With 31 films from 36 countries, Panorama is a very wide-reaching section, taking audiences around the world from the comfort of the cinema screen. It’s a broad and diverse tent, with a focus on audience engagement (with audience prizes!) while portraying the limits of human extremity. Politics! Sexuality! Romance! Thrillers! It sounds exciting, but the surprises come hand-in-hand with the snoozes. And while this edition has had some solid efforts, it sadly can’t be called a vintage year.

Going for the heart more than the head (unlike Forum, which goes for the head and steadfastly avoids the heart), Panorama is also home to the internationally respected Teddy Award, awarded to the best queer film. We’re providing short and sweet reviews for as many of these films as we can, especially as this section is strangely underserved by press screenings during the festival proper. For some films, we also have longer stand-alone reviews. This list will be regularly updated throughout the festival.

Crossing by Levan Akin (2024) — Opening Film

Let’s be real — aside from the big Sundance films and a few gems sprinkled about, the Panorama slate this year is pretty weak. Thankfully, Crossing, Levan Akin’s follow-up to Cannes hit And Then We Danced (2019), makes a solid choice for the opening night film.

It’s a thrilling, thoroughly modern and deeply human drama about looking for someone who may not want to be found.

The first ten seconds sum up its main character perfectly — a Georgian woman in her 60s with a striking face walks by a river. She carries a determined look that says, “Don’t fuck with me. I am on a mission.”

This is Lia (Mzia Arabuli), a retired schoolteacher who travels to Istanbul with her scruffy young neighbour Achi (Lucas Kankava) in search of Tekla, her transgender niece who seems to have disappeared. The bulk of the film combines this mismatched fish-out-of-water theme with a missing person setup with ease.

Istanbul emerges as a character. Akin explores the city’s vibrant chaos while diving into the complexities of Lia and Achi’s evolving relationship, where jaded wisdom clashes with youthful defiance. Arabuli is a constant joy to watch; her interactions with Lucas Kankava’s Achi are both humorous and prickly, illustrating the unpredictable friendship that can blossom under extraordinary circumstances.

Although there’s this urgent business of finding Lia’s niece that’s the film’s central mystery, Crossing has a freewheeling, laidback vibe, allowing both main characters to become sidetracked with minor subplots that further reveal more of their interior worlds.

Crossing’s exceptional camerawork often uses roving, fluid shots to explore spaces, like early on when Lia first goes to Achi’s house. It’s a hostile situation, and the camera heightens the tension by slowly circling the dwelling in a 360° movement. Shortly after when the two take a boat ride, the camera zooms forward all over the ship, surveying the entire vessel and all its travellers.

It communicates one of the film’s recurring themes: for one reason or another, human beings are always on the move. The camera then does this cool pan up trick from a ship balcony to introduce a new trans character called Evrim (played by trans actress Deniz Dumanlı).

Akin clearly got the memo on how to write about a trans person who functions as more than just a symbol of transness. Evrim is a fully fleshed out and empowered character who’s out there standing on business, navigating hostile bureaucracy and working at a job that allows her to advocate for her marginalised community. Other developments in Evrim’s arc drive home the message: trans women can have it all, including romance. They don’t have to be constantly portrayed as victims without agency.

Written by Jared Abbott

Meanwhile on Earth by Jérémy Clapin (2024)

You don’t need a huge budget to create a good science-fiction film, but it does depend on what you want to say. Trying to show us the vastness and mysteriousness of space through animated sequences in an otherwise live-action film can work when your film is a riot of formal invention, but when you’re a European co-production, it’s obvious that you don’t have the budget to actually build a spaceship.

Thankfully, when Meanwhile On Earth isn’t animating space, it spends its live-action portion… Anyway, this film is really bad; grasping at magic and meaning and profundity, with Hans Zimmer-esque rising arpeggios and bravura camera compositions and crying and screaming scenes, but lacking any detail — narrative, emotional, cinematic — to make us actually care about what’s going on.

