Radu Jude’s punky, itinerant new film makes good on its title: there’s little in the way of hope or yearning.

We follow a day in the life of Angela (Ilinca Manolache), a production assistant for a video company, as she drives around Bucharest and its hinterlands, combining family chores with a punishing work schedule. She spends long hours visiting, interviewing and recording testimonies from people who’ve been disabled in the workplace — but for the benefit of the murky and nefarious Austrian firm that employed them. (Nina Hoss fills in as the arch, dispassionate marketing director.) The title’s helpful admission that they’re unlikely to be saved, much less redeemed, provides a kind of sanguine clarity. The apocalypse is coming. Don’t lament the bang; celebrate the whimpers you made along the way.

The narrative mainly situates Angela in her car as she ticks off her to-do list, and the camera holds her predominantly in profile as she rubs her eyes, blows bubble gum and regales adjacent traffic with an assortment of fuck yous. The front seat is rendered as a noticeably physical and sonic space that heightens its occupant’s beleaguered disposition. Our protagonist glances fitfully out the window, wrangles with the gearstick, and listens to the radio with the volume turned up. Anything to drown out the cacophony: the insistent ringtone of her mobile; the deafening downward pressure of the spoiled metropole. There’s no escape: at one point, Angela vainly attempts to cross a path encircled by roaring go-karts.

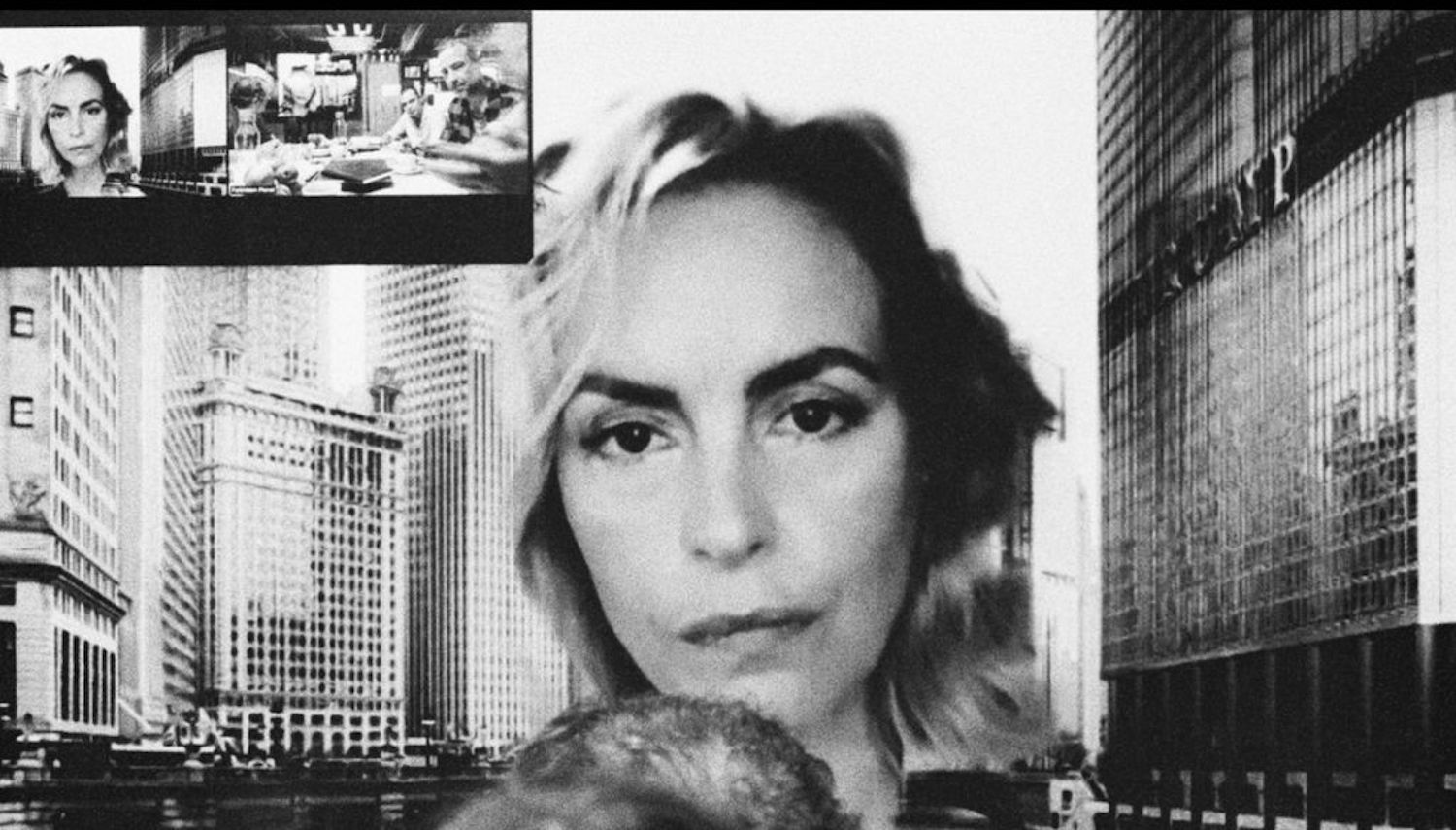

Angela’s picaresque journey is accentuated by the film’s form. Her world is mostly depicted in grainy monochrome — lush, enigmatic, strangely iridescent — but punctured by lurid shafts of light. She breaks up her monotonous existence by filming herself as a crass Andrew Tate-caricature, delivering misogynistic missives, praise for dictators and casual citations of esoteric political theologians. These parts are very funny: not so much for the intended ironic offence, or for revealing Angela’s learnedness, but for the absurd video filter that supplies her with bald head, bushy eyebrows and goatee, leaving her natural blonde hair to occasionally flicker into view. Playful, provocative: parody infuses the world with colour.

Jude’s other visual trick is to splice the dominant story with the Romanian film Angela Moves On (Lucian Bratu, 1981), about another Angela (Dorina Lazăr), as she navigates Bucharest in the Communist era, before neighbourhoods were flattened to accommodate Ceausescu’s gargantuan presidential palace. Jude slows down, halts and reframes these bright, saturated excerpts, the disjointed zooms and cuts offering an unsettling counterpoint to the contemporary setting, not so much bringing it up to pitch but gesturing at the wry and despondent historical parallel. While these interludes appear digressive, they are in fact calibrated. Much like Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn (Radu Jude, 2021), the present is portrayed without fuss: people wear masks, go on TikTok, hold Zoom meetings.

Jude is fascinated by these different mediations of reality, and by the malleable quality of images more generally. In the most striking sequence, the film pauses — inasmuch as this act is possible — to catalogue in photographs a series of roadside crosses, memorials to those who’ve died along a treacherous route on the outskirts of the capital. The pictorial rhythm suggests a sort of ending, but what follows is a clear, didactic statement of political intent. One of the disabled interviewees (Ovidiu Pîrșan) is brought along with his family to take part in a sanitised video that absolves the Austrian firm of blame for his accident. During the final hour of the film, this family portrait is kept in fixed perspective; the deliberate failure to present a reverse angle suffocates the characters’ space and implicates the viewer in their predicament. The extent of corporate corruption and civilian indifference that damns them is vast, expanding and fundamentally unknowable.

This fact is simply demonstrated in one earlier scene, where Angela leaves the revolving door of a hotel foyer, despairing that she just can’t take it anymore. Like a joke, the doorman responds, “That’s what you think!”

Joseph Owen, occasional film critic, is a research fellow at the University of Southampton.