When Tricia Tuttle, taking the reins last year, shrugging off the mixed-bag Carlo Chatrian era, announced that the much-beloved Encounters section (I’m much-beloved) was to be removed and replaced with Perspectives — focussing only on debut features — I was pretty annoyed. It’s understandable to want to create a new section and to remove another one to make space. But perhaps, with Forum and Panorama essential parts of the Berlinale experience, the obvious target was Generation. Focussing entirely on films targeted towards children and teenagers, this section never manages to stand out that much on its own.

Why couldn’t the best of Generation simply be subsumed into a different category or both Generation and Encounters considerably slimmed down? Alas, the answer to that question lies within the Kafkaesque halls of the festival itself; probably not worth thinking about too much. Let’s just take a look at the movies we have seen. Perhaps I’m willing to change my mind.

Space Cadet by Kid Koala (2025)

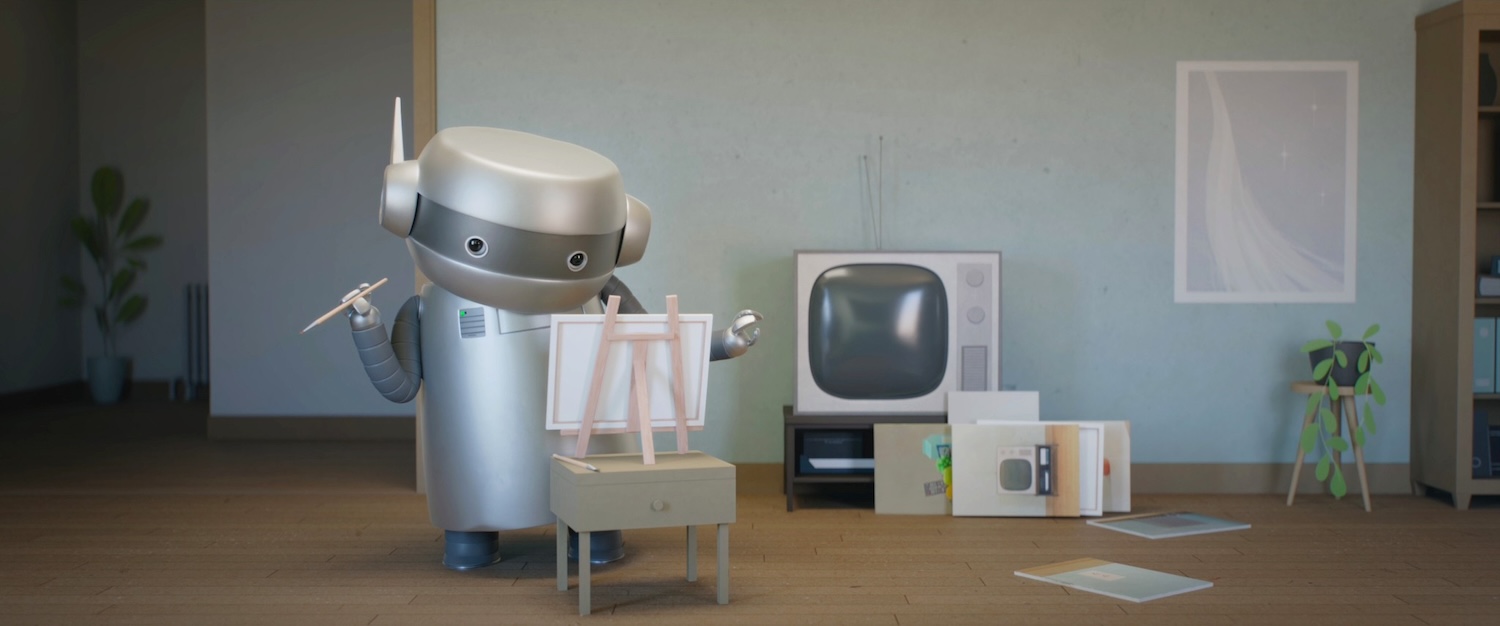

Canadian DJ Kid Koala adapts his own graphic novel Space Cadet in this charming little adventure through the stars, splitting the difference between a robot movie and a sci-fi yarn. The finished product is a little bit like Robot Dreams (Pablo Berger, 2023) — especially as the entire film has no dialogue — meets Lightyear (Angus MacLane, 2022); sharing the first film’s humour and silliness and the latter’s hard-to-shake feeling of intense slightness.