A short-changed Megan Northam stars as Elsa. Her brother is gone and she can’t let it go. He was a cosmonaut sent on a dangerous mission before mysteriously disappearing. Me you and everyone you know know aliens are involved, but it takes 25 minutes of Elsa being sad before it is finally confirmed, with a mysterious link established between our world and the next. Soon Elsa is forced into some weird alien stuff and it was really hard for me to care what happened next.

With a super–epic widescreen frame, Clapin uses Power Shots continuously: big close-ups and inserts, huge panoramic landscapes, drone shots, slow zooms, reverse zooms, et. al. It has the impression of severity, but little emotional impact. It just feels weak. It doesn’t help that Elsa has little interiority beyond, “I draw things and want my brother back.” Considering I rather enjoyed his previous film, the completely animated I Lost My Body (2019), perhaps Clapin could’ve made this film as a full cartoon work. This slice of science-dysfunction was completely lost on me.

Written by Redmond Bacon

The Visitor by Bruce LaBruce (2024)

Bruce LaBruce’s decision to update Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema (1968) for the modern-day is brave. The Visitor follows in the original’s footsteps: a wealthy family takes in a stranger who quickly seduces every member. Here LaBruce replaces the Milanese estate with a modern London manor.

As we watch the visitor (Bishop Black) emerge from the suitcase on the bank of the Thames, a voiceover offers a speech more absurd than the visuals before us. To British audiences, the insipid racism from Katie Hopkins, Boris Johnson, and other politicians is all too familiar. Paired with watching a Black man stroll through London stark naked, we are reminded of how commonplace racist rhetoric is in British society, and how Blackness is perceived as a threat due to the insidious bigotry of the upper class.

But The Visitor’s powerful beginning does little to save it from mediocrity. Once inside the house, The Visitor quickly descends into a John Waters imitation without the exuberant camp execution. The posh Brits are performed as messy drag caricatures that do not pass as the elites they represent. Their sexual liberation is therefore inevitable; the bourgeois fog lifted by the visitor’s presence was clearly never really there.

The direct sex scenes continue on with inevitability: Yes the sexual partners are diverse, but the scenes fail to succeed in their attempts at attracting the viewer. The wooden-clothed performances do not lure us into the explicit scenes before us. The phrases urging for revolution, such as “EAT OUT THE RICH,” are meaningless statements that fail to inspire action.

In many ways, The Visitor is too literal in its expressions of its manifesto to be taken as more than an explicit musing. Watching the father (Macklin Kowal) aggressively thrust at the sculpted fallen letters that spell out “CAPITALISM” is no replacement for the real-world implications of Teorema’s patriarchal figure lording over his factory. In order to urge the audience towards a sexual revolution, they must feel seduced. The Visitor only succeeds in mocking Teorema’s existential awakening rather than recapturing it.

Written by Billie Walker

Faruk by Aslı Özge (2024)

A meandering metafiction, Faruk nails the theory but falters in the praxis. Rich in ideas about gentrification, bureaucracy and the corruption at the heart of the Turkish construction industry, its self-reflexive and middling tone undercuts the true power of its satire.

Özge casts her father as the hero. Faruk is a 90-year-old man, living in an apartment block in Istanbul, earmarked for demolition. Bigger, glassier, yuppier and more expensive flats await. The film betrays its hybrid approach from the start, Aslı herself giving her father directions on how to act better: especially as he interacts with the other members of the building, looking to cut a deal with snakey, shady developers.

The sheer corruption involved in the plan is shocking, but in light of last year’s devastating earthquakes, unsurprising. To get public funds, they must deem the building unsafe, even though it is safe. And the building plans submitted are different to the building in actuality: for example, what’s written to the government as a mosque is actually going to be a gym.

