It begins and ends with an image of the sky, slightly darkened, clouds whizzing by. We all share this same sky. It’s the world back down on earth that’s so riven by arbitrary and hateful divisions.

Nationhood is an accident of birth. For Russian children, it’s a gross misfortune. Through no fault of their own, they have only known one leader their entire lives. A leader who ferments hatred against foreigners and portrays the once-great nation as a victim of Western aggression. A leader who has made the lives of his citizens considerably worse in favour of enriching himself.

goEast competition entry Manifesto (2022) is a found-footage film, anonymous collective Angie Vinchito collating thousands of YouTube, CCTV footage and TikTok videos to portray the everyday life of Russian schoolchildren. Not since School (Valeria Gai Germanika, 2010) has the future of the nation’s youth looked so bleak.

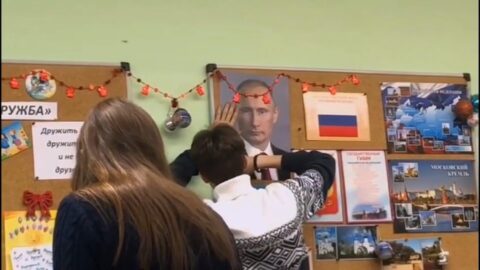

It starts cheerfully. Children doing day-in-the-life vlogs, depicting themselves waking up, stealing a few more minutes of sleep, brushing their teeth thoroughly. But quickly enough, things take a much darker turn. There are air raid tests and school shooting simulations. Physically, mentally and even sexually abusive teachers. The lesson that a woman must always be available to her husband. Image after image after image of meanness, brutality and full-throttled fascism.

In both form and content, it instantly reminded me of Andrey Gryazev’s The Foundation Pit (2020), which also used YouTube videos as a means to collate people’s frustration with Russian corruption and Vladimir Putin himself. The sheer invective in that film — containing a thousand different creative ways of insulting the president — suggested that collective outrage might one day be on the horizon.

Manifesto feels far more pessimistic. To an almost punishing degree. The children are traumatised. But thanks to the power of smartphones and the internet, they are not entirely powerless. They can still bear witness. They can still resist. Standing together, they might just change the future.

Montage, popularised in the Soviet Union by Sergei Eisenstein, is inherently propaganda. It’s a question of what images you chose, how you choose to juxtapose them and most crucially, what you choose to take out. With their deliberate choice of images — including moments that genuinely require some kind of trigger warning — Angie Vinchito have purposefully made a work of agitprop cinema.

But Russia is not a simple, amorphous blob; instead, it is riven with contradictions and varying internal privileges. Life in Chechnya is vastly different to life in Moscow or Irkutsk. The film, featuring various ethnically diverse children, threatens to flatten all their experiences under one. Additionally, you could just as easily find 70 minutes of well-adjusted schoolchildren learning maths as you can dark and disturbing content.

And there is a key ethical issue, compounded by the list of credits at the end. Anyone working in the government can view this film, source the original YouTube videos and find the children who stand up against the government. There is scant information as to whether or not Vinchito — themselves hiding behind anonymity — cleared the use of every clip, but their inclusion is worrisome and potentially dangerous. Welcome to Chechnya for example, managed to use digital technology to protect the visages of his subjects; there’s no reason why Manifesto couldn’t have done the same. This consideration casts a darker cloud over an otherwise important, startling film.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.