The sun is finally out. What once felt baroque and gloomy now has a certain piquant charm. Between Cinestar screenings, I stumble into the Nikolaikirche, a typically plain and Protestant Church with few ornamental details but a small exhibition dedicated to J.S. Bach. The phrase “Es ist genug” (it is enough), referring to a Lutheran hymn Bach adapted for his Church cantata “O eternity, you word of thunder,” (BWV 60) adorns the walls. This is where many of Bach’s works were performed, perhaps including “Air on a G String,” (BWV 1068) played by a street performer as I walk past looking for somewhere to eat. I settle for a Bohemian chain restaurant and order gulaschsuppe.

The typically Hungarian dish, popular in Germany, pitifully small as it was, complemented the morning’s screenings, two Central European animations playing in competition about the collapse of communism coupled with the sudden possibility of escape and adventure. In a smart choice, the type that regular cinemas should consider bringing back beyond Pixar screenings, a short preceded the feature, allowing for a stimulating appetiser before the main course.

(Post) Communist Cartoons

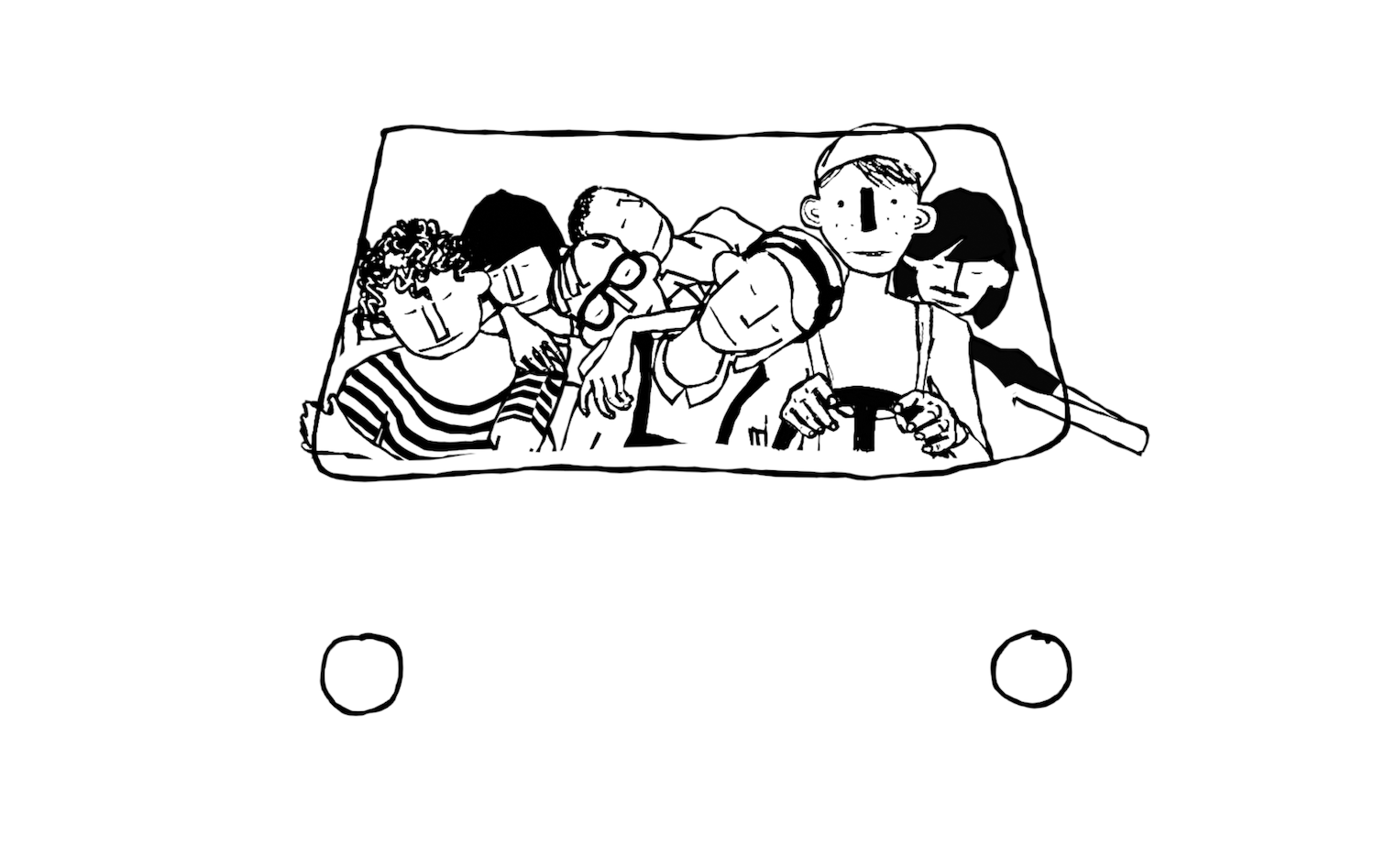

We begin with the fiction short The Car That Came Back From the Sea (Jadwiga Kowalska, 2023, feature), set in Poland in 1981. It is a time of deep recession, where there is no money for bread, butter or fresh meat, but vodka is still plentiful. No one has a job. Or a car. But when one of a sextet friend group gets enough money to buy one, these tight buddies take an odyssey from Łódź to the Baltic Sea.