The only man who stands in their way is the funny, irascible Faruk. His character feels complex and multi-layered, probably because he’s had 90 years to prepare for his first-ever role. But while this metafictional layer works as character detail, the extra baggage — boom mics in the frame, clapboards, take after take — do little to enhance this story of municipal corruption.

Still, the last scene is a doozy, finding a fun way to square the metafictional ouroboros. It perfectly satisfies the deep irony at the heart of the project. I just wished the rest of the film was as bitterly cutting.

Written by RB

I’m Not Everything I Want To Be by Klára Tasovská (2024)

The documentary I’m Not Everything I Want To Be follows the early years, career triumphs, pitfalls, loves and losses of Libuše Jarcovjáková, the Czechoslovakian photographer whose political and artistic tenacity earned her comparisons to Nan Goldin. What ensues is a montage of photography and narration from the excerpts of her diary.

For the audience, Jarcovjáková’s story begins at the age of 16, in Prague 1968, when she first picks up the camera. The tool that will help her discover her politics, her friends and lovers. When Libuše Jarcovjáková decides on her artistic form, photography, all else follows.

However, Libuše must convince the rest of the world about her passion. The university deems her not working class enough. To be accepted, she decides to curate the authentic working-class individual they are searching for. But she finds something truer than the romanticised image of struggle they seek.

However, she must apply thrice before the university deems her worthy of attending. This assertion is a constant in her life. In many bids to escape the oppressive reality she experiences in Prague, she leaves her home for her husband’s home; for Japan and for Berlin. While her social standing and her experience of the “normalisation” period in Prague, puts her at odds with the capitalist world she often finds herself in, her class “authenticity” is something she is forced to prove.

Her brusque style of photography matches her blunt narration. There is no attempt to distort the truth of her life or avoid the often dark realities she finds herself in. But amongst the mental troughs, the loneliness, the financial struggles, there is joy. Libuše is at home with many people across the world. In these moments of hedonism, Klára Tasovská’s direction becomes artfully apparent. The pace of photography changes and the scenes dance as if they were more than stills.

Just as life is expansive, so is I’m Not Everything I Want To Be. In search for herself, Jarcovjáková discovers life beyond communism, the creative pitfalls of commercialism, her own changing body, and sexual exploration. Thanks to her diary entries, which flow naturally as if narrated for the documentary, we are privileged to peek at a political and creative life well lived.

Written by BW

Andrea Gets a Divorce by Josef Hader (2024)

“I want an amicable divorce,” says the eponymous Andrea (Birgit Minichmayr) of Andrea Gets a Divorce, a film about a police officer called Andrea who never gets her divorce and leads a life that is far from amicable. But she does end things with her husband. By accidentally running him over and killing him, before cowardly hiding from the scene of the crime.

Set in the far east of Austria, near St. Polton, it’s an oddball comedy about a woman who is perpetually stuck in a really shitty situation. And due to some stubbornness on her part, an overall deadpan feeling of bleak yet amusing sadness, and a screenplay that adheres firmly to everyone-is-a-moron territory. It’s a weak cinematic project that would perform better as an original Fernseher film, especially as mildly amusing counterprogramming to the endless number of Krimis on both German and Austrian television.

Germans will probably disagree. My screening compatriots seemed to find this particular strain of Austrian comedy funny in much the same way British people might find Irish comedies funny: they speak the language differently, they’re prone to strange, rambling anecdotes and every second person appears to be a farmer. And there’s a bit of Martin McDonagh in the way Andrea’s partner (Thomas Schubert, climbing all the way down from Afire [Christian Petzold, 2023]) says that this is a town where the “women are moving away and the men are getting weirder.” All they are missing is a priest.

But the issue isn’t the sociological detail, which can be amusing — from the farmer who accidentally lets his cows die, to the man refusing to let the cops do a gun check, to the lecherous and racist lads in the pub — but the pacing of the project. This type of film is rich in comic and ironic potential, but popular Austrian comedian Josef Hader — who gives himself the worst role — can’t build any of his scenes to a meaningful climax. It’s like Andrea’s fucked up car. Stop and start. A busted engine.

