Last night, I ate at the Stadtwächter (City Guard), a traditional German joint with a wide selection of schnitzel dishes. Mine was named Erichs Leibling (Eric’s Darling) and came with a fried egg on top and a huge heaping of creamed mushrooms and pommes frites. Afterwards, I was treated to a complimentary Eierlikör (Egg Liquor) presented in a tiny ice cream cone. Particularly of note is its location, located in the Medieval city walls, with the upper half of the cosy tavern integrated within a tower.

This is the small, compact Cottbus old town, built as a gord (fortified Slavonic settlement) by the Wends in the 10th century. And at the other end of the traditional city walls lies the Sprembergerturm (Spremberger Tower), dating back to the 13th century. It rings every 15 minutes and measures 28 metres high. I paid two euros for the privilege of climbing the tower today, but my view, as in Armenia, was obscured by a dense thicket of fog.

Despite such tribulations, images of Medieval times briefly flashed through my mind: the vast migration of people groups, cumbersome toll booths and customs, skirmishing tribes and the spectre of invasion, disease and death. The clash of ideals. Civilisations.

On Moonless Ground

If New Zealand suddenly becomes too expensive or their government stops giving tax breaks to Hollywood, perhaps Kazakhstan — currently maligned in the Western imagination by Disclaimer (Alfonso Cuarón, 2024) star Sacha Baron Cohen — could step in as the new playground for international fantasy cinema. With its vast steppes, impressive mountain ranges and rough-hewn ground, plentiful horses and deep tradition, it feels like the natural setting for the next instalment of The Lord of the Rings.

