Whenever there is a Hungarian party at a film festival, goulash is not very far behind.

Sadly, I was too busy feasting on endless amounts of Slănină (cured slabs of fatback) to join the queue. By the time I got there, it was gone. Earlier in the day, I purchased some Palenet cu cartofi for around 5 lei (one euro), which is basically a pastry filled with potatoes. I reminded me a little of Russian pirozhok, but much bigger. For meat and bread lovers, you can’t do much better than Transylvanian cuisine.

After the Hungarian party, I walked to another party, past the main square, where hundreds of people were both in the open-air screening and standing just outside, watching Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942) weave its timeless spell. In a moment of pure film-watching serendipity, I stopped just in time to watch La Marseillaise sequence. Vive la France!

Thankfully, excellent food (and too much wine, hence the late post) was not the only nourishment found at TIFF today. The two documentaries I saw in the What’s Up Doc? section, concerning themselves with questions of dedication and the use of one’s available free time, were also excellent.

Folly or Genius?

Everyone has heard of the Sagrada Família in Barcelona, devised by Antoni Gaudí in the late 19th century yet still unfinished to this very day. Even in its unfinished state, it is a highly impressive work of architecture and a living testament to the combination of faith, commitment and art. But according to Don Justo, who has spent the last 60 years of his life, working away on a cathedral of his own, Gaudi is “absolute garbage”. Just wait till you hear his opinions on Picasso!

Working away, ten hours a day, six days a week, in the outskirts of Madrid, in the municipality of Mejorada del Campo, the former monk turned self-proclaimed architect/engineer/builder is excellently surveyed by Denis Dobrovoda in The Cathedral (2022, above). Mixing together reams of archive footage, including personal video diaries and TV documentaries, and combining it with new footage of Don Justo in the last years of his life, it gets deep into his motivations for making this building all by himself with all types of novel materials, as well as elegantly outlining the unique structures of this remarkable marvel of engineering, all created by one man doing whatever he can to build a shrine to God.

He’s certainly a unique type of religious devotee, the type that you don’t see so much depicted in cinema, as his aim is not fame or reward, but simply doing everything he can, mostly by himself, to dedicate his life to God. But he is far from an austere character, oftentimes chuckling and smiling as he goes about his work, usually without any kind of harness or helmet or safety protection, becoming more and more irascible as the footage moves from the 90s to the present day.

While railing against the modern world, he is also filled with humorous paradoxes — like praying for grace after watching football matches but still ardently supporting Real Madrid. Becoming more frail in his last years, accompanied by his key helper, Angel, he never loses his way with words, including a few hilarious insults for the tourists who deem to take a picture of him at work. He’s simply a great character, which is often half the battle in making an engaging documentary.

And the final cathedral, still being built today, is truly one of the great examples of outsider or folk art, Don Justo using whatever materials are at hand to create his ramshackle, put-together building, including an incredibly novel use of tennis balls, Of course there are imperfections, and numerous violations of conventional building codes, but it turns out that the building is actually structurally sound, with no reported injuries. I couldn’t imagine this happening in the UK. Anglicans don’t have any imagination.

Artificial or Reality?