Written by RB

Paradises of Diane by Carmen Jaquier and Jan Gassmann (2024)

The magic of the movies lies in the ability to offer alternative realities; a safe space to engage in far-fetched ideas. Many people may dream of simply sacking it all off and moving to a new place, but few have the chutzpah of Diane (Dorothée de Koon). Shortly after giving birth — in a raw, intimate scene with uncomfortable close-ups of her vagina — she leaves the hospital room, walks down the street and boards a long-distance coach from Switzerland to Benidorm.

It’s a clean break. When her husband calls her, she buries the phone in the ground.

And the southern Spanish city is a whole new world. Bright lights, neon bar signs, leering, drunk British expats. Diane is both bothered and bewildered, but bewitchment is hard to come by.

Reeling both physically and mentally from post-partum depression, she holds cold cans of beer against her bare breasts, still heavy with milk. Jaquier and Gassmann have an eye for the physicality of femininity, carefully mapping and photographing Diane’s body — naked, vulnerable and deeply alone. Ready to start afresh. Tentatively.

But this is less a paradise than purgatory, a limbo state hovering between different models of feminine independence.

Some narrative steam kicks in when she strikes up a friendship with the older Rose (Aurore Clément), another estranged French-speaking woman who lives in a high apartment block overlooking a mysterious island. She is witty (asked what she does, she says “I smoke”) and wise, telling Diane: “If we opened people up we’d find landscapes inside.”

Yet inside Rose is a slowly emptying void, constantly forgetful due to a deteriorating mental condition. Perhaps her vulnerability reminds her of Diane’s own child, crying and alone, unable to care for itself. While her emotions are physical, Diane’s more existential, her fate contrasted powerfully against the rush of the sea, the pretty city lights, the pulse of the night.

Diane’s interiority is never presented, yet newcomer de Koon finds a subtle, micro-expressive acting style — observing, silently reacting — to suggest landscapes of inner turmoil. Taking us into bizarre territory that lands with the force of truth, Paradises of Diane is a finely rendered portrait of revolt against femininity.

I appreciated its careful feeling, de Koon’s sensitive performance and its unflinching willingness to tackle, like The Lost Daughter (Maggie Gyllenhaal, 2021), one of the last remaining no-gos of the modern Western woman.

Written by RB

My New Friends by André Téchiné (2024)

Whether it’s Les Misérables (Victor Hugo, 1862, innumerable adaptations), La Haine (Mathieu Kassovitz) or Lupin (George Kay, François Uzan, 2021-) on Netflix, the French have always been obsessed with the eternal conflict between criminals and law enforcement in upholding the true spirit of La République. Enter My New Friends, which complicates the conflict between Jean Valjean and Inspector Javert by having the police officer hate her job and the criminal a nice man who lives just next door.

Isabelle Huppert stars as Lucie, a reluctant police officer still reeling from the death of her partner — both in enforcement and in love. We first meet her at a Blue Lives protest, singing La Marseilleise while admonishing the state not to do enough to protect police lives. As her partner committed suicide after their dereliction of care, her relationship with the institution is at an all-time low. So when a young lovely couple move in (Hafsia Herzi and Nahuel Pérez Biscayart), she keeps her career under wraps. She simply doesn’t want to identify as a cop anymore. This is complicated when the husband, Yann, is revealed to be a member of a radical anti-capitalist group.

There’s a lot of fertile ground for conflict here, yet Téchiné’s style (shaky camera movements, awkward inserts, descriptive rather than evocative voiceover) undercuts any sense of tension.

Engaging in an “idiot plot” trope (where the film would be over if someone just told the truth) can be perfect in a thriller. We can wonder how far she might go to contain her secret and how morally grey the so-called binary lines between the proud police officers and the ACAB crowd can truly be. Nonetheless, like his similarly tepid radicalism narrative Farewell to the Night (2019), My New Friends fails to meaningfully develop this central conflict, failing to split the difference between lived-in characters and a genuine moral dilemma.

