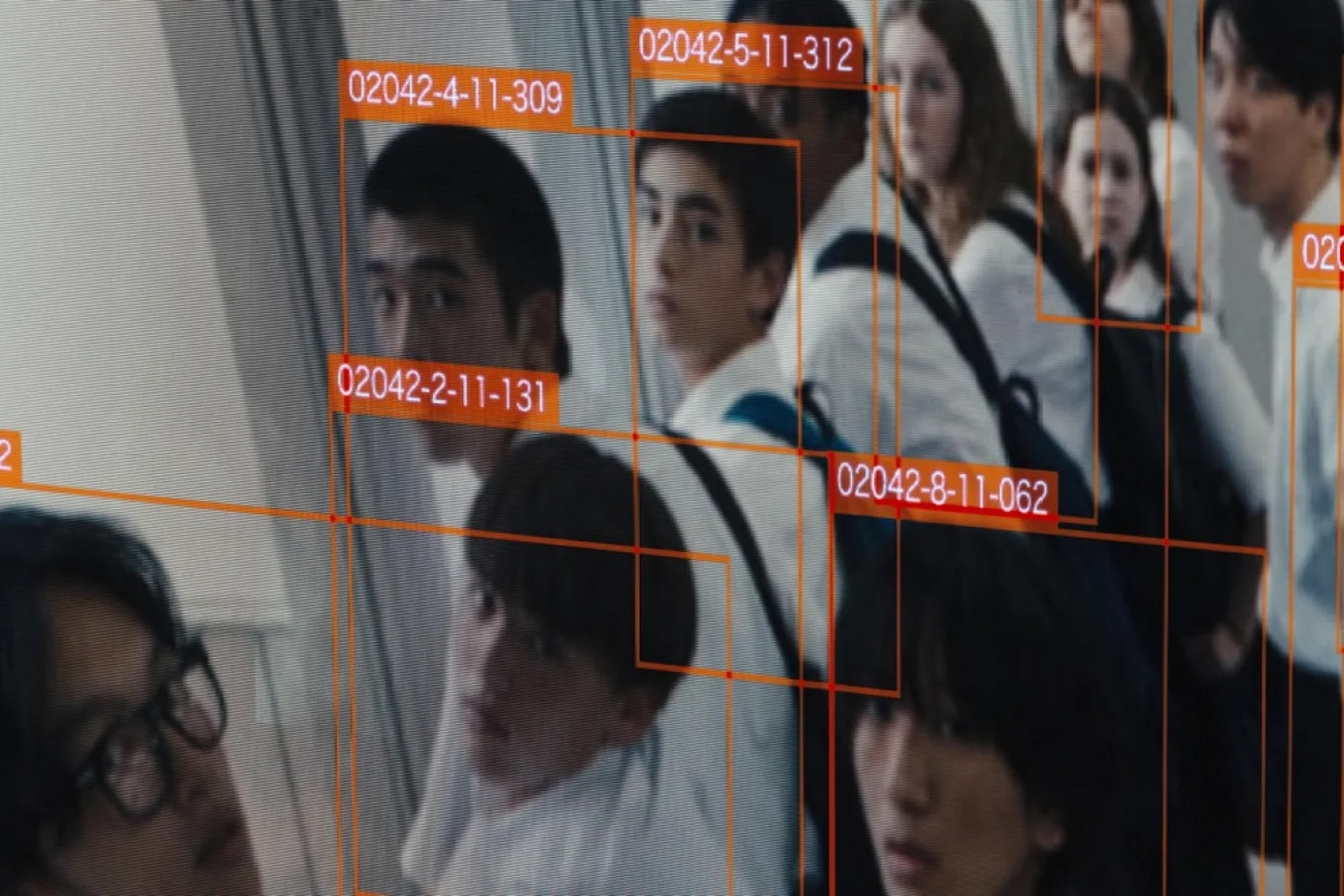

Neo Sora, the son of film composer Ryuichi Sakamoto, presents Happyend (2024, above), his first standalone feature film (not about his father). A firework of ideas, blending classical and electronic music, with a structure that could easily be one of the strongest at the festival. In a not-too-distant future, in an ethnically diverse Japan, a school implements an AI system that mimics China’s social credit score. A student protest follows. Sora manages to turn the protest into a template, breaking down Marxist opposition.

2073 and Happyend contrast, showing how important a film’s ideological integrity is to its identity. Two films with the same intention, yet their respective quality flickers on screen like night and day.

What remains of Venice is the oxymoratic difference between boiling heat and gloomy cinema. Between the sun outside and the rain inside one wanders their days through Lido. While big names like Joker 2 and Beetlejuice Beetlejuice (Tim Burton, 2024) try to outshine, we are with Almodóvar in the room next door, off the track, looking at films full of contradictory encounters, and a win for auteur cinema.

Niklas Michels is a film critic and curator who, in addition to his film work, researches the space between ethics and aesthetics at RWTH Aachen University.