With a whopping 34 films this year, Panorama is by far the biggest and meatiest section of the Berlinale. With a strong audience focus and a lack of press screenings during the festival itself, it’s also the most oriented towards the general public, something which is reflected in the more populist parts of the programming as well as the audience award. We’ve tried to watch as many Panorama films as we can, which you can check out below. Additionally, check out our standalone reviews for Deaf (Eva Libertad, 2025), Peter Hujar’s Day (Ira Sachs, 2025), Night Stage (Marcio Reolon, Filipe Matzembacher, 2025), The Good Sister (Sara Miro Fischer, 2025) and Home Sweet Home (Frelle Petersen, 2025).

Delicious by Nele Mueller-Stöfen (2025)

Saltburn (Emerald Fennell, 2023) for Erasmus students, this extremely generic Netflix Original (unnecessary drone shots, lame EDM cover versions of popular songs, easily digestible conflict, lots of sex but no actual eroticism, “provocations” that are simply icky, EU English, fake twists) spits out yet another variation of the trendy “Eat the Rich” genre, taking a thuddingly literal approach to its tired class analysis. This movie doesn’t need Berlinale, it’ll be in your “Top 10” on March 7th. Best paired with IG reels.

By Redmond Bacon

Dreams in Nightmares by Shatara Michelle Ford (2024)

The road trip might be the most flexible genre of all. All the characters have to do is go from A to B. The rest of the premise is an open canvas for filmmakers to do as they please, making broad statements to reflect on the state of the nation and the infinity of the human soul.

Even so, Dreams in Nightmares (Shatara Michelle Ford, 2024, feature) stretches the road trip genre to full malleability. Using the genre to create a hybrid seminar slash meditation on what it means to be Black and a woman and Queer in the USA today, its anything-goes approach is oddly compelling even as the film lacks even the notion of an idea of a plot.

It starts with Z (Denée Benton) losing her job as a creative writing professor, prompting her to visit her friends Tasha (Sasha Compère) and Lauren (Dezi Bing) in Brooklyn. They go out, get drunk and hook up with strangers before heading off on a road trip across America to find their long-lost college friend who has mysteriously cut off communication. Using Yelp as their Green Book, they navigate themselves, America and their own sexuality, resulting in a film that is continously compelling, even when it lags in tempo.

Those who fully subscribe to the “no hugging, no learning” school of comedy should look away now. There is a lot of cringe-worthy language and moments here, especially as Z interacts with her painfully perfect boyfriend (Charlie Barnett), outdoing Andrew Garfield in We Live in Time (John Crowley, 2024) with his unproblematic and personality-free presence. Additionally, this film is further evidence that the Demme closeup may be the most imitated yet overused signature in independent film. Thankfully, once the girls do get together, the film quickly takes on its own freewheeling, addictive energy, constantly stopping and starting over a strange — yet mostly entertaining — 128 minutes.

While Benton’s Z is far too passive to be the lead, trans actress Dezi Bing steals the show as Lauren, seemingly improvising her way through the film with the best joke, line reading, reaction or riff. Far more compelling than Z, she desperately needs her own movie. Even as Dreams in Nightmares fails to satisfyingly pay off its central conflict, her presence alone is fully worth the price of admission.

RB

The Heart is a Muscle by Imran Hamdulay (2025)

“They gave us all their shit.”

Flirting with genre elements before transitioning into a middling reverie on generational trauma, this Cape Town drama has an interesting enough premise but often feels like watching just one thing happen after another instead of a genuinely convincing and propulsive narrative.

It concerns father Ryan (Keenan Arrison), who after his son goes missing at a BBQ, reveals unresolved rage and trauma regarding his difficult upbringing. The first half an hour or so is rather compelling, observing as he navigates a lower-class area than his own, coming into contact with unsavoury characters while doing whatever it takes to find his boy.

But once this initial conflict is resolved, The Heart is a Muscle frustratingly spends the rest of its runtime unsatisfyingly unpacking Ryan’s heightened emotional state, including his fears about being a father, his own complicated relationship with his dad and long-buried teenage secrets. While there is fertile ground to tread here about how a traumatic event can re-open old wounds, this isn’t supported by the narrative itself, which has two or three decent ideas but can’t find a way to make them gel coherently. Awkward and inessential with a sloppy structure.

RB

Monk in Pieces by Billy Shebar (2025)

I can’t say I particularly like the music of Meredith Monk. An unclassifiable blend of repetitive vocal noises, sounding like a cross between yodelling and good old-fashioned New York minimalism, it’s not exactly the thing that either helps me concentrate, relax or simply enjoy myself. But that doesn’t mean that I don’t appreciate the music of Meredith Monk, elegantly and simply explored in Shebar’s documentary.

A key moment comes about halfway through, with Björk’s cover of “Gotham Lullaby” (1981). Suddenly, it becomes obvious that the avant-garde is not just there to impress or shock or be different for the sake of it. It’s essential for pushing the boundaries of artistic expression. Meredith Monk not be to my taste — or yours — but what about the Cocteau Twins, Björk or Sigur Rós? The approach might be standard hagiography — quite literal talking heads1David Byrne! + archive footage — but the overall effect is a strong reminder why the very weirdest artists among us, even those we might not want to listen to at all, are certainly worth cherishing.