Endless scenes of Isabelle Huppert on her daily jog, or her ex-husband’s bizarre sartorial choices, add to a bathetic feeling. When the riot police turned up, I silently cheered them on. Probably not the emotion Téchiné intended.

Written by RB

Memories of a Burning Body by Antonella Sudasassi Furniss (2024)

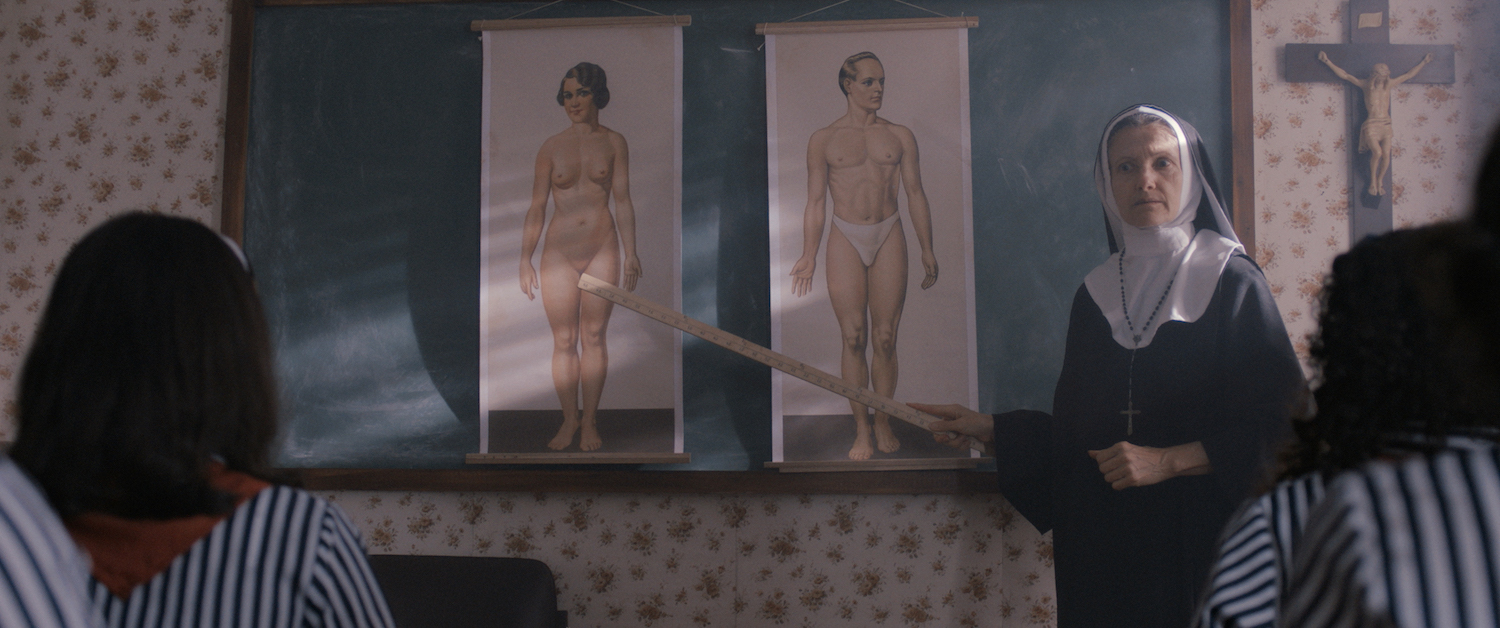

Although we think of ourselves as a sexually liberated society, we still limit the lives of our older citizens. For instance, the sexual accounts of women are most often told by the young. However, Antonella Sudasassi Furniss’ Memories of a Burning Body defies this pattern. Her subjects break taboos surrounding age and gender, speaking from the unique perspective of those raised in a repressive time.

