Every artist is a product — and a reflection — of their era.

Nam June Paik grew up in Japanese-occupied Korea, before finding his unique voice — mischievous, playful, chaotic — in 1950s Germany, a land awash in political parallels and the avant-garde. It’s curious how his crucial first influences didn’t come from the visual arts, but the musical world. Harbouring dreams of becoming a composer, inspired by the devil-like, revolutionary music of Arnold Schönberg — a genius or unlistenable, depending on who you ask — his world was forever transformed by a guest concert of John Cage.

While everyone else in the audience either booed or left his chance-controlled work, standing at the nexus between performance art and musical anarchy, Paik was enraptured; striking up a life-long friendship with the composer. This didn’t stop him from getting up in the middle of a performance at Mary Bauermeister’s apartment to cut off John Cage’s tie and shampoo his hair, showing his irreverence for all exalted figures, sympatico or otherwise.

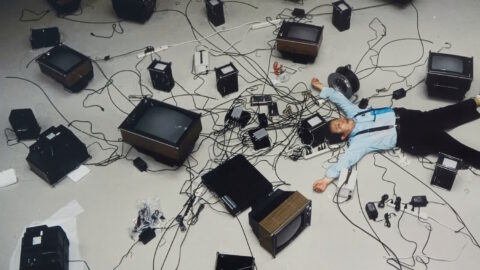

But what really sets Paik apart, as he moves from Germany to New York, and gets involved in the Happening scene, thrillingly explored in Nam June Paik: Moon is the Oldest TV (Amanda Kim, 2023), is not just how he reflected post-war changes in the arts, but how he shaped them; his experiments with televisions and video cameras years — even decades — ahead of popular trends. Fiddling around with the transmissions and feeds of these relatively new inventions, he found all types of unique and provocative images herein, eventually becoming known as the “Godfather of Video Art.”

A variety of talking heads, ranging from artists in their own right (Ulysses Jenkins, Marina Abramovic) to important curators and historians, move this relatively conventional biographical documentary along, which takes us on a neat line from Paik’s tumultuous upbringing to his final work.

It’s mostly worth watching for the extraordinary images alone, from archive footage of bold performance pieces — featuring robots, naked cellists, brassieres made of tiny televisions — to more abstract video work — mad splashes of manipulated light, colour and transmissions — to the era-defining New Year’s Day, 1984 broadcast of Good Morning, Mr. Orwell, which reached over 25 million people across the world. The sheer wealth of material deeply immerses us in his thinking and childlike spirit, paying intense tribute to a man who legitimised video as an art form and broke racial barriers as a trail-blazing Asian artist to make it in New York.

I loved the way he put magnets on television, or visited a network studio for a groundbreaking piece, or how his aesthetic was copied by Prince for the music video of “When Doves Cry” (1984). What I would’ve loved was more nuts-and-bolts explainers on how all the stuff actually works. Moon Is the Oldest TV succeeds as inspiration, but you’ll have to go to art school for a proper instruction manual.

Nam June Paik: Moon Is the Oldest TV plays at DOKUARTS in Berlin, running 4-15 October.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.