Arsenal Kino, 35mm

With an hour and a half to while away between Zoologischer Garten and Potsdamer Platz, I skipped taking the U2 or the S7/S3/S9 or the 200 bus and walked in the rain through streets dotted with ugly embassies and bleak monuments. Sleek, gleaming functional buildings. Hotels. Chain restaurants. Grey, rainy, uninteresting. Lydia Tár country.

Ukrainian flags punctuate the skyline. Not everyone appreciates the effort. Someone wrote “#Das ist nicht unser krieg” (this is not our war) on a wooden fence. But someone else crossed out “unser” (our) and replaced it with “auch”.

Now it reads: “This is also our war.”

Here in Berlin — the mittelpunkt of the 20th century — it certainly feels like it. The war is a never-ending prospect. A constant source of anxiety. A thrumming, buzzing, hateful, pointless cause of misery. But despite it all, life goes on. It has to go on.

If you need yet another sign of the resilience of Ukrainian expression and culture during these times, consider this: the 35mm print of Brief Encounters (1967), kicking off a Kira Muratova retrospective running April 1-23, was shipped to Berlin all the way from the Dovzhenko Centre in Kyiv. The culture war pales infinitely in significance to the actual war, but highlighting this exquisite product of the Odessa Film Studio is certainly a way of contributing to Ukrainian autonomy during this difficult time. It’s just heartening to think that despite such evil, desperate times (perpetuated by those with zero respect for culture and empathy and art whatsoever), the importance of curation, preservation and archiving still holds strong. Art, expression and history must hold on.

Kira Muratova is being reclaimed. As a female filmmaker and as a Ukrainian filmmaker. The latter question is a little more complicated given she was born in Soroca, Romania (now Moldova) to a Russian father and Jewish-Romanian mother, worked almost entirely in Odessa and made her films in Russian. Complicated, heated, questions of nationality aside, she is easily one of the most critically neglected filmmakers in history.

Some voices have already banged the drum: Mark Cousins in his 14-hour Woman Make Film series (haven’t seen) and critic Bianca Garner, who writes:

“Her films remain nearly impossible to track down outside of Russia. And, while she should be talked about and her work should be studied in Film Studies classes across the globe, I’m pretty sure that her name barely gets a mention…”

The good news: Arsenal Kino are now showing ten out of her 15 features made between 1967 and 2012 in the first Berlin retrospective of her work.

Amazingly, not a single one of these made it into the recent, somewhat spurious, Criterion Collection/Janus Films-skewing, Eastern-European (and Latin American) eschewing, Sight and Sound Poll.

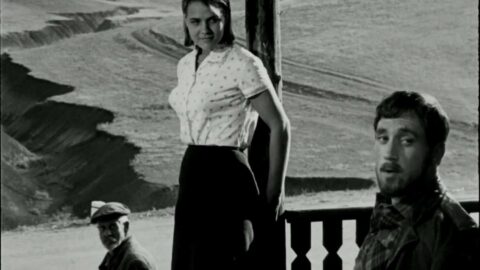

Brief Encounters (no relation to the David Lean classic) is her first solo film, after making two features with her husband, Aleksandr Muratov. It was removed from circulation after completion, enjoying its first screening in 1987. My second experience with Muratova after Getting to Know the Big, Wide World (1978), this film is irrefutable evidence of her immense talent as a director, a woman who found epic potential in the most simple-seeming of scenes.

The Domestic Epic

The success of Sight and Sound Poll 2022 winner Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (Chantal Akerman, 1975) has reinstated that feminine concerns are as worthy of critical attention as any gangster shoot-em-up, horseback ride across the horizon or bridge blowing up over the River Kwai. I’d tend to agree. The quotidian, the banal, the everyday is as interesting as the epic. And in a dark, comforting cinema, on a beautiful film print, when the masking is perfect and everyone is off their phones, it can even feel epic all by itself.

