35mm, Arsenal Kino

How do you imagine the end of an era? When stasis, moral rot, corruption and a dearth of ideals have set in, calcified — blanketed a people in an impossible state of sadness. How do you point forward to a new nation, a new way of thinking, a new reality?

In the world of Kira Muratova’s glasnost masterpiece The Asthenic Syndrome (1989) — made in Odessa during the death throes of the Soviet Union and playing as part of a retrospective at Arsenal Kino, Berlin — such a concept is impossible. The exhaustion is too palpable. All you can do is sleep. Only sleep, the cousin of death, allows you to momentarily escape your all-too-permeable, miserable, meaningless existence.

On paper, it sounds absolutely soul-destroying. On 35mm film, courtesy of the Dovzhenko Centre, it thrums and crackles with life, wit and a true sense of awe. I’m usually skeptical of hyperbolic statements, but only hyperbole can suffice in the case of describing Muratova’s titanic, era-defining achievement: this is one of the greatest films ever made.

What Are We Even Watching?

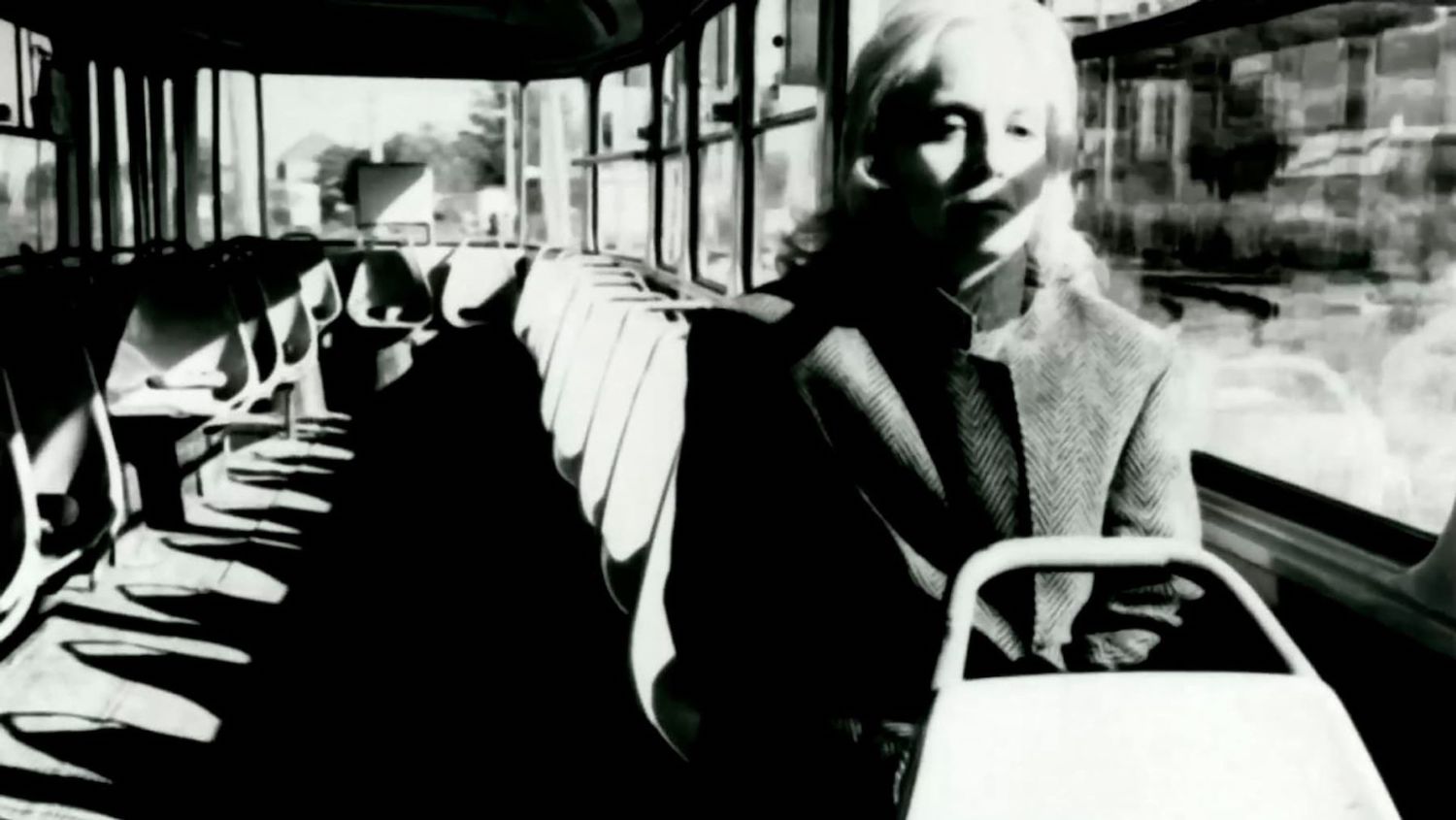

The contrasts in the opening blank-and-white sequence are heavy, the texture of the film — whites blinding out exteriors and blacks swallowing characters whole — evoking the silent expressionist era (digital filmmaking and projection could never!). Natasha (Olga Antonova) is in a dark, nihilistic place. Her husband, somewhat resembling Stalin himself, is dead. While the hero of Brief Encounters (1967) was too sad to do the dishes, Natasha actively hates her crockery. She chucks her wine glasses onto the floor, the sound reverberating around the cinema like we’re in a church.

Antonova totally pushes the boundaries with her unpleasant gestures and actions, actively fighting strangers in the street and writhing around like Isabelle Adjani in Possession (Andrzej Żuławski, 1981). Audiences in the kino awkwardly laughed during these moments. I initially thought the laughter was an inappropriate reaction to this open-hearted expression of grief. Later on, as Asthenic Syndrome piles endless black-comedy motifs on top of each other, I wasn’t too sure. Maybe it is funny?

In fact, with The Asthenic Syndrome — a difficult, complex and basically plotless film — you can’t be sure of anything. Because Natasha’s depression is not even the film. It’s a film within the film. Like with Hong Sangsoo’s A Tale of Cinema (2005), there’s an enormous pleasure to be found in this structural gambit — pulling back the curtain on seriousness and seeing a Soviet audience complaining about the short, including a young child clamouring for ice cream and an older gentleman wishing he saw a comedy instead.

