History is of no small consequence, least of all to longstanding institutions.

The Berlinale’s Forum programme, independently curated by the Arsenal Institute for Film and Video Art, is already over half a century old, and encompasses a sizable portion of the festival’s history. It’s fitting, then, that the handful of films I saw from this year’s selection probe the ways history, ever contested, is inscribed onto the future. From traditional documentaries to more unorthodox modes of reflection, the highlighted filmmakers often interpolate their personal stakes upon the subjects they depict — in ways both oblique and direct.

An African-American Ghost Town

Direct address occurs a little over halfway through ALLENSWORTH (2022, above), James Benning’s latest exercise in ethnography that explores the hauntological traces inscribed in a ghost town. It comes in the form of a teenage girl named Faith Johnson reciting from a book of poetry. She never lifts her eyes from the words written by Lucille Clifton, casting her gaze away from the invasive eye of the camera lens. Yet if there’s any shyness or fear in this young woman, she shows none of it as she retains the steadfast proclamations of Clifton’s combative exhortations against the racial sins of America. All this historical and cultural weight is confined to the present moment: a performance devoid of performativity.

Allensworth isn’t just any sleepy outpost. It was the first town in California to be founded and governed by Black Americans. A title card indicates 1908 as the year of its founding — Benning’s regionalist portrait was filmed well over a century later. In twelve discrete shots, the film surveys places of historical import, unified by a common, angular architecture of dust-kissed buildings largely empty of human activity. Any vestige of the pioneer spirit which established the town is supplanted by the steady din of the freeway or a caravan of train cars carting cargo toward destinations unknown.

Benning’s final shot of a cemetery sparsely dotted with wooden crosses planted over the graves of those lost to history consigns, at first blush, the town to the status of an outdoor mausoleum. Yet relegating history to the past tense would be antithetical to Benning’s minimalist evocation of time’s passage. The subtlest temporal indications, from the parting of clouds to leaves dancing in a violent breeze, contrast with rare intrusions of the past in the form of non-diegetic song cues. By pairing, in one instance, Nina Simone’s “Blackbird” against a shot of the First Baptist Church, Benning’s emphasis on the psychic spectres haunting a site of communal mourning makes clear the political dimensions which shape the aesthetics of a community; touchingly honoured in his concise, potent tribute.

The Private Body in a Public Institution

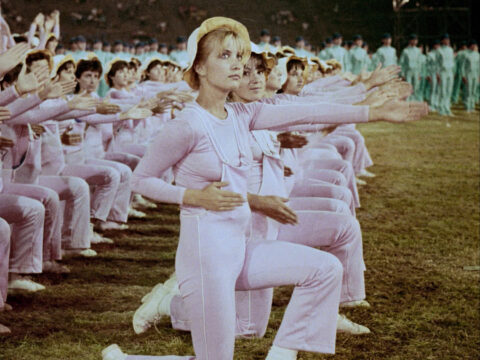

By contrast, the observational cinema of Claire Simon is in no shortage of human figures. Our Body (2023, above) extends the French documentarian’s corpus into the sphere of medical caregivers providing treatment to female patients. Simon has proven herself a master in pinpointing the minutiae of human behaviour within the confines of public institutions. Like Frederick Wiseman, her attentive camera captures the tiniest gestures of anxiety, frustration and even joy as the myriad women who visit the hospital contend with pregnancy, gender transition and often their own mortality.

This final point introduces an intriguing wrinkle, complicating any facile comparison to Wiseman, when Simon turns the camera on herself as she receives troubling news from the physicians. This development occurs late, when we’ve already witnessed numerous consultations between doctors and patients hailing from a diverse socio-ethnic background. Simon’s humility doesn’t allow her own narrative to supersede those of her subjects, some of whom recognise her from her prior work. While occasionally asking them questions, she’s too smart a filmmaker to project her own experience onto those of other women.

