An Iranian fable in Canadian climes, Universal Language (Matthew Rankin, 2024) both befuddles and impresses, superimposing disparate cultures in an intellectual, disorienting stew. It’s easy to appreciate on an aesthetic and cultural level. It’s harder to love on a subjective, emotional level.

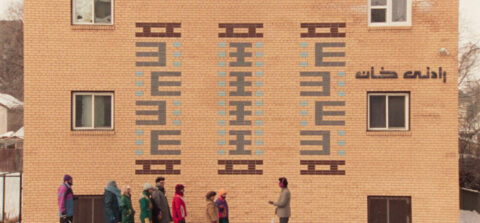

It’s set in Winnipeg — modernist, alienating, snow-laden — but not as you know it. Imagine that Iranians colonised the North American nation instead of the English, and you’d have some idea of Rankin’s surrealist aesthetic. Signs are in Farsi, walnut vendors roam the streets and the vast majority of actors are from an Iranian background.

(Perhaps Canadian nationalists, if they ever sat down to watch some arthouse cinema, might be outraged to find that even Tim Horton’s — Canada’s most famous coffee and doughnuts chain — has been transformed into a Persian teahouse! Having never tasted Horton’s coffee, I can’t say if this is a genuine improvement.)

Rankin goes deeper than mere surrealism, following up his history-debut The Twentieth Century (2019) by weaving in an alternative reality of the wider province of Manitoba. For one thing, the Canadian dollar has been replaced with the Riel, named after the French-Métis resistance leader Louis Riel (1844-1885). This combination of alternative history with pure fantasy is a heady and powerful mix, giving way to an uncanny world where everything feels familiar but also profoundly different.

Tellingly, Quebec is still Quebec, a proud French-speaking province! Our protagonist, Matthew (Matthew Rankin), leaves his administrative job in their government to head to Winnipeg to locate his mother, eventually coming into contact with two children, Negin (Rojina Esmaeili) and Nazgol (Saba Vahedyousefi) on a mission to extricate a trapped Riel note from the ice. And just as cultures clash, these two stories interweave in odd ways, Rankin engaging in circular narrative tricks to obfuscate the simplicity at the heart of his story.

Rankin excels at world-building, from the beige-coloured buildings to the endless hostile traffic of a typical North American city — with funerals punctuated by the sound of passing trucks and motorbikes — to the lovingly-crafted, Kaurismäki-esque production design; forbidding clerks in tiny kiosks, carefully organised stores (including one dedicated entirely to Kleenex) and even Iranian-style propaganda posters. But these beguiling and comic visuals are undercut by an emotionally wanting tale, unable to corral his withdrawn protagonists into a deeply felt story. Everything points to a touching, oddball tale of cultural and personal identity, but something kept me at a distance throughout. Building a world is easy; taking it apart and showing why it matters is the more difficult task of art.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.