Yerevan is not an easy place to get to. One missed connection and everything can go wrong.

Just as I passed a breezy (too breezy) security control in Berlin, the worst happened. Like a gut punch to the stomach, a text from Eurowings: my flight to Vienna (where I would be catching an onward flight) was cancelled. Several frantic (and expensive) hours of rebooking and travelling through Warsaw followed; my final 11 pm flight a chaotic mess of babies crying, attendants loudly hawking 1 am perfumes and bright, sleep-abolishing lights. By the time I got to the airport — 4:30 in the morning — everything felt strange and unreal.

It was a LOT.

Despite the early hours, the airport was alive. Some kind of international celebrity (or very rich man at his bachelor party) arrived, greeted by a gaggle of busy women in sailor outfits, evoking the fantasies of Leonardo DiCaprio in Catch Me If You Can (Steven Spielberg, 2002) before they chaperoned him to his limousine.

And in the short taxi from the airport to the hotel, several strip clubs — including the instantly striking Burlesque, with a building-sized Eiffel Tower — remained open for business. Yet despite the preponderance of garish scenes, there was also a certain beauty in uncovering a new city in the early hours of the morning; a pink sunrise forming over the river, buildings and distant mountains. Yerevan had already weaved its special charm.

A Long Day at the Factory

Regional competition entry Orbita, viewed at the Cinema House, is a very rough-and-ready documentary, featuring unvarnished digital camerawork, with a tendency to blur the image through excessive zooms, and filled with unflattering close-ups of mouths and eyes. Yet its triumph doesn’t come through the simple style but Vardanyan’s ability to be a true fly-on-the-wall, letting the camera run and run and run to uncover deep and bitter truths about its subjects.

Aside from a framing device in a car on either side of the film, Orbita takes place almost entirely in a former Soviet munitions factory. It’s seriously delipitated, with paint peeling off the walls, chipped wood and broken concrete, cobwebs of broken wires and crushed desks. But one floor is still operational, with a group of men hard at work creating backgammon sets.

At first, it appears that Vardanyan is making a process movie; filled with drilling, whirring, and careful chipping of wood to make these functional works of art, yet as Orbita progresses, it moves into a moving exploration of the psychological effects of the second Artsakh war.

Things take a turn once the backgammon sets are put aside and the men retire to the smoking room for drinks. With no women around, the conversation turns to war, to lost relatives, to living under the current Armenian reality. Heavy dialogue about orphaned children mixes with stupid games, excessive inebriation, drug taking and un-PC phone clips, Orbita showing us a very masculine approach to processing trauma. What it lacks in conventional style, it more than makes up for in raw, emotional honesty.

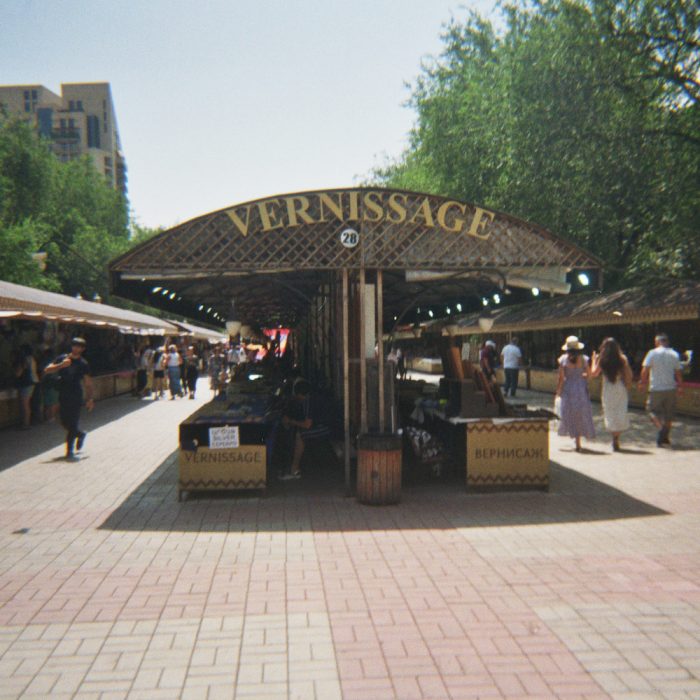

Almost identical backgammon sets are on sale at the nearby Vernissage, a large open-air market that also sells rugs, clay pots, mastrushka dolls, oil paintings and various other arts and crafts and bric-a-brac. I even saw a group of men playing a game to pass the time between customers.

Inspired to make my soon-to-be-occupied new flat in Berlin feel more homely, I bought a rug with a pomegranate design and a small painting of an eggplant. Then it was off to the grand Moscow Kino, built in 1936 by the Soviets, for Ararat.

The Mythical Mountain

Ararat is said to be the most mythologised mountain in the world. It is where Noah’s Ark was supposed to have ended up; it adorns an eponymous brandy and cigarette packets. For the Armenian people, the mountain, visible from parts of Yerevan itself, is a central symbol of the nation as a whole. It’s even on their coat of arms.

But Armenians need a visa to see it up close. It’s in Turkey.

Before 1915, two million Armenians lived in eastern Turkey, where they were Turkish citizens. But the forced deportation and mass murder by the Turks (estimated to be anywhere between 664,000 to one point two million people), has brought that number to almost zero. Ararat is not only a symbol of pride, but a symbol of lost hope. Of trauma.

In Ararat, David Alpay plays the Armenian-Canadian Raffi, on his way back from a trip to eastern Turkey to photograph the mountain. He is stopped by a soon-to-be-retired customs agent (Christopher Plummer) who interrogates him about the nature of his journey as well as a suspicious-looking film canister.

This framing device powers the rest of the film, which explores Raffi’s involvement with the production of a film about the genocide, directed by the esteemed Edward Saroyan (Charles Aznavour) with input from his own historian mother (Arsinée Khanjian). Weaving the difficulty of depicting this trauma with the story of expressionist painter and genocide survivor Arshile Gorky (Simon Abkarian), as well as a complicated familial backstory (involving murder and suicide and an odd step-sister-step-brother relationship), Ararat is a convoluted yet intermittently touching work from the famed Armenian-Canadian director.

The film was met with bafflement and derision upon its Cannes release (although it won at the second edition of the Golden Apricot itself). You can see why. The framing device, the intersecting narratives, the non-linear storytelling; it’s a difficult and opaque viewing, avoiding a conventional telling of trauma in favour of a complicated dance around the subject.

But like the also heavily metafictional Aurora’s Sunrise (Inna Sahakyan, 2022), Ararat lays clear the difficulties of displaying a truth that has been so heavily (and perhaps successfully) denied. After all, it’s not only the Turks that are in denial. My own country, the UK, doesn’t recognise it either.

These attitudes lead to widespread ignorance about the suffering of the Armenian people. Arguably, it makes the events in Karabakh, shockingly undercovered in Western media, easier for the Azerbaijani government to facilitate. As Egoyan himself said in the introduction, the film feels more relevant today, as the last two years have re-opened old wounds.

Yet its stylistic leaps, its flat moments and the weird cheapness of the film-within-the-film, make it harder to appreciate aesthetically. Even with that stacked cast (Aznavour, Plummer, Greenwood, Bogosian, Khanjian), Ararat pales in comparison to Egoyan’s best work. Importance doesn’t equal quality.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.