Those experiences form a mosaic which is profoundly political, though the stakes vary for each woman. Several patients are first-generation, predominantly working-class, immigrants whose political stakes in their body are complicated by both social and linguistic barriers. A particularly poignant scene where a Filipino woman is given terrible news through an internet translator reifies the tenuous aid technology provides in place of societal support systems. When a throng of protesters gathered outside the hospital speak to recurring malpractice and sexual assault from their purported caregivers, the film’s compassion is underscored by a pointed social critique refreshingly lacking in didacticism.

Epistolary Epiphanies

Less subtle, though no less powerful, is Vlad Petri’s Between Revolutions (2023, feature and above). Drawing upon a trove of archival footage, the film presents a correspondence between two women: Maria, a Romanian university student aiming to become a nurse, and her colleague Zahra, who left Bucharest in 1978 to return to Iran. The tone of Zahra’s letters, initially exuberant at the seismic changes taking place in her country, gradually shifts to despair and fear as the installation of the Islamic Republic sparks a crackdown on intellectuals and leftists — including her father. Maria’s fate fares no better as she first struggles with working post-graduation in a small town, before returning to parents coercing her into marrying an emotionally remote man.

The letters spoken in voiceover narration are revealed to be an amalgam of words, written by multiple women, confiscated by the Romanian Secret Police. Petri’s form of critical fabulation vivifies two women who share a common role within a relentlessly surveillant patriarchal society. Positioning his heroines as ultimately helpless in combating the socio-historical factors guiding their paths is a familiar trajectory. This threatens to simplify the film’s assemblage of footage detailing resistance and adaptation toward new political regimes. By contrast, a climactic moment in Notre Corps where a patient understands her imminent passing avoids sentimentality while emphasising an unflappable and deeply moving dignity. Between Revolutions lacks that complex paradox of powerlessness and agency, even if its formal structure contains invaluable footage of those actively shaping — for better and worse — their social history.

What Happens after The End of History?

But what of the end of history, to paraphrase Francis Fukyama’s pompously premature proclamation? Viera Čákanyová’s Notes From Eremocene (2023, above) performs its own bit of speculative filmmaking via auto-critical introspection. The writer-director mounts an expansive video essay, transposing the epistolary gambit of Between Revolutions into a dialogue between her future avatar and an omnipotent, cybernetic entity. Their oblique conversation guides us along philosophical digressions into the depths of a barely-fictive future where human society and the natural world have become subsumed into a digitised simulacrum.

The term “Eremocene”, coined by the late American biologist Edward O. Wilson, refers to an age succeeding the Anthropocene. In this age, human activity will be the only influence on a world totally effaced of biodiversity. Working from that precept, Čákanyová strives to reconcile her own place within a global society seemingly on the brink of collapse over the last few years. Environmental degradation, rising nationalism and a fundamental reshaping of perception vis-à-vis digital technology all coalesce into a pervasive loneliness.

The film has no shortage of visual experimentation as it toys with various dichotomies: the analog texture of film against demuxed manipulation of human footage; intricately pixelated forests set against the gaping maw of a black hole deep in the cosmic void. At the heart of these opposites lies the surprisingly simple quandary of ceding any connection to a dying species while confronting our own, unavoidable humanity. The contradictions Čákanyová lays bare within herself act as the guiding principle for a film whose intellectual rigour is informed by an intensely personal stake in our collective fate.

Treating an Ailing World

In their shared confrontation with physical and psychic trauma, these four films arrive at various and incomplete conclusions of how we treat an ailing world; how cinema can redress such flagrant wrongs before it’s all too late. Nick Cave, whose “Higgs Boson Blues” features in Notes From Eremocene, once wrote in a letter that “there is a vastness to grief that overwhelms our miniscule selves.” Yet what these films suggest is an unshakeable power in recognizing those we mourn through the images we put and watch — alone and together — onscreen.

Nick Kouhi is a programmer and critic based in Minneapolis, Minnesota