I make no secret of my love of the Berlinale Shorts. They are weird, they are bold, they are often sexy, and there’s always one or two movies that dig deep into the cranium. And even when a significant minority of choices are exceptionally boring and/or misguided, there’s rarely anything in there that feels like it hasn’t been chosen with a particular idea or aesthetic in mind. In fact I love the Berlinale Shorts so much, I’ve decided to watch and review every movie, split over two dedicated posts (and one standalone review.) Let’s dive in already.

Eccentric Animations

Mother’s Child by Naomi Moir (2025)

The images in Mother’s Child are leering and garish. Half-composed faces, blending together, caught in a web of ever-shifting 2D drawings. A working-class British woman, facing down the sharp end of austerity while looking after her son with cerebral palsy, is stuck in “On-Hold-with-the-Government Land,” a murky and miserable quagmire with little happiness emerging from the sludge. Yet, through the film’s acute ear for dialogue, quintessentially English details (an ugly bulldog, bald-men-in-the-pub, a propa cup for tea) and oneiric tone, Moir creates a sense of hard-won empathy, making the impossible feel a little more bearable.

How Are You? by Caroline Poggi, Jonathan Vinel (2025)

Caroline Poggi and Jonathan Vinel are the iconic co-directing team behind Jessica Forever (2018), one of the most annoying, banal and nonsensical arthouse films ever made. I tried to clear that atrocity from my mind and go into How Are You? with an open mind, but it’s clear that Jessica Forever was no mere fluke (derogatory)! With this exceptionally ugly and annoying CGI animation, utilising ugly 3D kids’ cartoon aesthetics to portray a bunch of lonely animals washed up alone on a remote island, they display a remarkable ability in creating truly unwatchable cinema. If Guantanamo Bay are ever looking for in-house content creators, they should definitely apply.

Stone of Destiny by Julie Černá (2025)

The eponymous Stone of Destiny resembles a grey Grimace mixed with a mushroom, suffering from loneliness and confusion in a bright and garish musical cartoon mash-up. With David Hockney-esque colours, bedroom pop music and a willingness to embrace the weird, Černá’s bachelor film at UMPRUM University in Prague is a beguiling and oddly entertaining experience, replete with strange demons, beautiful horses, empty fields and Bojack-like beachside houses, following Destiny as she tries to see more of the world, or something. It’s probably about mental health, but I couldn’t tell you much more than that.

