Conceived as a counterpoint and complement to the Competition section, Encounters, founded in 2020, has already become a home for some of the festival’s most striking work. This year is certainly no exception, with many films in the selection drawing plaudits, from Bas Devos’ Here (2023) to Dustin Guy Defa’s The Adults (2023).

As I made my own journey through this year’s eclectic Encounters selection, I found myself drawn to the work of three distinct filmmakers and the slightly nebulous golden thread that seemed to join them – echoes.

Familial Reverberations

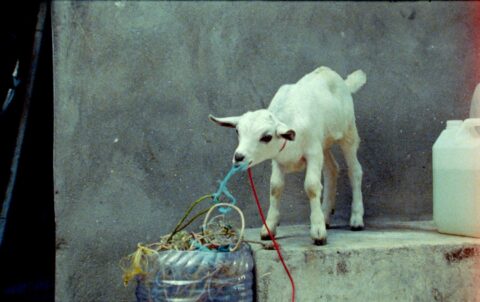

The source of the sound and thus the echo that resounds through my Encounters journey can rather appropriately be traced back to El Eco (2023, above) — the newest film by Mexican-Salvadoran filmmaker Tatiana Huezo. Set in a remote mountain community in Puebla, Mexico, El Eco is a film consumed by its natural environs as Huezo crafts an intimate portrait of a way of life and its intergenerational impact.

Filmed periodically over the course of eighteen months to capture changes in the seasons, Huezo’s film is one of quiet observation. The village of El Eco drifts from torrential storms to blistering droughts, with the lives of its inhabitants seeming to exist under a perpetual threat of collapse. While El Eco’s images, crafted by Huezo and her cinematographer/partner Ernesto Pardo, of the region’s natural beauty verge a little too close to cliché at times (sweeping shots of children’s hands rushing through long grass and drifting storm clouds are ever present), the film excels in its portrayal of El Eco’s children.

They are spared none of the village’s hardships. Through two girls in particular, Montse (Montserrat Hernández Hernández) and Andrea (Andrea González Lima), we glimpse the impossible choices they will inevitably have to make between family, community, education and independence; how all these choices are an echo of those made by their sisters, mothers and grandmothers before them.

Transcendent Reincarnation

Much like El Eco, Lois Patiño’s Samsara (2023) is essentially a film about the inevitable circle of life. But instead of leaning into the trappings of observational documentary, Patiño embraces the poetic and the spiritual, guiding us on a journey from one life to another.

Samsara is a film split in two joined by a bridge that almost defies description. It begins in Laos. A young man reads the Tibetan Book of the Dead to a dying woman and befriends a group of novice monks on a mesmerising trip to a waterfall. Reincarnation is an ever-present topic of discussion, as the dying woman decries people’s tendency to view reincarnation as an animal as a form of punishment. Despite these discussions, we still find ourselves woefully unprepared for what is to come following the woman’s inevitable death. As the young man finishes reading from his book, and watches over the woman’s body, a title card appears explaining the long journey the woman’s soul is about to take and inviting us to close our eyes until the journey is complete and silence falls.

What follows is one of the most profound and visceral experiences I’ve ever had in a cinema.

Defying description, it demands to be seen on the biggest screen possible more than any other film in recent memory. As we journey from one life to the next, we are greeted by ocean roars, pulsating flickers of light and an elephant’s trumpet. You find yourself overcome by a feeling of weightlessness, of becoming untethered, careening in and out of complete darkness and into reds, yellows, greens, and blues, oscillating between joy and fear in a remarkable sensory overload.

When we finally emerge in silence, after what could’ve been anywhere from ten minutes to an hour, we are greeted by a repetition, as water is sprinkled into a sleeping palm in a gentle attempt to wake someone. Earlier it was the young man doing it for the dying woman in Laos; now a mother does the same for her young daughter Mariam in Zanzibar, as she tells her that a baby goat has been born (later dubbed Neema). As we follow Mariam and Neema’s daily life we also glimpse the lives of their seaside community and the seaweed farming that sustains it. At times it feels as though this second part of Samsara might stray too far toward the observational approach that characterised El Eco – but thankfully Patiño instead opts to return his focus to Neema and the subject of reincarnation.

The echoes present in both El Eco and Samsara are distinct. In the case of Samsara one might say infinite. While Huezo’s observational approach traces the echoed actions and lives within the residents of one community, Patiño’s approach is decidedly more transcendent as these echoed lives and actions connect crabs with seaweed farmers and the life of a woman from Laos with a goat in Zanzibar.

The way of in water

in water (2023, above), the latest work by Hong Sangsoo, has already been covered here at Journey Into Cinema. Redmond elucidates just what makes the latest chapter in Hong’s ever evolving oeuvre both a fascinating continuation and a striking departure. Nevertheless, it seems absurd to present a view of the Encounters section that neglects mentioning cinema’s most inventive and daring filmmaker, particularly after wandering around Berlin for the last seven days shamelessly sporting a Hong Sangsoo tote bag.

in water, like so much of Hong’s work, centres upon an actor-turned-filmmaker (Shin Seok-ho) who decides to make a short film with his own money. While this simple premise wouldn’t strike anyone familiar with Hong’s work as unusual, the film’s images are certainly a diversion. As has been discussed at length, in water is out of focus. This generalisation does little justice to the variety of images Hong conjures by utilising this radical approach. I was fortunate enough to attend the world premiere of the film, and to listen to Hong carefully, quietly, and with his trademark wit answer questions with great generosity for nearly an hour. During this conversation, Hong was quick to point out, in response to someone asking why the first scene was in focus, that each shot varies in its level of focus. Some, like the interior shots, seem almost sharp, while images of the sea become almost indistinguishable swathes of colour.

