Some people become film critics to watch movies. I go for the spa hotels. Friday morning I made full use of both the Russian banya and the Turkish hammam, letting the toxins exit my body and prepare myself for the end of the festivities. Today was a simpler affair. A late wake up, some breakfast, the hotel buffet looking less appealing with each passing day. At first the variety of choice (despite no bacon) is a cool novelty, but by the end I just want a grilled cheese sandwich.

My final post shall combine the last two days, as I’ve only seen two films — preoccupied by a long lunch, endless conversations, all kinds of drinks and a slowly thinning schedule. Nonetheless, they seemed to compliment each other rather well; exploring the epic tides of history and the way people define themselves in times of war.

Living Happily Despite the War(s)

I’m not sure I’ve ever experienced stop-motion quite as nakedly artificial or metafictional as Another World selection No Dogs or Italians Allowed (above), charting French director Alain Ughetto’s own family history in and around the Piedmont region of Italy in the first half of the 20th century. Allowing direct interaction between his physical hand and the landscape he is creating, it shows that the act of remembering is also an act of conscious creation.

We start with him glueing pieces of cardboard together. They will come together to form a house. He carves models out of pieces of wood. These cute creations will become his ancestors. Soon he is able to talk directly to his grandmother, who tells him the story of her husband Luigi. A simple man, but good with his hands, he toils and toils to create a life for himself and his family. But these are poor people, cutting a single potato into several pieces to feed each one of his children. Soon they are forced to work as immigrant workers in southern France and Switzerland, where Italians were often-treated like second-class citizens.

With both a sense of the whimsical — like broccoli standing in for trees — and a serious inquisition into historical circumstance — especially as poor people are used as cannon fodder in the Libyan and Great Wars — No Dogs or Italians Allowed uses its central conceit to get deep into the way these people lived and the great hardship they faced, before finally finding a happy life for themselves in France. It shows that nationhood can be something you can choose rather than an inevitability, Ughetto’s family far more grateful towards France for the higher-paid work and the chance to escape the rise of fascism back home.

And the metafictional approach isn’t just a nice gimmick, but the entire point of the film. We sense that this skilled physical labour finally found its way down to Ughetto himself. This is his touching love letter to them.

Epic In Every Single Way

There’s something lovely about ending a film festival with a Rifkin’s choice: instead of gambling on a new film that may or may not be any good, diving deep into a classic on the big screen can be an immensely rewarding, transformative experience. And what better film to see on the big screen than arguably one of the biggest and widest uses of the cinema format of all time.

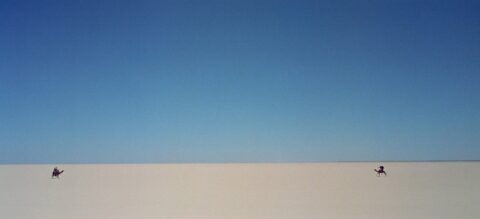

It’s no surprise that seeing Special Screening Lawrence of Arabia (David Lean, 1962, feature image and above) on a huge screen is a great experience. What I was not prepared for was simply how purely elemental certain sections would feel. There’s one scene in particular that had me in sheer awe. After crossing the Sun’s Anvil section of the Nefud Desert — a place so piercingly hot that it’s simply not possible to cross during the day — they realise that one man fell off his camel. The cynical Sherif Ali (Omar Sharif) tells him not to go. But Lawrence persists. He is simply not a normal man.

This is a sequence shot with stunning, epic simplicity. We watch the sun slowly rise over the landscape, the Super Panavision camera capturing the sweltering heat just about to devour the landscape. The desert and the sky meet each other in the middle, a colour combination so pure it looks like a Rothko painting. The editing by Anne V. Coates cuts between Lawrence, the lost man and one of Lawrence’s boys with precision, creating a ever-rising sense of tension. Meanwhile, the sun keeps floating higher in the sky, showing us what is at stake. But Lawrence makes it in the end, crowning this strange outsider as the real deal. The whole thing, mixing pure elements of sun, sky, sand, heat and water, provides a cinematic experience at its most universal and powerful.

The other shots — the Bedouin emerging out of the shimmering heat, the shots of camels that look like black dots in the sand, Lawrence riding his motorcycle near the start — have been firmly etched into the cinematic consciousness and don’t need much further praise, but it’s the pure assembly of these images, edited with an undated modernist verve by Coates, that makes for one of the most sublime experiences I’ve ever experienced in the cinema.

What’s worth noting is just how strange Lawrence is. His obsession with and appropriation of Arab culture, his admittance to sadomasochism, the glimmer in his eyes when he shoots people, the way he prances about when he finally has his tribal outfit, and his blatant repressed homosexuality, make him probably the weirdest guy ever to unite the Arab tribes against the Ottoman Empire. It’s a bizarre film to make it into the canon, with no happy ending, a truly cynical view of politics (I was shocked by how blithely Prince Faisal (Alec Guinness, very dated brown-face) dismissed Lawrence once he finally left Damascus) and a very obviously gay hero.

But I’m glad it is there. It’s an obvious masterpiece. I’ll try to keep this kind of pointless coverage (“critically-lauded at the time film still good x years later”) to a minimum in the future, but in the case of Lawrence of Arabia, it was simply unavoidable.

And that’s that. See you at the next festival.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.