Using the conversations she had with Ana (68), Patricia (69) and Mayela (71), a fragmented history of the body is formed, one with hidden desires, passion and pain. In order to protect the accounts of the omnipresent voices that fill each scene, the audience is offered one woman per each vital stage of their sexual biography: a child (Juliana Filloy), a young woman (Paulina Bernini), a woman (Sol Carballo).

Antonella Sudasassi Furniss’ film is one that defies genre. It may begin with a break in the fourth wall and define itself as biography, but the scenes of dramatisation have more life than the clinical recreations that documentaries have accustomed us to. Much like the body hums with electricity and changes pace, ever-present (for better or worse) till its last beat, this film has an organic pulse.

Memories of a Burning Body features many vivacious reenactments that paint the picture of the repressed lives of Costa Rican women who have adhered to societal expectations only to be punished for complying. But the moments which feel the most emotionally explosive are when Sol Carballo retraces a memory as she paces through her now quiet home. These moments demonstrate how the past is repeated in our bodies and how the cage of the flesh doesn’t represent the passionate depths of our desires.

Many incidents of sexual assault and domestic violence become apparent at different stages in the conversation. While survivors’ stories are often told in the immediate aftermath, by speaking to these women in later life, distance and retrospection offers some clarity. Through Memories of a Burning Body, the audience is privy to comprehensive sexual biographies which have been defined by societal pressures and systemic violence, but most importantly the precious intimate expressions of desire by these three women.

Written by BW

Scorched Earth by Thomas Arslan (2024, feature image)

As all freelancers know, the work is the easy part. The hard part is getting paid. You think magazines are bad? This difficulty is exponentially increased when you’re a professional criminal.

Thomas Arslan returns to the hard-boiled world of Trojan (Mišel Matičević) and his dodgy associates with this excellent sequel to In the Shadows (2010) — a film I will certainly be checking out once the Berlinale chaos is over. Recalling the stripped-back style of Jean-Pierre Melville, the film (working perfectly as a standalone entry) reminds us that the coolest criminals are always the calm ones.

Matičević shows why he’s one of Germany’s best crime actors with a deeply guarded performance, playing a man who’s been a professional far too long to get played. In an excellent opening gambit, he steals watches from a house in Essen. It’s a simple job. But when it comes to the handover, his client attempts to stiff him. He manages to get away, but the job remains unpaid. Any professional writer can relate.

This short sequence is Scorched Earth in miniature. But the central Berlin heist ups the stakes considerably. The target isn’t watches, but a Caspar David Friedrich painting. Ironic, considering his deeply romantic style is the complete tonal opposite of Arslan’s aesthetic.

The archetypes are all in place: the last-job-guy, the getaway driver (Marie Leuenberger), the hacker, the fixer hiding behind a professional seeming job and the evil bastard (Alexander Fehling) who wants to make everything worse. But more exciting genre pleasures are to be found in the observational, highly controlled style of the job itself, Arslan getting us down to the absolute bare essentials. When the job is this satisfying, nothing more is needed.

Sometimes it’s so hard-boiled that it becomes overcooked, with little life allowed to stream out of its deeply compressed tone. Especially, as the heist was so tightly controlled, the chaotic aftermath could’ve allowed more looseness in style. Yet the little glimpses we see of Trojan’s dreams, reveal a simple and melancholic life, especially when he rejects getting to know his associates more than he absolutely has to.

It’s touching and sad. Like many freelancers, his work is his entire life. Payment will be made, one way or another.

Scorched Earth tactics.

Written by RB

Rising Up at Night by Nelson Makengo (2024)

During a sermon, words of preaching and truthful ‘light’ searching resonate in the pitch black of the opening screen in Nelson Makengo’s debut feature Rising Up At Night (2024).

When the first images start unveiling, it is still dark, our eyes struggling to adapt to the handful of battery-powered torches illuminating unclear shapes and helping us navigate unfamiliar surroundings. A few canoes are cruising through flooded streets, in a seemingly post-apocalyptic setting that feels terribly real.