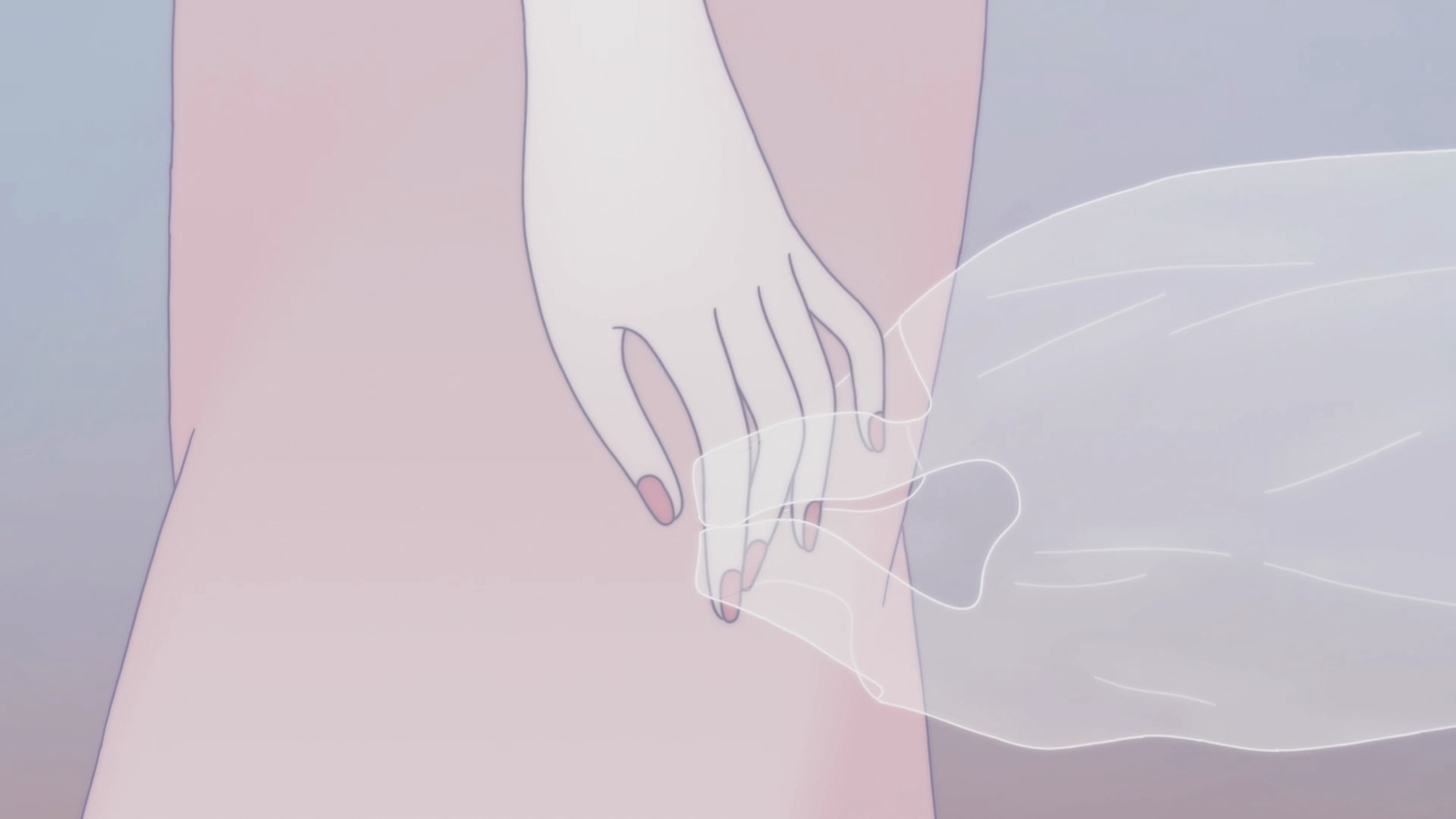

Ordinary Life by Yoriko Mizushiri (2025)

Domestic scenes in soft pastel hues. A dog’s nose. The aimless movements of a plastic bag. Shoelaced feet tramping across the ground. Mizushiri’s animation, buoyed by a dreamy soundtrack by Kengo Tokushashi, is simple in its presentation, but feels dense in ideas. Essentially a ten-minute Japanese montage of everyday things, its use of juxtaposition, circular imagery and shapeshifting designs creates an oddly rapturous effect, even if, like in Stone of Destiny, final meaning is elusive.

Enter Indonesia

Sammi, Who Can Detach His Body Parts by Rein Maychaelson (2025)

With its theme of malleable body parts, the Indonesian Sammi (feature image) pairs nicely with Ordinary Life, focussing on a young man with the magical ability to give parts of himself to others. Usually, it’s when I watch a particularly protracted feature film that I think: “This could’ve been a short.” But Sammi’s ingenious structure, telling the story of his mother looking to return the deceased young man’s body parts back to him, practically begs to be, for lack of a better word, fleshed out. One extremely provocative scene in particular will stick around in the memory for a long while. Bizarre in all the best ways.

After Colossus by Timoteus Anggawan Kusno (2024)

Exploring a series of unearthed bizarre experiments — mind control, man-tiger-transformation, the manipulation of dreams — by the Suharto dictatorship in Indonesia between 1965 and 1998, After Colossus is a deeply obtuse experience, obliquely navigating the horrors of dictatorship through low-res reconstruction, off-hand dialogue, disembodied voices and a mixture of film formats. I found it extremely hard to get into. The post-script disclaimer claims to have generated certain assets using AI — this feels like a deeply irresponsible choice when dealing with topics as serious as statewide repression.

Singapore Stories

Children’s Day by Giselle Lin (2025)

Every year, one or two lovely shorts come along that make an excellent case for the vitality and versatility of Kodak film. Using a soft, sun-hued colour palette bursting with light and emotion, the images of Children’s Day have a delicate nature to them, perfect for encapsulating the inner struggle of the eight-year-old Singaporean girl Xuan as she figures out what to wear. Usually, girls are all equal at her school thanks to the enforced uniforms, making this one-off-wear-what-you-want-free-for-all a source of tremendous angst for the thoughtful young kid. Capturing her familial and student dynamics with fleeting ease, this tender-hearted story is easily one of the standout Berlinale shorts.

Through Your Eyes by Nelson Yeo (2025)

Discotheque dreams intertwine in bisexual lighting, Cantonese-musical bits, strobe effects and hallucinogenic overlays, amounting to an intermittently engaging yet ultimately superficial experience. It felt like images in search of a film rather than a complete work in and of itself. Gorgeously lit and framed — neon blues, crimson reds, verdant greens — but thematically rather empty.

Superficial Intelligence

Their Eyes by Nicolas Gourault (2025)

Big tech’s dirty secret is that all of these incredible advances in software are built upon the exploitation of the Global South. Their Eyes focusses on workers from Keyna, Venezuela and the Philippines as their painstaking labour is used to build the technology to power self-driving cars. We watch their computer screen as they label people, cars, motorcycles, poles and signs with meticulous detail, creating the vast amounts of data that allow self-driving cars to navigate the street without running over and killing anyone. Mixing disembodied matter-of-fact narration with hallucinogenic, nightmarish, night-vision goggle-esque images, Their Eyes comments on low wages, depersonalised globalist labour and a world increasingly losing its humanity to the never-ceasing advances of AI.

Citizen-Inmate by Hesam Eslami (2025)

Citizen-Inmate delves into Iran’s dystopian surveillance network and its complex ankle-monitoring system with a mixture of down-to-earth images and an unreal presentation. The men tasked with enforcing Tehran’s tedious ankle-monitoring laws — making sure no one goes outside their perimeter or fails to inform the centre of any unexpected trips — are obscured from behind, mere cogs in the wheel of a much bigger, much more nefarious system. Complemented by eerie music, uncomfortable close-ups of computer systems whirring and spooky black-and-white CCTV footage, this is an assured look at the banality of total state control. It makes me wonder why on earth some people I know willingly track each other’s location on their iPhones!

Read Part Two here!

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.