But before Akerman and her structuralist revolution, embedding feminist poetics within a constructivist space, there was Soviet filmmaker Kira Muratova. Like Georgian Soviet director Georgiy Danileya (even more neglected in film history) hiding criticism of the system within his “sad comedies”, she embeds feminine, “womanly” concerns within the structure of classical melodrama. Seeming at the time to be a small, domestic picture, her debut film is alive with romantic, expressive, expansive possibilities.

Flowing between close-ups, medium takes and granular detail all in the same shot, her opening one-take captures the contrast between Valentina Ivanova’s (Muratova herself) work concerns and domestic woes. On one hand, there is her prospective speech to the agricultural committee. (She can’t yet get past “Dear comrades.”) But there are also the dishes piling up in the sink. There are the broken plates. There are the mismatched forks, knives and tea-cups.

She might be a prominent figure in the complicated bureaucratic Soviet system — responsible primarily for connecting housing blocks with the often non-existent water supply — but her domestic duties lie woefully undone.

Part of every relationship, is, of course, doing the dishes. On the latest season of Love is Blind, couples moving in together for the first time have the all-important dishes chat. (I was amused by one man, Kwame, saying that he will aim for a clean sink 80 percent of the time — a failed attempt to anticipate less conflict in the future by carving out a 20 percent quotient for excusing yourself.) But doing the dishes is a lot easier when you have someone to do the dishes for.

Valentina’s husband, Maxim (Vladimir Vysotsky), a geologist, is constantly away, leading her to dive into her work and await the day until his return. Vysotsky, a singer-songwriter with Sinatra-level fame across the Soviet Union, is perfectly cast: his boyish face, spontaneous guitar interludes and overall immaturity, speak to someone who wrote countless songs on every theme imaginable, suppressed by the system, touring the length and breadth of the biggest country that ever existed to try and promote his work.

A mythical figure in Russian culture, he is also somewhat of a mythical figure in the film itself: glanced only through flashbacks. He is gone so long that Valentina says that has to invent him, create a version of him as the reality slowly slips away. So not only do we have a smart feminine subversion of women’s duties — we also have the female gaze. Women looking at men, thinking about men, imagining men.

And not once, but twice! Nina Ruslanova — at times looking like Florence Pugh somehow Zelig-ed (Woody Allen, 1983) herself into the past — plays the spunky, vivacious, curious and confused Nadia. She comes from the countryside and finds a job as Valentina’s maid. Finally, the important city council member doesn’t have to worry about the dishes.

Woman and The State

What follows is a dual-narrative, elliptical, imprecise, emotion-driven — and very, very generous. My favourite moments, recalling what I remember of Big, Wide World, contrast these singular, complex lives against the vast, impersonal progress of the state. Valentina, a symbol of parallel progress during the Soviet Union, where women could actually become in charge of men — a truly emasculating prospect best encapsulated by Eldar Ryazanov’s gender-flipped satire Office Romance (1978) — is seen amidst a huge building site; rutted roads, wetness, construction work, men in hard hats. They surround her at every moment. And she’s telling them what to do. One of them opines that life was better during the war, as there were no women about.

And the horrors of Ukrainian history, a backdrop within the film, show us how so little has changed since 1967. An old man accosts the two women in a cafe. He tells Nadja that she shares a name with his daughter, who died during the German occupation. He later repeats a similar story to another couple. But this time his son died. Ironically enough, laments Valentina, both stories are true. Life marches on regardless.

Its sense of life on the margins does for this anonymised city (I assume Odessa, but it is not specified) what I wanted Rye Lane (Raine Allen-Miller, 2023) to do for Peckham. The wide-angle lens and local, charismatic weirdness and colour in that film was excellent to see, but it wasn’t embedded in the frame in a satisfying way. Inserts and interludes can work, but I wanted to see Peckham all around the frame — not just in awkward montages. Brief Encounters, conversely, holds a take of Valentina talking to a bureaucrat about the water supply while children ride bikes in the background and goats flitter in and out of the frame. By flattening the two things within the same shot, culture and character, setting and situation unite. It’s an insanely enjoyable mise en scène.