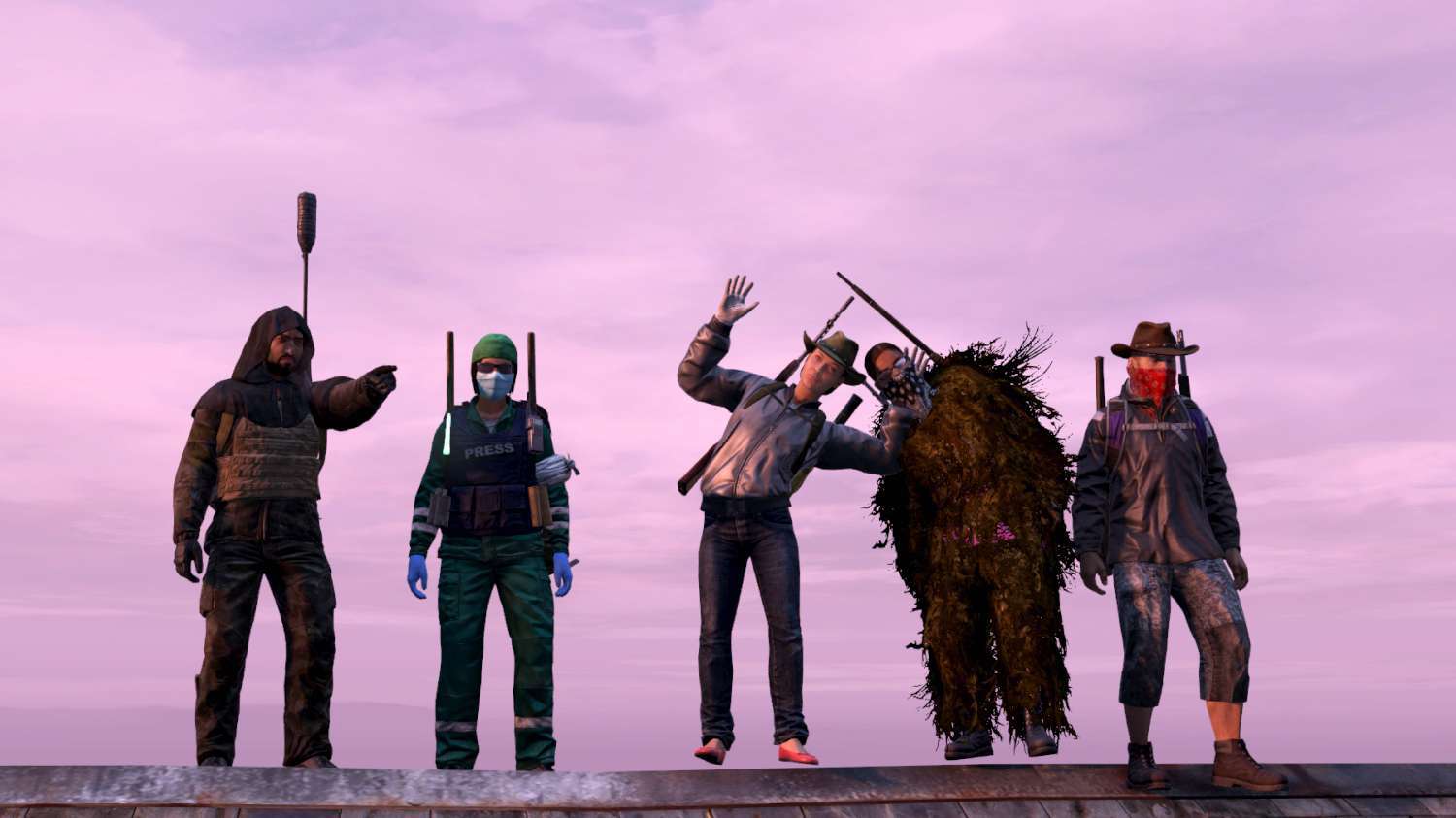

According to the producer, Knit’s Island (Ekiem Barbier, Guilhem Causse, Quentin L’Helgouac’h, 2023) is the first feature-length documentary to be set entirely within the world of a video game. A contemplative, peaceful, highly immersive film that benefits massively from the sanctity and size of a cinema screen, it’s both a fascinating exploration of the relationship between the real and the virtual world, as well as an aesthetically engaging exploitation of the inner beauty of open-world video games.

We never see the three filmmakers in the film. Instead, we are joined by their avatars who function as an online film crew. With 250 square kilometers to work in, the game, DayZ, mixing the rainy countryside with Eastern European aesthetics — orthodox churches, abandoned buildings — is a massive sandbox where you can choose your own way of playing. While there are some zombies that are easily killed, they are not the main focus of the survival game: with no conventional narrative, one can choose to either form a group and work together, become a farmer, or kill anyone who gets in your way. You can even make a movie.

Knit’s Island follows these filmmakers as they look for people to talk to, spanning from young girls simply playing for fun, to older people whose busy daytime lives cause them to dive into the game as a means of escape. Remarkably mature and thoughtful about their decisions to play, to choose characters outside of the usual realm of knowledge, to do things they would never consider in real life, Knit’s Folly gets great mileage out of simply letting them talk and tell us about their lives, the deep emotion of their stories often bizarrely contrasting against the emotionlessness expression of the avatars.

It compares favourably with the work of Austrian film collective Total Refusal, whose short video game films, subvert the aims of Red Dead Redemption 2 and Battlefield to make us look at them in a new way while also reflecting on the world outside the game. But this filmmaking crew lack the stated Marxist aims of Total Refusal, preferring to find those moments of strange beauty and serenity that make certain video games so relaxing and meaningful to so many people.

My only real complaint comes right at the end, when the hermetically sealed world of the film is broken in favour of a banal lockdown comment. I can understand why it was included, but it undoes a little bit of the power of imagining people’s lives behind the screen by simply showing it to us instead. If it ended with the excellent scene before, mixing profoundity with humour by showing us something deep that is also a glitch, it would’ve been perfect.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.