The key to a cheap and easy neo-noir aesthetic is simple. Shoot on film and flood the frame with as much fog as possible. Suddenly a street scene has an aura, a menace, a sense of potentiality.

In No Mercy (Richard Pearce, 1986) — made during Richard Gere’s relatively fallow period between An Officer and a Gentleman (Taylor Hackford, 1982) and his 1990 two-punch of Internal Affairs (Mike Figgis) and Pretty Woman (Garry Marshall) — the mean streets of Chicago are drenched in smoke, rising from grates, descending from the air, materialising seemingly out of nowhere. I got the impression that when Pearce was asked how many fog machines he wanted, he simply replied: “Yes.”

It reflects the uncertain world that no-nonsense cop Eddie Jillette (Gere) must navigate during his risky stakeout of a nefarious murder-for-hire plot. It also looks cool as hell.

Sadly, nowadays, as digital cinema is firmly the norm, which somehow looks both murkier and far too defined, fog machines can’t create the same beautiful layer between film grain and the so-called reality of actors working in front of a camera.

No Mercy, seemingly presented on Tubi in its original film scan — and with just 4500 viewers and under 400 reviews to its name on Letterboxd — feels incredibly refreshing when most of today’s action thrillers, especially those made straight for streaming, lack any sense of atmosphere at all.

