Travelling to Austria on the train is always a pleasure.

I still have fond memories of travelling during corona, people taking off their masks as they crossed the German-Austrian border. A friend asked the train conductor if we were in Austria, and he seemingly referenced the looser COVID restrictions by saying: “Ja. Frische luft, freundliche gesichter.” (Fresh air, friendly faces.) While the architecture between Bavaria and Austria barely changes bar the font at train stations, the landscape does become noticeably more mountainous, the train tilting as it careens into the city of Linz, a mere 19 miles south of the Czech Republic.

I’d previously been to Linz, but I’d never “been to Linz” been to Linz. To put it simply, I transferred at Linz Hauptbahnhof twice. Once on the way to České Budějovice. Once on the way to Vienna. Both times, I sat in a café in the corner of the station, nursing beers while waiting for my transfer to somewhere else. Now, thanks to Crossing Europe — Linz’s celebration of European cinema — I’ve finally been to Linz, been to Linz. Not just at the station. Right in the heart of the city itself.

As I walked through the Volksgarten and down the main boulevard to my hotel, past homely Würstelstände and buzzy terraces, the spring sun illuminating the city in bright, verdant colour, it felt deeply satisfying to have finally unlocked this super-typical central European city; the ideal location to sample a wide variety of auteur cinema from all across the continent.

And the Movies?

The first day delivered on that ideal, with my first two films — a documentary about surrogacy from Georgia and a whimsical black-and-white father-son drama from the Netherlands — completely stylistically and politlcally opposed, yet somewhat tangentially linked by the vague theme of parenthood; what it means to truly love your child and the immense difficulty of making sure you don’t fuck them up.

We kicked things off at the no-thrills Moviemento Kino, located in the OK Insitution for contemporary art, a brutalist building with high ceilings, large windows and graffitied staircases. I particularly enjoyed hanging out before my screening in the sunshine-filled OK Platz (above), with a cash-only beer stall and plenty of seats for people to congregate before and after films. It’s the kind of space the Berlinale — going through a vibe crisis right now — desperately needs for people to have fun between screenings. It certainly put me in a much-needed good mood for documentary competition entry 9-Month Contract (Ketevan Vashagashvili, 2025), a harrowing look at the surrogacy industry in Georgia through the brutal experience of one woman.

The Pitfalls of Surrogacy

Ketevan first met Zhana 12 years ago, when she filmed a documentary short about the teenage mother growing up homeless on the outskirts of Tbilisi with her daughter Elene. Her debut feature revisits the mother and daughter as they are off the streets and into rented accommodation. Now Elena is a teenager at school herself, while Zhana struggles to make ends meet at her dollar fifty an hour job in SPAR. To supplement her income, she is a surrogate; her body hosting someone else’s baby for a grand sum of 14,000 dollars.

This is not only her fourth pregnancy, but her fourth C-section, making for potential life-threatening complications. Not that the surrogacy agent seems to care, neglecting Zhana in terms of both medical care and compensation. Through conversations with the camera and a local women’s rights org, we clearly understand how unrelegated this business can be, putting lives at risk in the pursuit of naked profit.

If you are squeamish about medical dramas, 9-Month Contract — which features live birthing footage — is not the movie for you. But Vashagashvili’s intimate, personal camera, sacrificing objectivity for a direct connection with its subject, avoids exploitation, instead capturing the inner turmoil of her hero.

Despite her emotional and moral intelligence, as well as complications in delivery, Zhana is constantly lured back to surrogacy by a difficult concatenation of circumstances, including the increased cost-of-living due to the COVID pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. It’s the way the latter development, as well as Georgia’s difficult stumbles into freedom, is woven into this film that makes it such an accomplished work, rising beyond the struggles of the individual to create a fascinating portrait of a nation on the cusp of potentially historic change. With crisp and propulsive editing, this seemingly small film slowly grows into something rather monumental.

Fatherhood, Dutch Style

All three cinema venues are within a five-minute walk of each other, so it was easy to make it to the City Kino with just a 20-minute break. I even had enough time to pick up a bosna from Jörg’s Würsteltreff. The bosna — ironically invented by Bulgarian immigrant Zanko Todoroff— is a type of curried and spicy sausage that originated in Salzburg, and is a must-have item across most of the country, as well as certain parts of Bavaria. I ordered an even spicier variation with two sausages packed closely together, which I have to say, was not very spicy at all — more piquant if anything — but certainly packed full of wonderful flavour.1It was only later that I was told that a “better” Bosna can actually be found at Auinger Würstelstand, which is literally on the other side of Jörg’s. There I had the “super-spicy” Balkan Bosna, which was just one sausage but much, much heavier on the spice quotient. Not better, per se, but certainly more substantial. And spicy!