Despite comparisons by the beleaguered moderator to the films of Alexei German, a director whose name I couldn’t quite catch but might’ve been Alexander Sokurov or Mark Zakharov, and Muratova herself (quite right!), no one in the audience (not even the Soviet troops exiting row by row) is staying — no one except for Nikolai (Sergei Popov). He’s completely asleep. Natasha just lost her husband (metaphor for Soviet Union) and he’s asleep. In fact, he’s just gonna go ahead and sleep through the end of history itself.

He’s exhausted. Modern life doesn’t suit him. Hollowed out, confused, a shell of a man, he sleeps. He even sleeps on the metro. At one point everyone is asleep on the metro, pushed against each other, but he also falls asleep getting off the train, blocking everyone in his path. At first, it seems that people are concerned for his health. But instead of dragging him to a hospital, they just prop him against a wall, out of everyone’s way.

He’s a teacher. He tries to tell students about how the bourgeoisie in the West lacks a sense of brotherhood, but he speaks without an ounce of conviction. He asks a student why he isn’t paying attention. He replies he’s looking for the bourgeoisie itself — a fading chimera constructed by the failing state. Pissed, inattentive, uninterested, Nikolai starts a fight. He may be the worst teacher I’ve ever seen.

Sleep Through the Sadness

Sleep allows for an alternate stance on reality. But going to sleep doesn’t mean entering a dream world. It doesn’t mean fantasy. It doesn’t allow for actual alternatives. Muratova might perceive Ukrainian life in the late 80s to be a nightmare, but it’s also real life. A very painful reality. In a series of free-flowing, chaotic vignettes, Muratova takes stock of a world cracking up.

It’s hard to get the tone of films like this right. Self-indulgent, narcissistic, dreamlike cinema — spanning classics like 8 1/2 (Federico Fellini, 1963) and Brazil (Terry Gilliam, 1985) to recent films like Siberia (Abel Ferrara, 2019), Bardo (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2022) and Music (Angela Schanelec, 2023) — works best when some inescapable, internal logic persists throughout. Here, Muratova is in full, terrifying, command of the cinematic form. Everything makes sense, even when nothing does.