This is the life Kinshasa’s inhabitants have been living for four months now, one of constant struggle for access to lighting and coping with periodic inundations. No government support is expected anytime soon after an election period that has threatened its already precarious political and economic stability. As news from the radio briefs us on the current, uncertain state of Congo’s Inga III power stations project, which could provide electric supply to a large swathe of the continent, Makengo’s dimly lit yet overly fictionalised images paint a picture of a city plunged into constant darkness. All the while, snippets of conversations, instants of life and hazy bits of information are pieced together to reveal a tenacious community resourcefully fighting back.

Aided by a (sometimes too) intrusive score and by a combination of erratic handheld camerawork and lyrical static shots, Makengo’s collage of struggle and resistance illuminates the artificially lit authentic existence of people working together to preserve what is left amidst the uncertainty of tomorrow, finding strength in commonality as much as in God’s blessing. Faith is deemed the only guiding light to cling to, a ritualistic combination of immediate necessity and yearned epiphanies invading all aspects of daily life, blurring the line between illuminated salvation and darkly harsh reality.

The contested beauty of Kinshasa at night is also at the core of Makengo’s tale of survival. Guided through an unfinished geography of noise, obscurity and mud, we mentally reconstruct the capital in its unlivability and shared sense of hope. Dispersed majestic views of the city from above appear as the only moments of quietness, pondering instants where the camera takes a breath before deep diving again into the wild midst of plagued yet joyfully bursting life.

Between scattered lights and flickering hopes, we are left with the wondering feeling of what remains to fight for. In the end, Makengo seems to suggest, a new day commences, and life moves on. So do the brave people of Kinshasa, who are defying the darkness enveloping their nation by finding their own light.

