Nuri Bilge Ceylan is basically a 19th-century Russian novelist.

I don’t mean literally — literally speaking, he is a 21st-century Turkish filmmaker, and a rather cinematic one at that, setting his protagonists against the immense harshness of Anatolian plains — but metaphorically; in theme, pacing and even shot composition. I would argue that more than any other contemporary filmmaker, his works evoke the existential inquiry and philosophical tone of the 19th-century novel, especially the Golden Age of Russian literature. Plus, simply watching the films feels like reading an epic novel — loads and loads of subtitled text over nearly three and a half hours that probably adds up to over 50,000 words. No one else, at least outside of his imitators in Turkey, is doing this.

His latest, About Dry Grasses (2023), starring Deniz Celiloglu as a petty “intellectual” serving out the end of his mandatory teaching post in a perenially-snowed-under East Turkish village, is both a sweeping epic — endless man vs. nature shots — and an intimate character study, his hero the very definition of a superfluous man — trying to exist outside of the system while seemingly trapped within a vast, complicated and often corrupt bureaucratic world.

The superfluous man, an amorphous, far-reaching term, can be applied to many types of Russian Byron-inspired heroes. As Kelly Hamren writes:

“The superfluous man is the dual product of Russian culture and Western education, a man of exceptional intelligence who is increasingly and painfully aware of his failure to synthesize knowledge and experience into lasting values, whose false dignity is continually undermined by contact with Russian reality, and whose growing alienation from self and others leads to an unabashed exhibition of and indulgence in cowardly, ludicrous, and sometimes destructive instincts.”

It certainly applies to 19th-century Russia, but perhaps it applies to modern-day Turkey as well. After all, both Russia and Turkey are diverse, authoritarian nations, with complicated, long-simmering colonial projects, caught (literally and metaphorically) between East and West. And the situation in modern Turkey, filled with obligatory postings to diverse regions with their own unique cultural traditions — an entire genre upon itself, as also seen in Emin Alper’s Burning Days (2022) — brings to mind not only Russian but also British and French colonial literature, with men barely hiding their contempt for those they have been charged with uplifting. It’s fertile ground for a highly literary type of cinema with one eye towards the future of the nation and another endlessly looking back — showing the secular dream of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (silently featuring alongside Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in portraits throughout About Dry Grasses) stuck in a never-ending sectarian past.

Confusing his “civilised” city roots with moral and intellectual superiority over his village students and contemporaries, Samet at once seeks to find answers to his existential condition while barely containing his inner toxicity. As my contributor Jenny S.Li so elegantly put it in her Cannes review:

“Ceylan’s patient storytelling, framed within his still photography style, allows the audience to thoroughly witness the fall of Samet’s façade. The audience sees not simply why Samet is toxic, but also how this toxicity corrodes his own being.”

Considering himself apart from political and social norms, while adhering to a narcissistic, nihilist outlook, he brings to mind Grigory Alexandrovich Pechorin in Mikhail Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time (1840), a self-serving, Byronic hero, filled with self-importance-and-barely concealed racist loathing, using women as a means to fill his own existential void. But in Russian literature, the joke is often on the hero, with Ceylan also using his characteristic humour and dramatic flair (heavily inspired by Chekov) to undercut Semet’s self-importance.