Additionally, the entire endeavour is a reminder that being dialogue-free doesn’t have to mean blasting non-stop music, with many of the jazzy needle drops here awkwardly reminiscent of Hallmark Christmas films. Still, I’m not exactly the intended age group. Young kids are gonna love it when the robot wears a tiny chef hat. (OK, I loved it when the robot wore a tiny chef hat.)

By Redmond Bacon

Sunshine by Antoinette Jadaone (2024)

Switching between goofy magic realism, teenage coming-of-age clichés and a gritty look at the reality of trying to get an abortion in the Philippines — which is prohibited in the constitution itself — Sunshine is a heartfelt story with an angry edge. Maris Racal stars as the wonderfully-named Sunshine Francisco, an aspiring gymnast whose potential tryouts at the Olympics are derailed by an unexpected pregnancy. With no officials to turn to, she is forced to search the black market, where she is followed by a strange young girl (Annika Co) who appears to be a figment of her imagination (it’s obvious when no one else interacts!). While the film certainly draws awareness to this issue of women’s rights in the Philippines, Jadaone’s cornier tendencies overwhelm the message.

RB

Only on Earth by Robin Petré (2025)

Under the scorching sun, the Galician mountains appear frozen in an eerie stasis. Ashen earth and towering wind turbines cast long shadows over a land that has known fire for centuries. Yet, in Only on Earth (feature), stillness is not serenity, but rather a looming forewarning. In the hottest summer on record, wildfires slither through the valleys, leaping forward at speeds beyond human comprehension. As flames, roaring, advance, a cowboy-in-the-making, a veterinarian, a shepherdess and a firefighter struggle to carry on, their daily lives suddenly indistinguishable from an apocalyptic vision of a future already present.

Like a requiem for a vanishing world that has always been there, Petré’s documentary captures both the brutal immediacy of catastrophe and the ghostly silence it leaves behind. Static shots of blackened earth follow galloping horses whose instinct for survival far surpasses that of their human counterparts. Wide landscapes coated in smoke transform the pastoral into the spectral, evoking a sense of accumulated destruction, both environmental and human-made, as if ‘nature’ itself is suffocating under the weight of its own history. The wind turbines, meant to harness nature’s power, stand motionless against the thick sky, a silent testament to human ingenuity and its unintended, naive consequences. Yet, amidst the devastation, a quiet resilience lingers.

Petré’s meditative yet deeply immersive style refuses didacticism, offering instead an elegy to those left tending to the ruins — both of a natural world undone by human hands and of a way of life fast disappearing in the fire’s wake, despite being rooted in it. And then, the rain arrives, like the first hesitant sign of renewal, and for a fleeting moment, the land exhales. In this delicate cycle of destruction and rebirth, hope is not extinguished — it tentatively waits for a moment to return.

By Massimo Iannetti

Maya, Give Me a Title (Michel Gondry, 2024)

The sad thing about love letters (even the good ones) is that they are, by their nature, fuelled by absence. Take Maya, Give Me a Title, in which a father (Michel Gondry, noughties’ indie scene darling) uses animation to reach across the continental divide that separates him from his daughter Maya.

Over the course of six years, young Maya provides her dad with wonderfully extemporaneous titles, which he then uses as prompts to create family films; wacky adventures in which the titular Maya plays the hero of an animated cut-out world. While the prompts come from her, the world is unmistakeably born out of Gondry’s imagination: DIY vibes, tongue-in-cheek humour, the occasional meta reference. These are, literally, films de papa.

And yes, it’s all fun and games, but using cinema to fill in the void of an absence can be a dangerous game (Chantal Akerman’s No Home Movie [2015] comes to mind). Don’t get me wrong, there’s much here to marvel at and smile with: the visual inventions are arresting, the wit is both candid and cutting, and I now desperately want somebody to open a chippy called “Pampa La Frita” up here in Leith. But a whiff of something ever so slightly jarring filters through the cracks. Gondry’s dreamlike logic has a dark twist, with recurring imagery of bodily fragmentation, abandonment, catastrophe. Perhaps it’s just me, perhaps it’s the long shadow of the pandemic, but I can’t escape the impression that there are monsters lurking underneath the surface — fear, or simply the loneliness of growing apart.

By PM Cicchetti