I remember that brief time I was taught film theory at boarding school. I think, for some reason, it was part of my English GCSE. I learned about close-ups, crane shots and panning from Roland Emmerich’s The Day After Tomorrow (2004).

For a snob, it might be a strange choice of film, yet Emmerich is unafraid to mix and match different shots and techniques to tell a cohesive story, making it a rather instructive illustration of form.

(Another contributing factor for that particular selection might’ve been the sudden and very pressing concern around the environment — I was forced to watch An Inconvenient Truth [Davis Guggenheim, 2006] on at least three separate occasions.)

It was only in my sixth-form years that I took a serious interest in cinema. Someone shared Goodfellas (Martin Scorsese, 1990) over the LAN. I watched Ingmar Bergman movies, buffering very slowly over YouTube. Through these more traditional choices (no offence Emmerich!), it became obvious that cinema was the most powerful and direct art form of them all.

While my private school was a bounty of privilege, offering a media studies class at Sixth Form (I didn’t take it. I was more interested in books at 16), most don’t offer film classes at all. And despite cinema forming our common cultural language, it certainly isn’t a part of the obligatory curriculum. The documentary Subject: Filmmaking (Edgar Reitz, 2024) is great evidence that it should be.

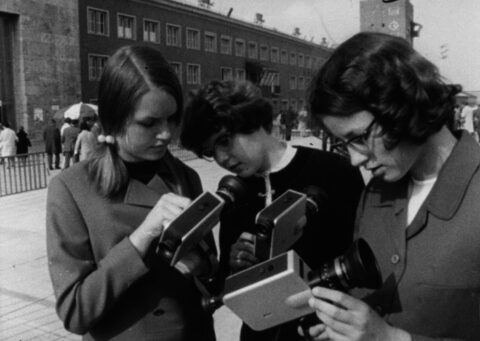

In 1968, Reitz, a signatory on the Oberhausen Manifesto (associated with the famous motto “Papa’s cinema is dead” and the birth of German auteur cinema) and the acclaimed director of Mahlzeiten (1967), had a novel idea: the teaching of film, already established at his adult school in Ulm, to a group of 13-and-14-year-old girls at the Munich Luisengymnasium. He believed (and still believes) quite strongly that film was a universal language; the teaching of it a powerful tool for unlocking the creativity and imagination of children.

The result was Filmstunde (Film Lesson), released on Bavarian television in 1969. 55 years later, the director bumps into one of his old students, surprised and delighted to know that several of the girls, now old ladies, have been holding regular Stammtischen (regular informal meetups) ever since. For the updated Filmstunde_23 (presented in English as Subject: Filmmaking), the 90-year-old director regathers his former students to discuss how his temporary course transformed these young girls’ lives.

The best, most delightful moments come from the screening of the student films themselves.

Some are fantasies: dressing dolls up and contrasting them against arabesque backgrounds or the whimsical tale of a boy who can wish for absolutely anything, his desires immediately granted by the snap of his fingers and a quick film cut.

Others are strict documentaries, transformed by time into vital historical archive: a remarkable look at an old-fashioned printing press; the characters at a Munich market; the famous Russian hermit Father Timofey building his own church in what’s now Olympiapark.

Some are harder to classify, like an angry look at police officers, shot in a mixture of slow-motion and time-lapse video, or a football reportage that later became an influence on Hellmuth Costard’s experimental George Best portrait Football As Never Before (1971).

But what’s immediately evident is that, given a Super 16 camera and an encouraging, patient teacher, children can express themselves in endlessly fascinating ways.

In fact, these girls show more innovation and style than a sizable amount of the other directors at this year’s Berlinale. I’d happily sit through all 26 of these shorts in a row.

As the films are shown, the women often narrate, giving extra details about their lives at the time and how Reitz’ patient and curious teaching approach liberated them from the stuffy confines of late 60s Bavaria. They also reflect on how their relationship with cinema changed as a result of this class. Surely we should all be given the tools to think so critically about the images we all see on such a regular basis.

What’s remarkable is how consistent the personality types seem, evoking the key thesis of Michael Apted’s Up Series (1964-), to “Give me a child until he is seven and I will give you the man.” While probably nowhere near as dense as Reitz’ 59-and-a-half-hour Heimat series (1984-2013, I’ll get around to it one day!), it collapses decades of history in just a simple and affecting cut.

Edgar Reitz, receiving the Berlinale Camera Award this year, seems to love cinema as much as when he first started making movies over 70 years ago; with so much love lavished on the ageing Scorsese these days, the ongoing and unwavering dedication from Reitz is also worth noting.

Now with every young person owning a film device in their pocket, perhaps the lessons of Subject: Filmmaking — which looks very much at what happened when girls got their hands on then-expensive film equipment — seem quaint. Yet, the idea of twinning creativity with formal education, taught by filmmakers themselves as they look for funding for new projects, still seems utterly tantalising.

Let’s just hope, that if this does become law (whether in Germany, the UK or somewhere else), kids can learn from slightly more inspiring films than The Day After Tomorrow. I mean: at least put on Independence Day (Roland Emmerich, 1996).

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.