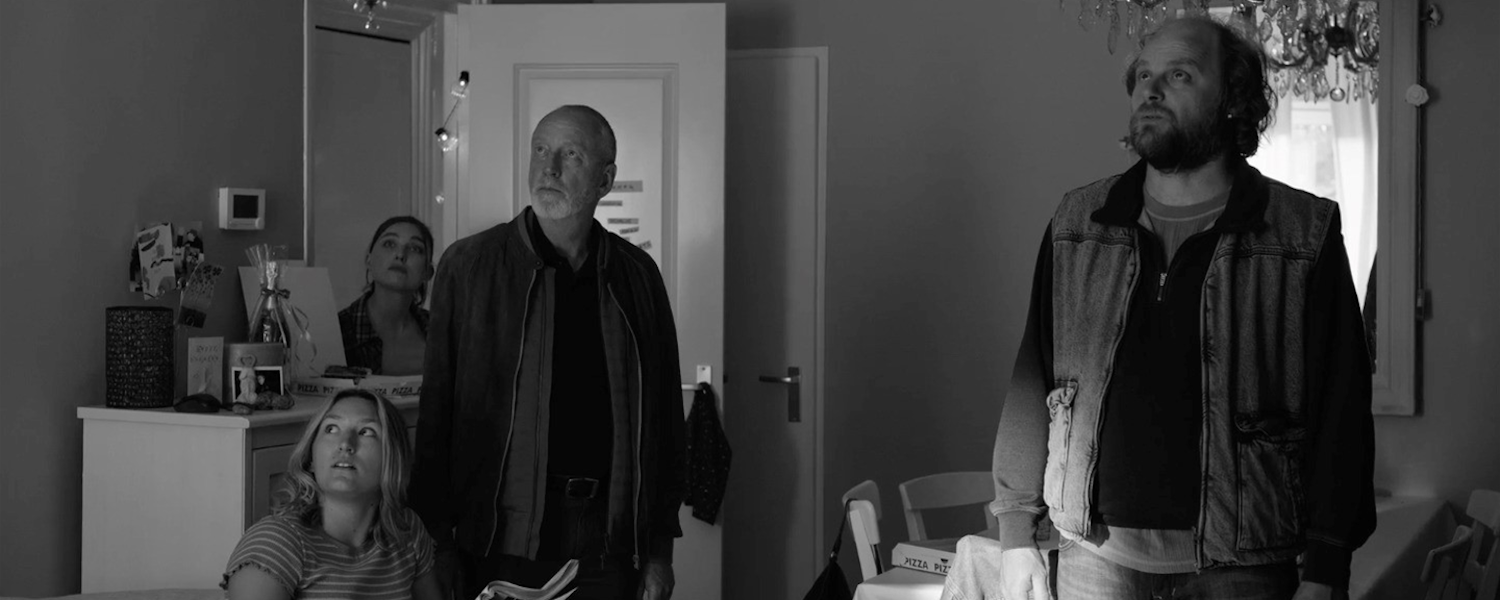

It filled the gap for my second screening at the also-fairly bare bones City Kino, albeit complemented — like all cinemas should be! — with an in-house bar. Its austerity felt perfect for Three Days of Fish (Peter Hoogendoorn, 2024), a wistful, sad comedy that uses black-and-white and a huge widescreen frame to create a very specific and sustained kind of emotion.

The aforementioned three days refer to the amount of time that Gerry (Ton Kas) — a Dutch expat living in Portugal — spends in Rotterdam to sort out a variety of bureaucratic issues, as he is still legally registered in his home country. And for Dick (Guido Pollemans), it’s much-needed time to bond with his emotionally withdrawn father. Together, they get in all sorts of low-key japes as they realise just how alienated they have become from one another.

It’s the kind of comedy where you laugh on the inside. There are amusing bits, including a clever-clever riff on “Dutch Coffee,” but the jokes are meant to bring more introspection than anything truly cathartic. With both wistful oboe and French horn on the soundtrack, Hoogendoorn lays the oddball pairing on thick. He nobly avoids sentimentality, but unfortunately, never overcomes the slight allegations. Nothing objectionable, nothing really worth raving about either.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.