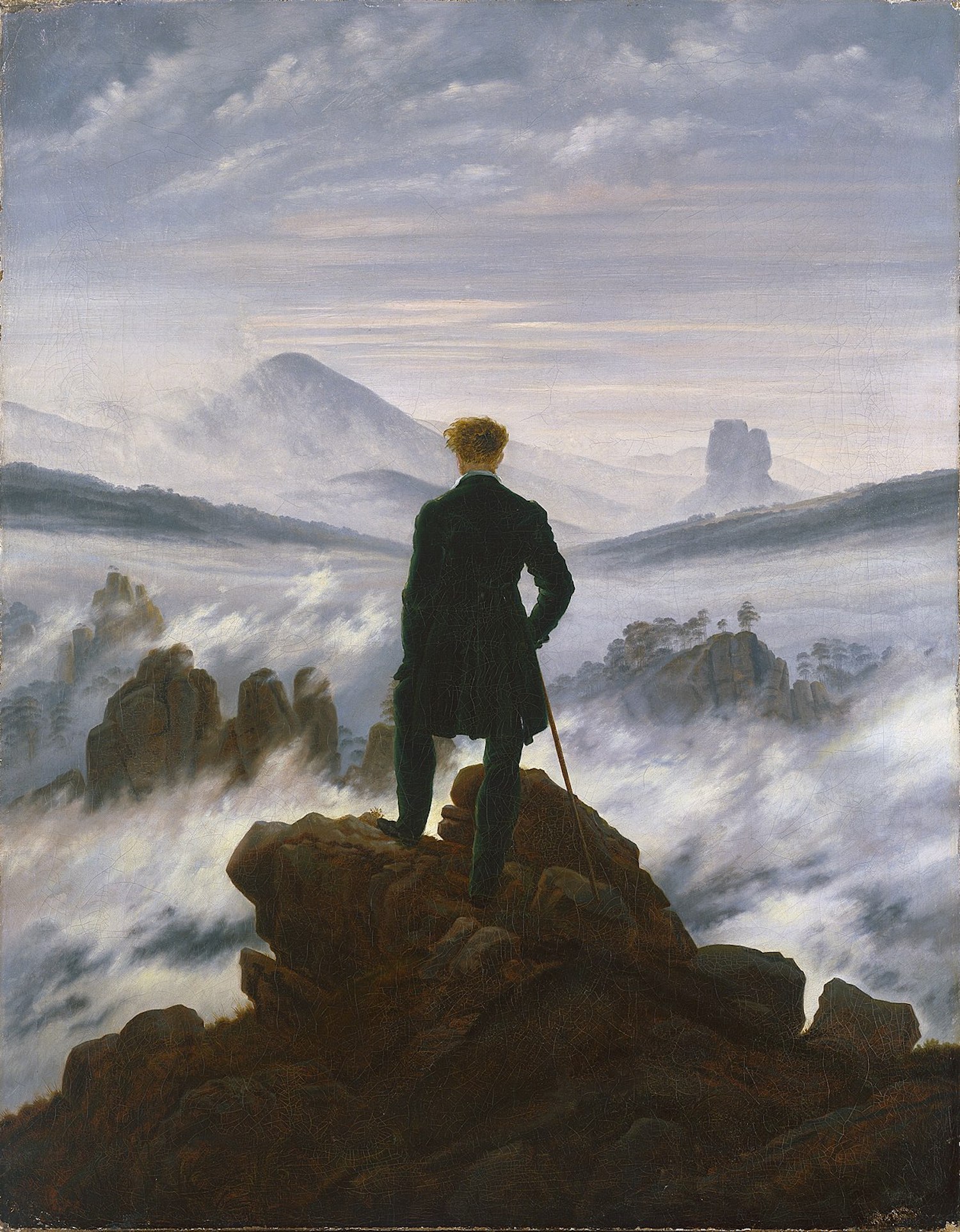

Ceylan, working with cinematographers Kürşat Üresin and Cevahir Şahin, makes these Byronic comparisons rather obvious, evoking Germanic romantic paintings, such as Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (Caspar David Friedrich, 1818, below), when framing Samet against the wider landscape. But it’s not so much how Ceylan views Samet as how Samet mythologises himself; especially when compared to Samet’s own pictures, fetishising the locals instead of ever properly getting to know them. (At one point, those images even get distorted, in a bizarre dream sequence, and morph into uncanny AI — Samet’s artistic yearnings slowly turning into a tragic nightmare.)

What makes this film so satisfying is how closely the screenplay, written alongside wife Ebru Ceylan and Akın Aksu, hews to Samet’s perspective, even giving him the last lines, as he fixates on one of his students and argues that she held the key to him surviving a dreadful winter far from home. It’s a bold choice from the Turkish auteur, getting us inside our protagonist’s point-of-view, even if he is literally one of the most petty and awful people to ever be committed to film. It’s an emotional maturity otherwise lacking in contemporary cinema, but common to the complicated heroes of Russia’s 19th century; guys like Goncharov’s Oblomov, Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov, Tolstoy’s Levin or Turgenev’s Bazarov.

It’s especially gratifying when Napoleon (Ridley Scott, 2023), focussing on the defining figure of the 19th-century — one who makes an indelible impression in War and Peace (1869), both as a tyrant and undercut as an ultimately inconsequential man, and serves as an inspiration for Raskolnikov’s axe-murderings in Crime in Punishment (1866) — was so poorly rendered by the lacklustre Joaquin Phoenix. One could imagine a superior Ceylan/Celiloglu version already. Just picture it: snow-capped battlefields, with each drop of snow expertly rendered in hyper-HD digital cinematography (that isn’t super grey), epic panoramas and long drawn-out, passive-aggressive conversations about movements on the battlefield — all the while Napoleon, a self-serving man, is also worried that Josephine is cheating on him once again.

I would caveat this piece with the acknowledgement that my knowledge of Turkish literary tradition is extremely slight (OK, non-existent) and surely has its own inspiration here, yet given Ceylan’s acknowledgement of classic Russian literature in interviews (including a desire to make Dostoevsky’s Demons [1871-2]!), it certainly appears to heavily weigh on his work. Capping off his trilogy of obstinate assholes (alongside Winter Sleep [2014] and The Wild Pear Tree [2018]) with an even worse kind of guy than before, About Dry Grasses keeps the spirit of 19th-century Russian literature alive, one insufferable, pompous blowhard at a time.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.