Comedy, tragedy, bathos, pathos; all these emotions are mixed and chopped up in Muratova’s solyanka cinema — gathering montage, sex comedy, crowd scenes, adults endlessly talking over each other, kids goofing off, direct address, fish disembowelment, cat abuse and more. Keeping the camera mostly still, while occasionally pushing in for effect, everything is put on the same plane. Here is Odessa on the edge of cracking up. You can either take it or leave it.

I’m glad I watched this in April, T.S. Eliot’s month. Like “The Wasteland”, you are pummelled with image after image after image, heavy with reference and history and implication. They slipped through my hands as I watched them; it’s simply impossible to keep up.

Despite this tsunami of cinematic marvels, Muratova has an uncanny knack for when to speed up or slow down. There’s a moment when Nikolai looks into the mirror for a good few minutes, taking stock of himself, that allows us, and him, to catch our breath, and to simply live with his internal struggle. And humorous juxtapositions — for example, between naked youths lounging to old ladies knitting, or the stuffy stillness of a mental institute with the chaos outside — give the film a true sense of unpredictability. And the weighty two-and-a-half-hour runtime, it kind of breezes by. I’d be happy to have watched for another hour and a half.

History Never Ends

The only movie to be banned during the perestroika, it is truly unlike any Soviet film I’ve ever seen. There’s the copious, full-frontal male nudity, captured in a procession of awkward poses. There’s “Mr. Jones” by Talking Heads (considering who Mr Jones refers to in Ukrainian history, I can’t help but start going full Reddit board on the inclusion) and Silicon Dream’s “Andromeda.” There’s the Spike Lee-esque profanity-laden monologue by a woman in the metro — the “fucks” on the subtitles only capture a slither of comments about your mother’s you-know-what. And there’s the documentary-like footage of dogs in cages, endlessly whining as they jostle for space.

But all of this pales in comparison to one of the strangest, most beguiling, most satisfying scenes in cinematic history. The director of studies at the school plays along to “Strangers in the Night” on her trumpet. It’s superfluous. It’s glorious. It’s cinema for cinema’s sake.

The closest analogue among Muratova’s contemporaries might be Mark Zakharov’s zany, made-for-TV parables, like An Ordinary Miracle (1979) or Formula of Love (1984), which are bound by their own internal logic, even if their strangeness and plethora of Russian in-jokes and references make them impossible for me to actually enjoy. But there’s a seriousness and sadness here that feels monumental.

(It must’ve been an inspiration for Kantemir Balagov’s allegorical Beanpole (2019), where its titular character freezes at random times, often to tragic effect. Now Balagov has retired via social media. Like Nikolai, he seemingly cannot see the end of history once again.)

The film occupied a strange place in Ukrainian reconstruction. There is no hopeful cry for new beginnings, like Viktor Tsoi singing “Peremen!” (Changes) at the end of Assa (Sergei Solovyov, 1987). It proposes nothing. Yet, it’s entirely of its time and could’ve only been made at that time, much as the way Underground (Emir Kusturica (now a fascist), 1995) could’ve only been made in the middle of the Balkan catastrophe. Yet, despite the hyper-specificity, its message, and relevance, reverberates throughout history.

Jonathan Rosenbaum — a massive inspiration to me as a critic because no man loves a digression more than him — despite repeatedly calling Muratova “Russian” (imperialism never ends), got it:

“Even though I’ve never been to Russia, my instincts tell me that throughout the cold war, for all the differences in the ways they lived, Russians and Americans were linked by their common subservience to the same “system” — a system that was neither communism nor capitalism but the cold war itself. And now that the cold war is over, we still seem to be sharing portions of the same destiny and life experiences, thanks to the confusions of the postcommunist aftershock and the whims of the global economy.”

Nikolai may sleep through the End of History, through the imminent fall of the Berlin Wall, through the collapse of the Soviet Union, the reconstruction of Ukraine and its ascensions to modernity, but it’s worth considering that history never actually ended. It got worse. With a madman at the helm in Moscow, Ukraine is once again under the thumb of an insane Russian government, bringing back the Soviet Union in its shitty, Dall-E form. It’s tempting to go back to sleep. To sleep for a very, very long time.

But sleep only provides momentary escape. For some things, you have to keep your eyes wide open. Sleep is no answer to monumental atrocity. But neither, Muratova argues, is art.

Read part one of our Kira Muratova retrospective coverage.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.