Written by Massimo Iannetti

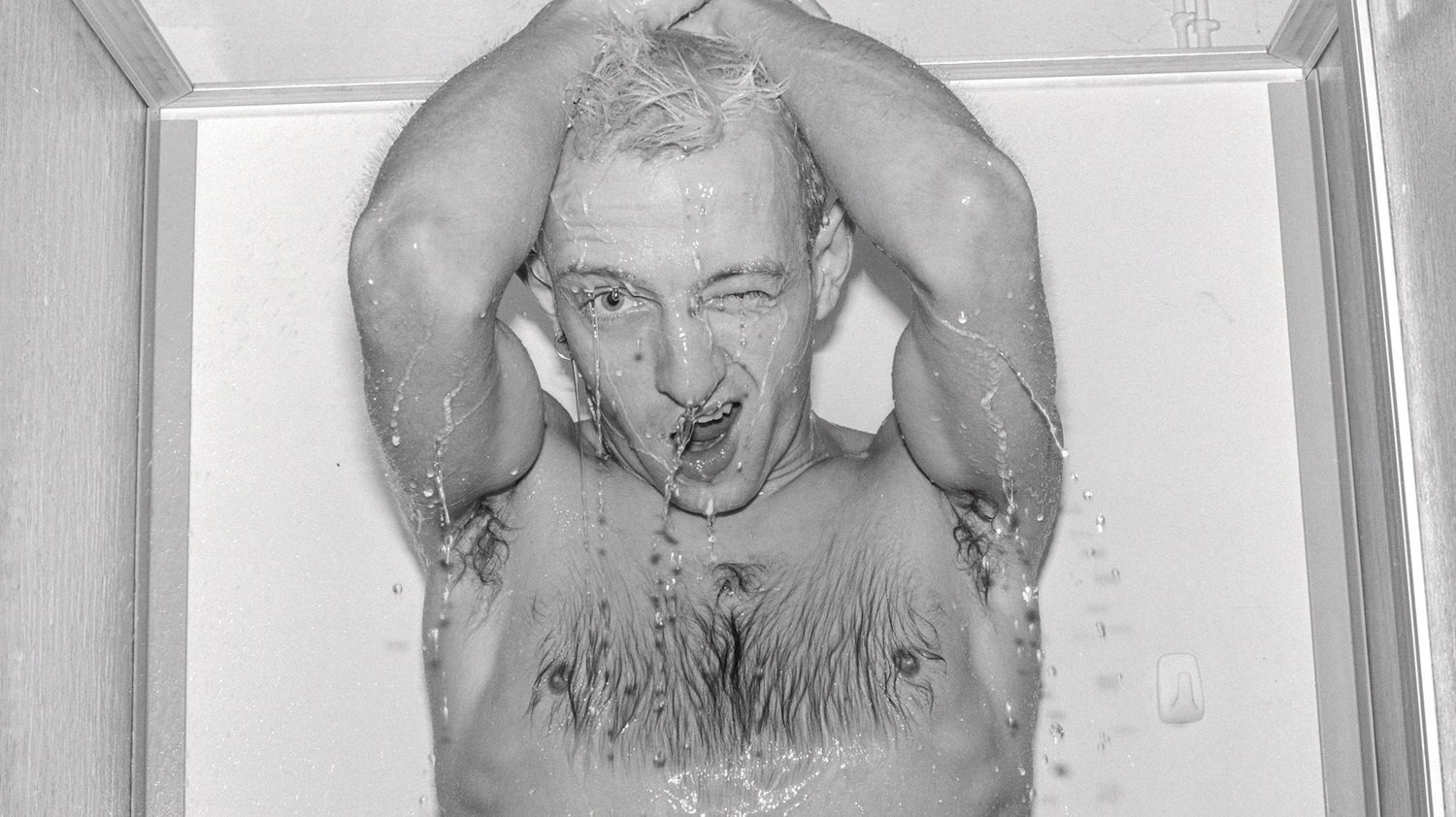

Baldiga: Unlocked Heart by Markus Stein (2024)

Like any great artist, Jürgen Baldiga’s photographs are instantly recognisable.

Intimate black-and-white portraits of himself and other queer people, sex workers, and folks living on the margins of society, Baldiga’s work not only chronicles the West Berlin queer scene in the 80s as it was overtaken by the AIDS crisis but also his final years as he succumbed to the virus. Markus Stein’s Baldiga – Unlocked Heart blends hundreds of photos and videos with reenactments, diary entries, and interviews to create a hybrid documentary that also serves as a companion piece to Rettet das Feuer, Jasco Viefhues 2019 film that also examines Baldiga’s legacy and body of work.

Baldiga: Unlocked Heart is impressively assembled and bold in its presentation of the artist’s work, sexuality and experiences with HIV (and its hybrid style with cold and clinical reenactments feels current), but it often fails to provide the contextual information that would fully submerge viewers who are not familiar with Berlin’s 80s queer scene. It assumes a certain amount of prior knowledge and leaves the viewer feeling as if they are missing essential pieces of the puzzle.

Narrative diary entries give insight into both the artist’s personality and his transition from sex worker to photographer/painter/poet/activist, but if you are looking for a more comprehensive portrait of the West Berlin scene, you should probably check out Rettet Das Feuer instead.

Although Viefhues’ film is far less concerned with style — it’s clearly low-budget and does not introduce anything new in form or aesthetics — it has a much more intimate approach to storytelling. You come away with a better understanding of how the artist’s death impacted his inner circle as well as the community at large. Friends and lovers sift through Baldiga’s archive, gossiping and offering amusing anecdotes over coffee and cake, resulting in a more warm and informative piece.

Baldiga: Unlocked Heart also avoids discussing how Baldiga ended his life. For a film that has no problem zeroing in on all the suffering that comes along with the final stages of HIV/AIDS — at one point a whole list of virus-related ailments are listed off — there’s a strange reluctance to discuss his actual passing and the network of care that made it a little less frightening.

Written by JA