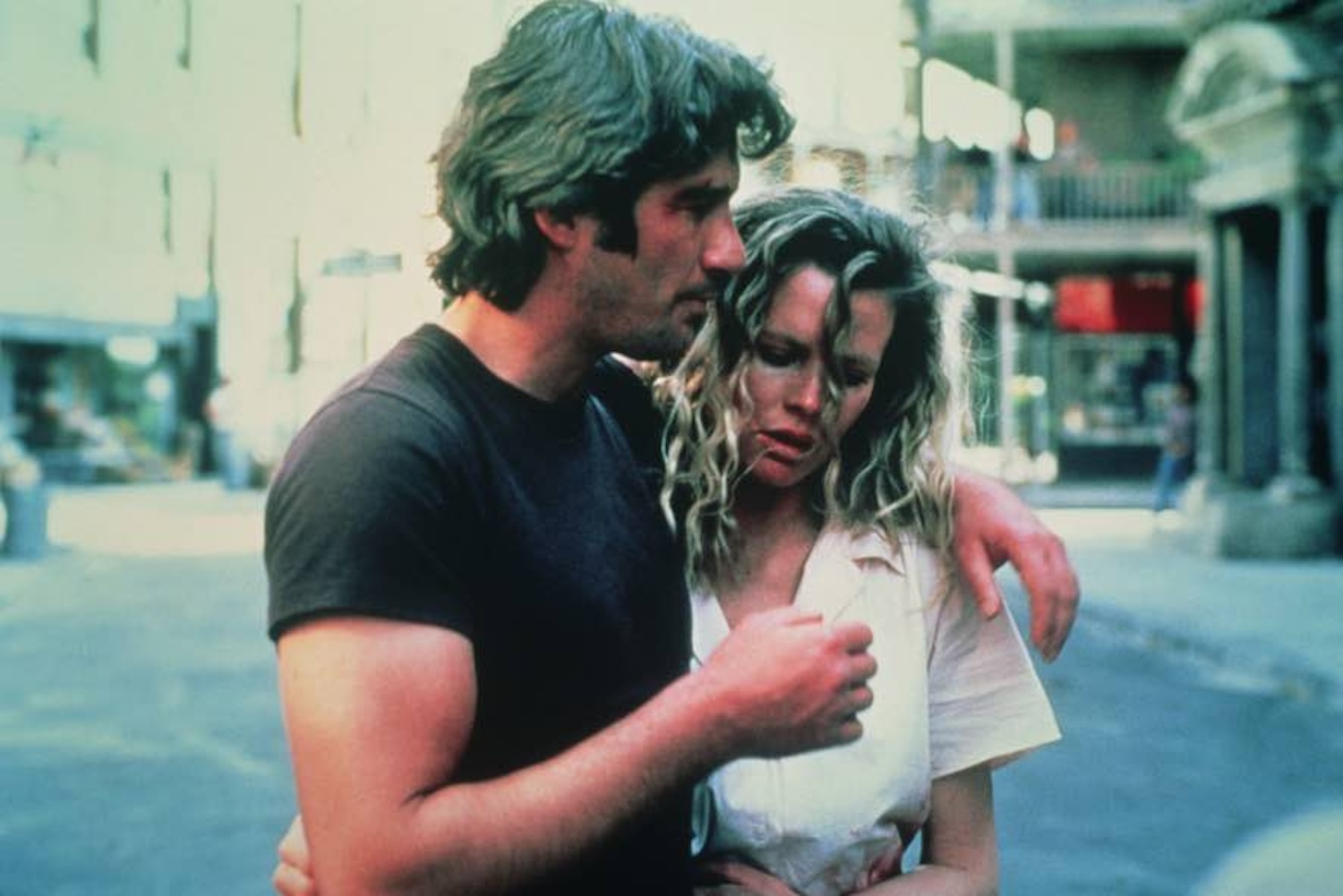

Equally refreshing is how nasty our protagonist is, suffering from a bitter divorce, his love for catching the bad guys equalled by his contempt for the fairer sex. While posing as a contract killer, he insults Kim Basinger’s Michel Duval with misogynist barbs. She slaps him in the face — he hits her back! Most actors would probably lose the audience at that point, but Gere has an intensity and edge that sweeps you along in his misadventures. You might disagree with his methods, but you can’t look away either.

Described by some as a low-budget Walter Hill rip-off, it shares the esteemed director’s use of atmosphere, technical know-how and a penchant for elaborate violence — best represented by an insane RPG kill followed by a chase in a farm along the train tracks. Before we know it, Jilette’s partner is murdered, and he is on the hunt for the killer down in New Orleans. It’s a fish in the wrong water story; Beverly Hills Cop (Martin Brest, 1984) without the jokes.

Mixing between hardboiled barbs — “you look like stale piss” and “She’s got ‘born to screw’ tattooed on her forehead” being my favourites — and a truly wonderful Southern atmosphere, all crocodiles and bayous and an exoticised view of New Orleans as a mixture of white gentry, French cajun hicks and corrupt cops, the vibes in No Mercy keep on rising and rising. It culminates in a truly fantastic club/arrest/getaway sequence, Eddie capturing Michel and tying himself to her with handcuffs before escaping from the bad guys through mysterious and cursed marshland. Cajun culture has rarely felt so mythical.

Capturing this descent into a different underworld, the film purposefully alternates between studio backlots and real locations, imbuing the cop plot with a sense of unreality and far-farfetched developments with a hard edge. The camerawork is rarely showy for the sake of it, yet there’s a really lovely combination of character, plot development and movement here, easily sweeping us up in an increasingly ludicrous story.

Even as the plot leans too heavily on Gere’s star power to get us through a human trafficking plot masterminded by the vaguely European Losado (Dutch actor Jeroen Krabbé in deeply greasy hair mode), No Mercy’s first two-thirds feel completely immaculate. But sadly, in many films like this, especially in the 80s, two things must happen: the leads must have sex and the good guy has to shoot the bad guy in a generic gunfight.

With so much sexual tension throughout the movie, best represented in a clothed shower scene with both Gere and Basinger still tied to one another by handcuffs, it’s a shame that the consummation scene feels so generic1(This is especially true when you consider that 9 1/2 Weeks (Adrian Lyne, 1986), also starring a sultry Kim Basinger, was released the same year and that Gere and Basinger may have been having an affair, at least according to her-then husband Ron Snyder-Britton’s memoir.). Yet this is nothing compared to the final shootout, trading in all the film’s neo-noir chips in favour of a true ending-by-committee2Similar things happen in Ridley Scott’s Black Rain (1989) — one of Hollywood’s most beautiful movies sadly undone by a by-the-numbers finale..

Still, Pearce finds a way to salvage something by the final shot, the characters descending into Bourbon Street, yet more faces in the crowd, their story one of millions swirling about in that crazy ol’ city of New Orleans.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.