RB

Under the Flags, The Sun by Juanjo Pereira (2025)

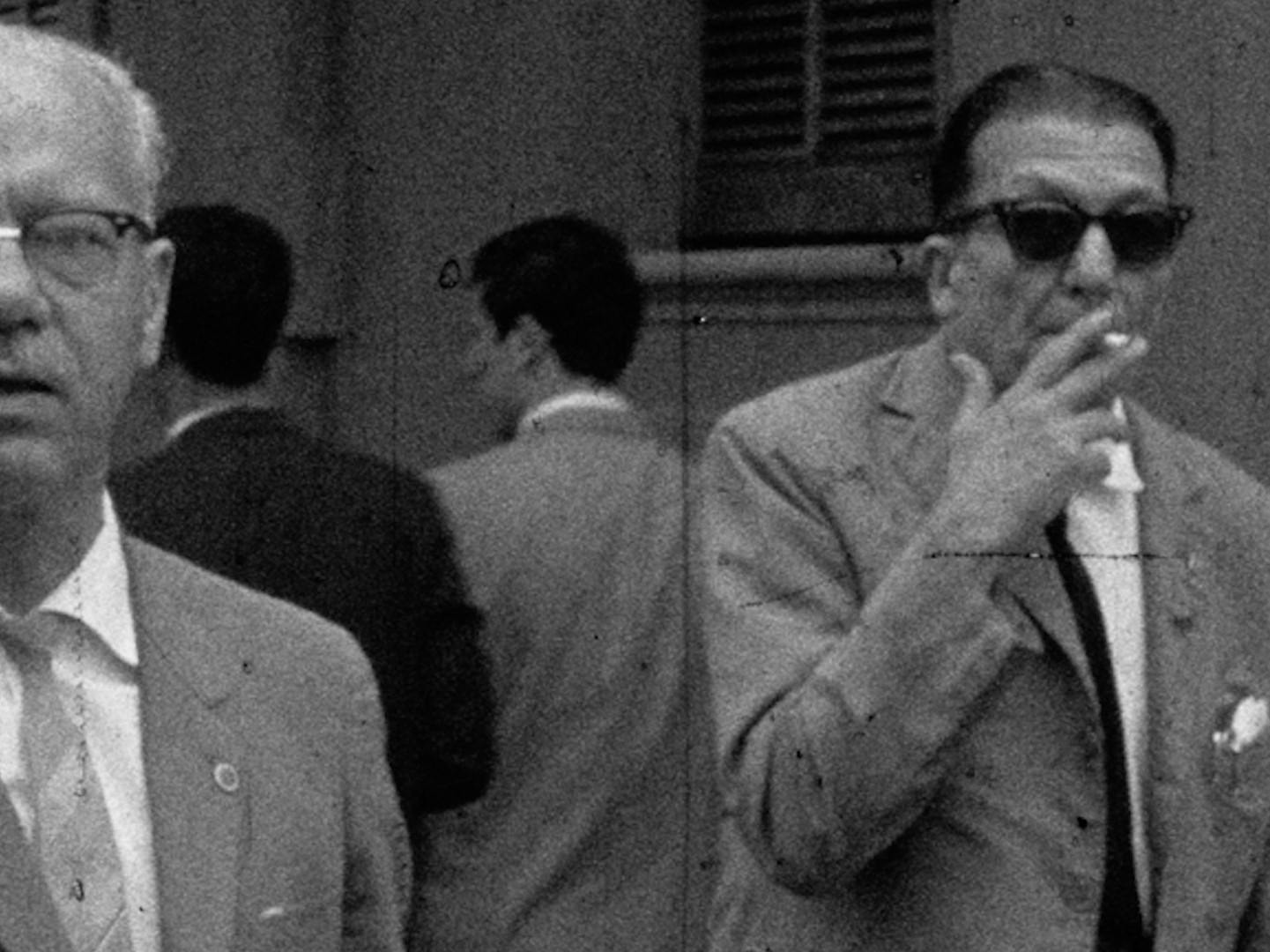

In Under the Flags, the Sun, Paraguayan history is not retold — it is excavated. Built from fragments of rare, lost and scattered archives retrieved from all over the world, the documentary reconstructs the shadow of Alfredo Stroessner’s 35-year dictatorship, one of the longest in Latin America. The film opens with a series of maps, tracing the contours of Paraguay as it has been charted, framed and often overlooked. Before history is written, Pereira suggests, a geography must first exist, positioning Paraguay on the geopolitical stage before plunging into its contested past.

Through crumbling newsreels, silent film-style intertitles, public television broadcasts, propaganda films and official dispatches, Pereira unspools a nation’s past where progress and repression walk hand in hand. The film’s power lies in its contradictions. We imagine visions of peace, prosperity, and industrial ambition — train tracks stretching forward, the colossal Itaipú Dam promising boundless energy — while the soundtrack swells with patriotic anthems. Yet, in the margins, in the missing frames and vanished testimonies, another hidden, erased history emerges, as cinema exposes what was meant to be forgotten.

Political prisoners, exiles, and clandestine reports reveal a Paraguay silenced by fear, while moving images of parades, grand speeches and choreographed displays of unity reveal a narrative manipulated to serve an ideology, craft a national identity in service of power and reinforce the cult of Stroessner, frame by frame. Pereira manipulates the archival footage itself, reversing time and warping images, manufacturing the unsettling, real sensation of a country moving backwards.

When Stroessner falls in 1989, joy floods the streets. His statue is torn down, only his feet remaining, rooted in place. However, as the final card grimly attests, the film does not offer closure, only the uneasy reminder that history, even when buried, does not disappear.

By Massimo Iannetti