I had a wish to swim in the clear blue sea before the day starts, but the sun hammered it down with such intensity I never ended up making it. While back home in Berlin, I have to watch out for falling chestnuts, the summer is still going strong in Antalya, with temperatures well over 30 degrees.

The beach bars, evidently for tourists, are relatively empty, the locals preferring to bring plastic chairs, huge vats of tea and their own shisha pipes to enjoy while watching the waves hit the shore. The stray cats are far friendlier and at ease than the house cats of Berlin, coming up to your legs while you sit, almost asking to be stroked. The dogs are not quite as friendly, chasing each other on the beach despite the no pets sign. I guess if they don’t have an owner, they don’t count as pets.

I saw all this walking back from the cinema as we ended up missing Mirror Mirror (Belmin Söylemez) due to spending perhaps five minutes too long in a bar overlooking this vast beach, drenched in a blue, widescreen haze, the mountains looming in the distance, cargo ships disappearing into the distance. I could pretend to be gutted, but these things happen. Let’s just focus on what I did see.

An Animated Prison

Two trapped women and their incredibly different lives — told in completely contrasting styles — dominated a pretty solid second day here in Antalya. First up in the International Competition was My Love Affair with Marriage (Signe Baumane, above) — a rare (or perhaps the only) Luxembourg-USA-Latvia co-production. An animated reminiscence of life in the Soviet Union told primarily in English, it was a delightful attempt to explain the ins and outs of life through biological means.

Not since Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain has the magic of romance been rendered in such a scientific way, the film utilising voiceover, greek choruses, musical montages, cutaway gags, and a boundless sense of imagination, telling us exactly what is happening to our protagonist Zelma as she has her first period, develops her first crush and, of course, falls deeply in love.

Set in the vastness of the Soviet Union, starting in the mud-splattered, primitive farms of Sakhalin island before skipping to drab Riga and artistic Moscow, the naive Zelma has to learn what it means to be a woman in a world dominated by ideology, with both funerals and weddings scored by the Soviet national anthem. While the storyline rarely surprises, it’s the excellent way that the film is told that keeps you totally invested, director Signe Baumane tracking not only one woman’s specific journey but the changing of eras and the softening of the East/West divide. The perfect film for both down-to-earth biologists and head-in-the-sky artists.

The entire time, the film is working against its conceit, showing us the magic of biology but also its limitations; the finale pointing towards a third, more revolutionary way to not just be a woman, but any kind of person whatsoever. It was just a shame that a film so musical/carnival-minded couldn’t end on a more fitting note, opting for simplicity when a riotous closing number felt more appropriate.

A Stereoscopic Vision

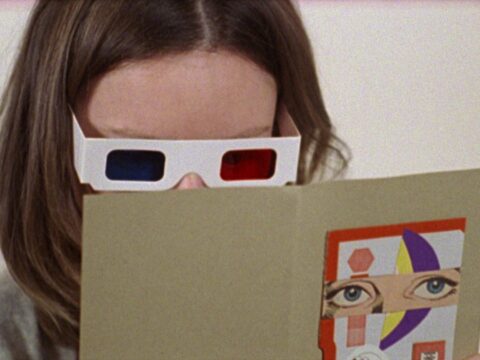

If animation was the only medium that My Love Affair with Marriage could’ve worked in — a full-scale live-action musical would’ve been exhausting — the formalist gimmick at the heart of National Feature Film Entry A Woman Escapes (Burak Çevik, Sofia Bohdanowicz and Blake Williams, feature image and above) was a nice-to-have, but never felt totally necessary. The 3D sequences throughout the runtime of this metafictional, epistolary tale, as much indebted to the video art of Bill Viola as the keenly observed humanity and production design and fonts of Eric Rohmer, were certainly interesting, but this fascinating, vibe-over-plot film didn’t really need them in order to keep my attention. The medium was a message, but not exactly the message.

The woman next to me wasn’t amused. When the little 3D glasses icon flashed in the bottom right-hand corner — indicating it’s time to awkwardly put these paper glasses over your eyes (or in my case over my glasses) — she actively sighed. She later left, along with a sizeable scattering of other people.

For the men and woman who stayed, there was so much to parse over during this demanding, slow, deliberately obtuse film, a series of video messages and letters sent between Audrey — living in Paris and looking after the flat of her deceased friend — and two men, Burak in Istanbul, Blake in the USA (ostensibly the two male directors playing themselves.) The latter mentions the idea of active boredom, repeating the same static processes perpetually, putting you into a trance state. And as I watched images like a mixture of light patterns beaming across the screen, fog filtering through a broken window, waves crashing against the beach in the “Asian part of Turkey”, a gondola moving slowly down a mountain, or a train crossing through a suburb, I kind of understood what he meant. This was a film where a lot and nothing happens all at once, all in an attempt to move the viewer into a feeling of disassociation. It absolutely worked.

Perhaps she was manipulating one message and sending it to another man, perhaps she was in love with her dead friend, perhaps there is some personal trauma that has been sublimated from non-fictional circumstances; either way, the film’s radical jumps in time, space and perspective — doing things that only the cinematic art-form can do — seemed to dissolve the boundaries between peoples and nations, to create a communal voice, an elegy for lost love and for chances missed. I’m not entirely sure, but I loved the experience nonetheless.

And, even if the film didn’t need it, I’m glad that the 3D was a part of the experience. Perhaps part of the subconscious reasoning behind naming this website Journey Into Cinema was partly due to the Chinese film Long Day’s Journey into Night (Bi Gan, 2018) — an inscrutable, typically Chinese arthouse project for the first half, it then refracts itself in the second half with a long 59-minute 3D tracking shot that truly expands the possibilities of cinema as a transportive experience. 3D is not just for the multiplex, but a fascinating tool that I would love to see more of in good-old independent films.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.