It’s a fantastic short to watch on the big screen, utilising a minimalist black-and-white hand-drawn style with acres of empty space, honing in on the specifics while stressing the scarcity that scarred the nation during this time of deep austerity. Kowalska is constantly playing with the limits of the frame, sometimes zooming in on just a face or a car, or presenting us with a powerful panorama, such as the Baltic Sea, offering the possibility of leaving Poland for good. Complimented by a dreamy 80s score, all drum machines and synths, The Car presents a finely-wrought evocation of a time characterised by hardship, yet ultimately defined by hope.

It serves as the perfect prelude to the animated competition winner Pelikan Blue (László Csáki, 2023), which is the kind of animation/documentary hybrid that seems to perfectly capture the spirit of DOK Leipzig’s programming ambitions. Based on archive audio collected from 2011-2021, the film satisfies two of my favourite interests: nerdy train stuff and oral history.

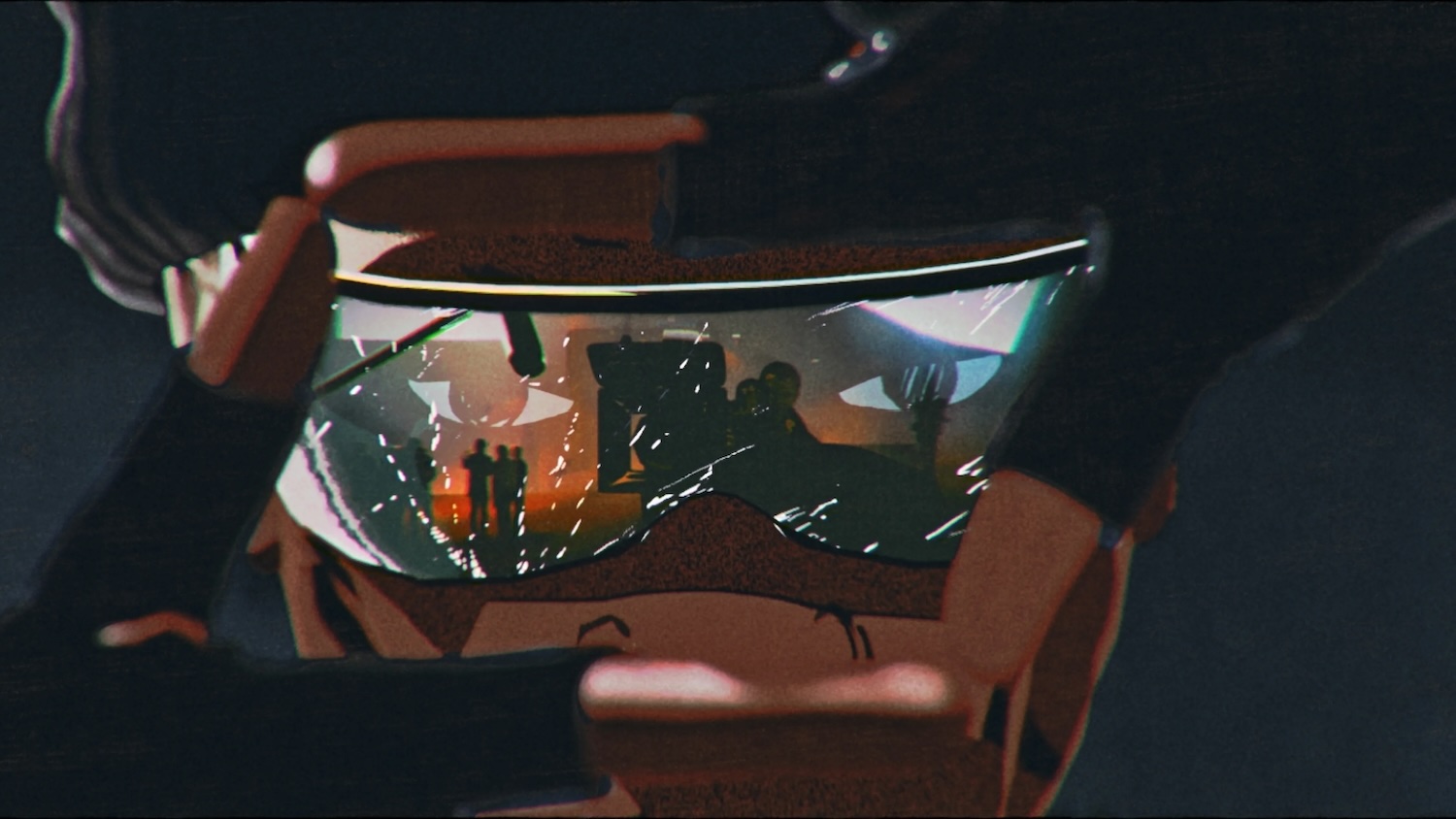

The year is 1990. Finally freed from the horrors of communism, Hungarians are now able to travel to Western Europe. The only catch: they can’t afford it. But three friends have the novel idea of forging international train tickets. The trick is buying a domestic ticket before using the newly available Domestos (a neat metaphor for the possibilities of capitalism) to bleach off the handwritten journey, allowing them to forge wild adventures, taking in Stockholm, London, Rome, Madrid, and beyond. The eponymous Pelikan Blue refers to the only ink that bleached off properly, enabling these men to travel across the entirety of Western Europe for free. But naturally, the scheme gets out of hand, with more and more people wanting to leave Hungary, bringing in detectives and the spectre of extended prison time.

But as one of the men recalls his mother telling him, “Stealing from a man is a crime, but stealing from the state is glorious,” reflecting the resourcefulness Hungarians grew up under during the socialist era and which spilt over during its capitalist transformation. And they never actually used these tickets in Hungary itself! Any loss was incurred by Western nations, perhaps doubling up as a metaphor for how Hungary organised itself under Orban to use EU funds for the personal enrichment of its oligarch class.

It’s shot in a blocky animation style, with clear and defined lines and emotive characterisation. Sometimes Super8 footage is used for quick inserts, reminding us of the historical reality of the story and imbuing it with an added sense of urgency. But there is also a playfulness here, including a ludicrously exaggerated French inspector known as the Clown, presented like the villain in a Hanna-Barbera cartoon. Capturing bygone eras filled with both possibilities and paranoia, both Pelikan Blue and The Car startle with their complete lack of contemporary cynicism.

Male Anxieties

The second pairing of short + feature was the animation competition entry The Brown Dog (Nadia Hallgren, Jamie-James Medina, 2024) followed by the documentary competition film Luciano (Manuel Besedovsky, 2024). Besides vague questions about male identity and belonging, I couldn’t quite map the connection between the two films as well as in the last programme.

