Limbo is the new film by Ivan Sen. It’s not to be confused with Limbo (Ben Sharrock, 2020), Limbo (Soi Cheang, 2021), Limbo (John Sayles, 1999) and Limbo (Tina Krause, 1999). But it feels fresher than its unoriginal title suggests, using the desert noir genre to explore the history of racial oppression in the Australian outback.

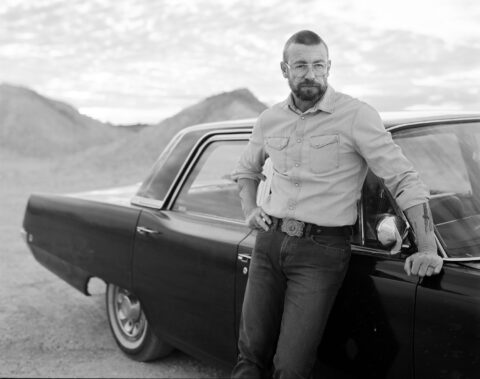

Simon Baker, seriously underacting, stars as a detective tasked with cracking a cold case in the Australian outback. He’s staying in the appropriately titled Limbo Motel, a cave-like dwelling with no other inhabitants. Seeking redemption for a failed relationship in the past, he listens to a preacher on the radio, talking about how with God, the negative can be turned into positive. Limbo diligently explores this thesis.

Using a desert aesthetic that can only be described as black-and-white Breaking Bad (Simon Baker also looks like Bryan Cranston), Limbo often feels like an austere TV series condensed into cinematic form. We see sweeping panoramas of the desert, abutted by the arrival of a car or Western-style mining town buildings. Locals searching for opal in the dirt. Abandoned dogs and broken down cars. It’s all very moody, bringing to mind both True Detective (Nic Pizzolatto, 2014-19) and Top of the Lake (Jane Campion, 2013-2017).

He drives from place to place, reluctantly conducting a review of a case of a missing aboriginal girl 20 years after the fact. The locals, naturally, are reluctant to talk; the mystery as deep and hidden as the caves that provide an appropriate metaphor for submerged secrets.

While the detective story is engaging, the film is less interested in collecting clues than the idea of exploring an indigenous culture broken by colonialism. We learn that when a white child goes missing, the police bring in the choppers. When a black child goes missing, they sit on their behinds and twiddle their thumbs. It’s great that Australia is having these conversations through genre films.

Slowly but surely he is tasked with bringing a fractured family together, the film carefully avoiding white saviour tropes in favour of something far more touching and universal. I could expect a moderate streaming success.

The biggest problem is that Limbo, nowhere near big enough to merit Competition, is a little too sleek and handsome; unwilling to go deeper into the tortured psychology of its characters. It just feels incomplete. A more expansive TV format would’ve been more appropriate.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.