The decision to shoot the film in varying degrees of focus was both one of spontaneity and premeditation. After casting his actors and deciding upon locations, Hong considered making the film out of focus, but it wasn’t until the very first shot on the very first day of shooting that he ultimately made his decision.

I couldn’t help wondering as I watched this film about a young filmmaker struggling through his creative process, whether this lack of focus was an elucidation of how unclear the creative process can be and whether only the final images of the short film the character is making would be in focus (if we were to see them). While a shallowly satisfying conclusion to draw, it is also one far more in line with the cinematographic tendencies of Hong’s actor-turned-filmmaker character, who in Hong’s words “is still young, and reaching for symbols”, than the man himself.

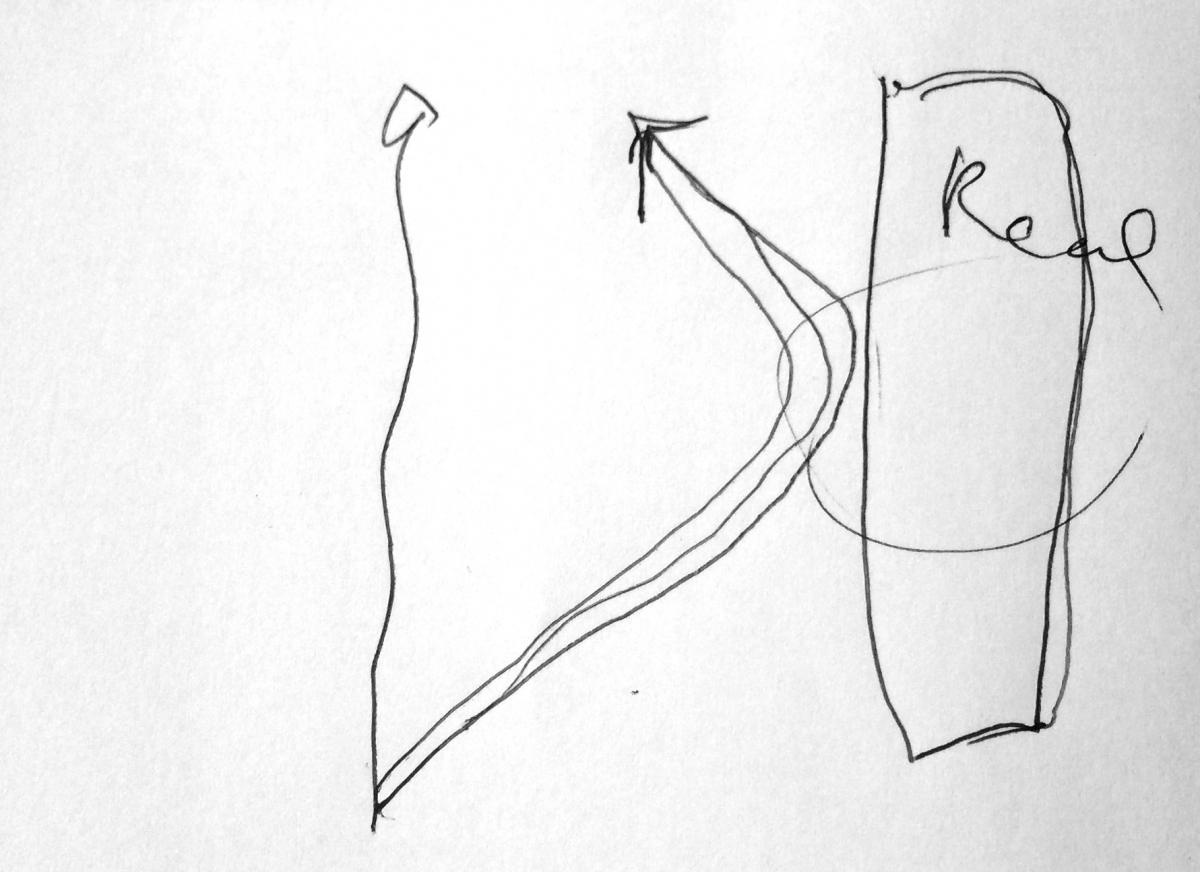

In perhaps the most intriguing moment of Hong’s Q&A, he returned to one of his now famous quotes and diagrams (pictured above), in which he describes his filmmaking process as following “an arrow towards reality, avoiding it at the very last second”. He mentioned that he felt the gap between reality and his films was getting smaller and smaller in recent years, as he finds himself drawing from things closer and closer to his current life.

While the echoes in Hong’s new work are in one sense foreshortening as he moves ever closer to his current reality, the import of his work to cinema only continues to grow, with each new film marking another volume in his vast human comedy.

Daniel Turner is a film curator and writer based in London.