The Power of a Simple Cut

If I’m describing Brief Encounters as all long, flowing takes, à la Andrei Tarkovsky or Alexei German (both senior and junior), Muratova also, excellently, utilities the power of a simple, ostentation-free cut to flatten present and the past — and to unite two backstories around the same man.

As it turns out, in what could’ve been material for a laborious, histrionic, brow-beating melodrama in the hands of another director, Nadia the humble maid — switching her style between a modest headscarf and a full, expressive head of hair depending on her mood — has more in common with the high-power official than either can ever know.

In a simple transition from looking at a guitar in the apartment and into the past — no dissolves, no whirling music, not even a fancy match cut — we learn Nadia’s own special encounter with Maxim. Working as a waitress at a roadside cafe, she is immediately taken by his easy-going charm. Geology was exalted in the state ideology of the day, with the intrepid adventurers — warming themselves around campfires, singing songs, sleeping under the stars — romanticised and compared to wandering gypsies.

Valentina’s flashbacks are certainly more complicated. She’s older, more complex, looking for more from her man. But he is totally unable to take anything seriously. If American 00s cinema provided us with the Manic Pixie Dream Girl — a woman impossible to truly comprehend due to their immense whimsy — Muratova provides us with a Manic Soviet Bard Guy, too romantic, too generous, too excited with life out in the big wide world, to simply settle down and worry about the dishes.

With these spontaneous-feeling flashbacks, Muratova, working with a script co-written by Leonid Zhukhovitsky (who died two months ago), carefully delineates the differences between these women while situating them within a similar shared history. Then in present-day, domestic settings, the relaxed, intuitive blocking — an art form seriously in need of revival regardless of nation or tradition — allows Muratova to follow one character closely while two others are talking, or to focus on hands or gazes or internal emotions — to move between medium shots and close-ups, to see both the bigger picture and the smallest of hidden feelings.

Right Where She Belongs

It’s at once a film about the specifics of individuals and the larger machinations that drive them — either into the hands of the state machine, like Valentina, or away from everything, like Maxim. Like the best Soviet Cinema, this satisfyingly, warm, open-hearted close-up of modest lives in the midst of extraordinary social change, brims with ideas and feelings and a willingness to create that elusive sense of the epic within the constraints of a “domestic melodrama.”

I’m reminded of a little bit of another Akerman, News From Home (1977, above) — its insanely long takes from the back of a taxi cab, as well as that never-ending final shot of New York receding into the distance — expanding a previously epistolary, small-scale film, into something vast and unconquerable — an object of awe.

Not every idea here is fully formed, and there are frustrating moments as the film stalls for a conclusion. With such a fascinating diametric put between both women, I wanted some catharsis, some synthesis, to make for a pleasing resolution. But Muratova seems uninterested in convention — probing amongst the spaces to create a fascinating reverie on realistic feminine lives during moments of top-heavy upheaval.

These subtleties in her tone can be hard to absorb on the small screen. I remember enjoying parts of Getting to Know the Big, Wide World (1978) online while struggling to maintain full, undivided concentration. That’s why Arsenal Kino’s retrospective is such a lovely thing — especially on gorgeous, crackling, shimmering film. It takes Muratova’s work out of the vault and puts it in front of excited, empathetic audiences — showing off this Ukrainian, Russian-speaking woman auteur as a true titan of cinema. It’s time for the big wide world to get to know Kira Muratova.

—

If you read all this, are you ok?

Anyway, I’m following this piece with one on The Asthenic Syndrome (1989) (live now). It would be lovely to sit and watch Muratova movies for three weeks, but alas, I have other things to do. Obligations. Sign up for the newsletter now.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.