The Brown Dog is perhaps most notable for being perhaps the last credit by The Wire (David Simon, 2002-2008) legend Michael K. Williams. He voices a security guard working for an anonymous apartment block, driven crazy by the tedium of his job while wondering if the world even cares about low-wage workers. (To drive the point home, his jacket reads NOBODY.) Powered by a graphic novel-esque aesthetic, romantic noirish colours, and various pained observations about the world around him, the short animation does a great job of building up a convincing atmosphere but never feels compelling beyond generalised Joker-style male angst.

A far better depiction of male anxiety, whether economic, social or gender-based, comes in the form of the Argentine Luciano, a tender and observational depiction of the trans male experience that runs a little on the slow side but mostly works thanks to its hard-won compassion and close observation of the ins and outs of living your truth in the rough-and-tumble barrios of Rosario.

In the Q&A, Besedovsky stated that he wanted to focus more on Luciano’s economic reality — hustling to make ends meet, working as a bricklayer, finishing high school in his 30s, handing out CVs — than his transness, choosing to reveal it at the end. But as the film progressed, it became obvious that this trans perspective simply had to be told.

Things that cisgender men might never think about suddenly become fraught with fascinating questions. What’s it like to go to a club and flirt with cisgender women? What do you do when you head to the male toilet and there’s nowhere to sit? What is showering in the gym like? And what does it mean to be a man but still be capable of giving birth?

It’s also notable that as the online world continues its heated debates about what a man is or what a woman is or whatever, when it comes to Luciano’s everyday life, his male friends are completely relaxed about his gender identity, consciously holding space to let him express himself, making this film a necessary antidote to the insanity of everyday conversation.

Besedovsky constantly lets scenes play out longer than convention may dictate, including two startling, standout sequences: one where Luciano recounts police brutality and another where his mother mourns the so-called death of her daughter. I also appreciated the scenes with his trans girlfriend, who irittatingly flits in and out of the film despite the usefulness of her perspective. But these are few and far between in a documentary that is happy to meander when a tighter focus is demanded. It lies in the editing, such as the same back-of-head shot of the protagonist walking through his neighbourhood that bookmarks the film. Of course, you work with what you have, but it’s annoying when such powerful material feels buried underneath unnecessarily slow filmmaking choices.

Visiting a film festival during its last weekend can often be an odd experience. By the time I turned up at DOK Leipzig, the industry portion was already over. The staff looked tired, although upbeat and friendly. I even saw posters and banners being torn down as I left the cinema for the last time. Luciano didn’t feel like the last film of a festival, but a frustrating interlude before the real good stuff. Still, I have to end it here. It is enough.

Read part one here.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.