Rarely has the unsayable spoken so loudly as in White Lies (2025), Alba Zari’s extraordinary documentary about the lingering effects of surviving a cult on an Italian family. Where other films would frantically fill in the absences with platitudes or pat resolutions, this deeply intimate portrait is happy to embrace the unknowable — and is all the richer for it.

Alba Zari was born in Thailand among the Children of Cult sect, although she has precious few memories of her time there. Her mother, Ivana, and Alba’s grandmother, left to return to Italy when she was just a small girl. She doesn’t know who her father is either; her mother took part in the infamous Flirty Fishing practice, whereby women would seduce and sleep with strangers to spread the word of the lord. While fornication was OK, protection was not, leading to Alba’s birth to an unknown man.

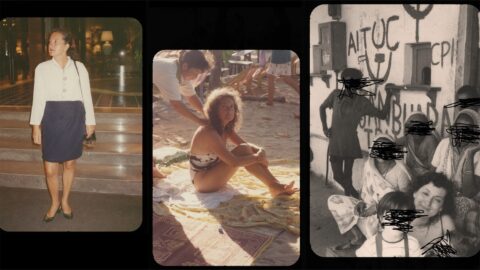

Instead, Alba thought that her father was the enigmatic Johnny, who remains in the sect in Thailand, while her family are split between Trieste and Positano. Desperate for answers, and driven to find out who her true father is, she takes two paths: a journey back into the archives, and contemporary footage interviewing her mother, uncle and grandmother.

Film images and video footage of Ivana and her mother among the streets of Bangkok and beaches of Phuket are deliberately contrasted with Zari’s precise use of voiceover, explaining the insidious practices of Children of God, infamous for their “free love” approach, which, like in many cults, was a euphemism for a culture of sexual abuse, including of children.1It’s particularly sickening to learn that the Children of God sect — now known as The Family International, and which counts Rose McGowan and Joaquin Phoenix among its former members — is still functioning, as shown in a brief scene where Alba visits Johnny back in Thailand. I find it especially galling not because adults are choosing to join such practices, but because they bring their children along with them, even though they are exposing them to a lifetime of pain.

Eager to collapse the past and present together, as if to create a bridge, Zari recreates shots, such as behind-the-shoulder takes of the women by the sea, and contrasts them together. And in one particularly effective combination, a widescreen modern-day image of Zari swimming is then adjusted to 4:3 before cutting back to video footage while still overlaying the original image. The effect is both striking and chilling — suggesting waves of trauma reverberating throughout the generations.

Yet a far more significant part of the film involves Zari quietly questioning her family asking simple yet direct questions in the hope of clarification and catharsis. The film shines in these moments of stunning vulnerability, as much as in what her family members can’t say as what they can.

Eventually, the family all gets together. In the fictional version of the story, one could imagine fireworks and angry accusations, but that doesn’t quite happen here. The difficulties of the past are raised, but then not quite finished, leaving behind a sad feeling of unresolved tension. Throughout the film, Zari doesn’t expect to find all the answers to how her life has been shaped by these malevolent forces, calling the film a mosaic of fragments instead. What’s remarkable is that I didn’t feel short-changed by the lack of clarity. If anything, it speaks to a true filmmaking integrity; welcoming the gaps and using them to instil the film with a powerful sense of melancholy.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.