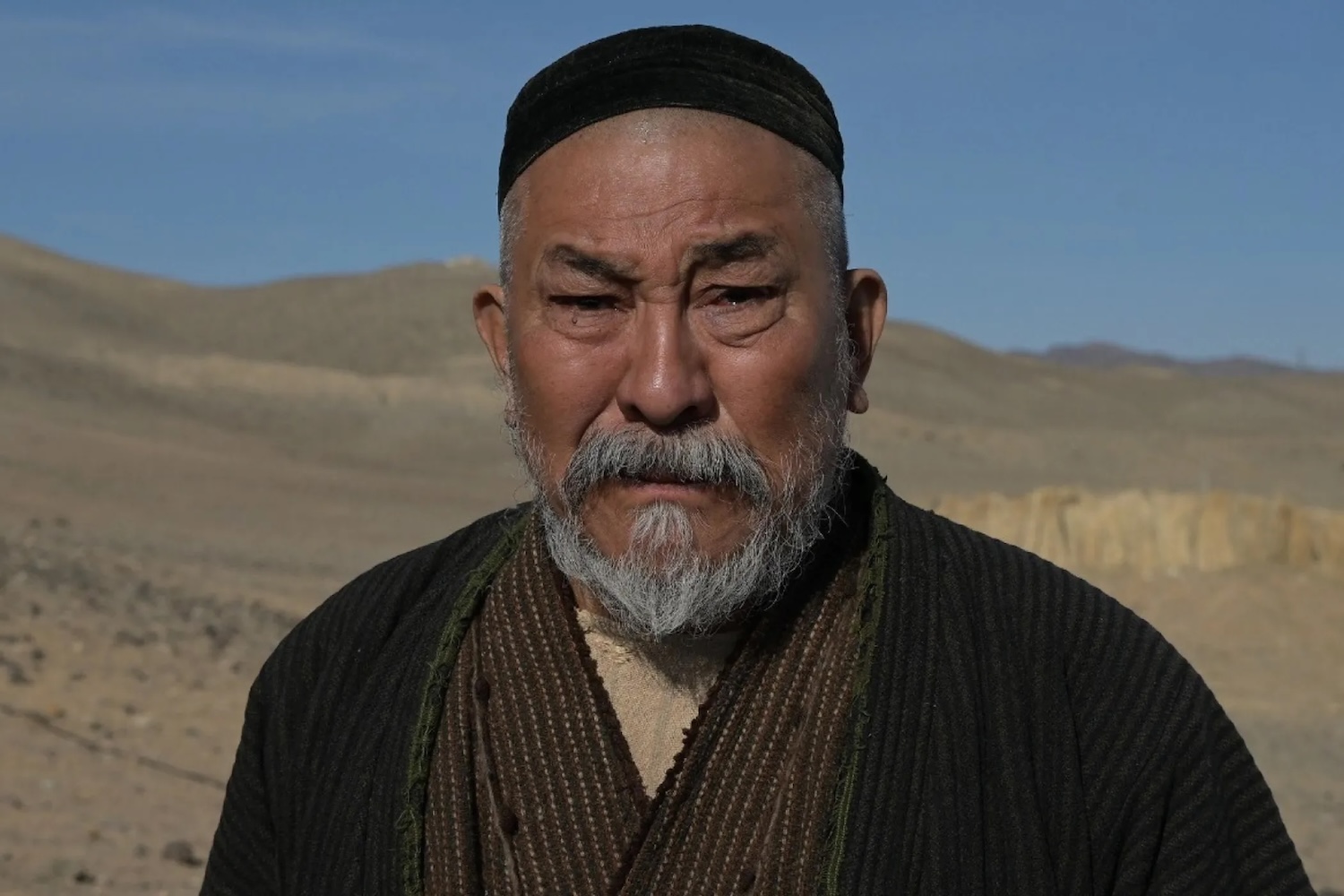

Playing in the Midnight Madness section at the Gladhouse, Tamás Tóth’s 2023 picture Oliara (translating roughly to moonlessness, referring to the perpetually grey skies of the Kazakh steppes) specifically evokes the Rohan sections of The Two Towers (Peter Jackson, 2002), with its depiction of horse-based people fleeing an invading force, while also following the classic structure of a white-man-finally-joins-the-rebels narrative.

Dances with Wolves (Kevin Costner, 1990), Avatar (James Cameron, 2009) or On Deadly Ground (Steven Seagal, 1994) might come to mind, but the closest comparison is probably The Beast (Kevin Reynolds, 1988), the underrated cult classic about a Soviet tank commander who joins forces with the Mujahideen during the invasion of Afghanistan. Like The Beast, Oliara, set in the early days of the communist revolution, is also about the limits and devastation of the Russian imperial project, one that unfortunately continues to this day.

But Tóth’s film is noteworthy for how his protagonist, the Hungarian István Magyar (Péter Bárnai), working as a commissioner tasked with herding up the local’s livestock, isn’t a particularly useful rebel, standing helplessly by as his contemporaries commit various war crimes. And the enemy isn’t Russians themselves, but Kazakh stewards of the Leninist project, inflecting famine and abuse on their own people to forward the delusion of communism. But in the end, Magyar (whose name literally means Hungarian) recognises a common bond between himself and the local people — perhaps a potential shared Turkic ancestry? — forcing him to finally do the right thing.

The problem is that you can see all of these developments coming from the very beginning, with an honourable intention — paying tribute to the 1.3 million Kazakhs who died of famine due to Soviet farming policies — but a tepid structure. Occasionally, the veteran Tóth, trained in Moscow at the esteemed Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography, finds a powerful image, our hero in the foreground, the dead being buried behind him, or a particularly textured image filled with rain or sleet or fog, but for the most part, the execution is rather pedestrian, lacking the flair that a truly effective Western needs. For a far, far better version of a Kazakh Eastern, shot with real comic timing worthy of Leone, I’d recommend checking out Goliath (Adilkhan Yerzhanov, 2022) instead.

Let’s Cook Lithuanian

It was a bad idea to skip lunch to watch Spectrum entry Tasty (Eglė Vertelytė, 2024), also in the Gladhouse, which offers a veritable feast of classic Lithuanian dishes, from Cepelinai (potato dumplings) to Kugelis (potato pudding) to various ways of cooking a herring. The only thing they didn’t seem to include is Šaltibarščiai, a bright pink cold beetroot soup beloved across the Baltics. Either way, it had me craving something — anything — with potatoes in it.

A comic tale rooted in national pride, Tasty traces the journey of two close friends who work in a Kaunas-based canteen, serving traditional food to working-class folk: lorry drivers, construction workers, factory employees. In an early scene, Saulé (Agnieška Ravdo) and Ona (Elena Ozari) are working on a curd cheese recipe, caught from above, experimenting with replacing meat in their Cepelinais. It costs more than meat, yet it’s a success, offering an early glimpse of these two girls’ innovative culinary techniques.

Dreaming of a life above their station, Saulé enters the two friends into a cooking competition entitled Let’s Cook Lithuanian. Lying about their provenance, changing the name of their canteen Gardutė (Tasty) to the French-sounding La Gardutė and making up a story about training in France, these humble working-class gals are pitted against the top chefs in the country, learning a lot about themselves and the nature of showbusiness in the process; think UnREAL (Marti Noxon Sarah, Gertrude Shapiro, 2015-2018) meets Chef (Jon Favreau, 2015).

The screenplay feels especially workshopped and pored over, with each scene providing a particular beat or shading in another character’s motivation or pulling back the rug to provide us with another twist or comic moment. As a result, I was unsurprised to check Vertelytė’s Instagram page and see she also works as a screenplay consultant. This strong writing is also complimented by solid filmmaking chops, from a satisfying tracking shot taking us into the studio for the first time to whip pans to a comic smash cut.

Its tight structure and broad reach make this film the only selection from the entirety of this weekend that could conceivably enjoy a wide-ish release and be a modest financial success.

But I was left wanting more. A cooking movie is not just a series of pleasing dishes one after another but should have some kind of showstopping centrepiece as its finale. It doesn’t have to be the Timpano from Big Night (Stanley Tucci, 1996), but it should at least be something that makes the viewer sit up and stand in awe. Cepelinai sure looks tasty but feels too modest. Maybe some variation of Šaltibarščiai, with its vivid and startling colour, could’ve been just the ticket.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.