Koffi (Marc Zinga) is shaving his huge afro. A symbol of empowerment for Black people in the Western world, it is viewed with suspicion back in his home country of the Democratic Republic of Congo. His white Belgian wife Alice (Lucie Debay) might be sad to see it go, but it’s a choice he has to make in order to fit in.

Omen (Baloji, 2023) follows the young couple as they return to Koffi’s hometown to deliver a dowry, first promising a story of racial prejudice and misunderstanding before burrowing deeper into a mystical, enigmatic exploration of social exclusion, superstition and the difficulties of letting go. Prioritising spectacle and image-making over conventional plotting, and sensitive contemplation over high-handed drama, this promising debut sensitively counts the cost of living outside the norm and the paradoxes inherent in returning home.

It starts to go downhill when Koffi asks for directions. Nobody responds to his attempts at Swahili. But when he speaks French, they know exactly what he means. And his family are standoffish, not because of his white girlfriend, but because they consider him to be the devil. In one of the film’s most gripping and effective scenes, a minor nosebleed is blown out of all proportion, and he is placed under a fascinating, shocking local ritual. At one point, I thought Congolese-Belgian rapper-turned-filmmaker Baloji was going to make a folk horror movie, all lurching camera angles and crazy customs, but instead, this moment is a springboard to welcome us into a different world.

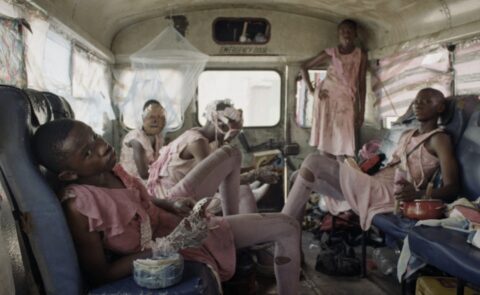

While Omen might be a Belgian production, its Congolese focus foregrounds a central African perspective over any conventional European thinking. When asked if she would like to live in Europe, Koffi’s hip sister Tshala (Eliane Umuhire) quips that Europe’s been over since 2008, especially when there are more exciting destinations nearby like Nigeria and South Africa. Kinshasa itself is marvellous enough, like a wrestling match in the middle of the town with fighters decked in bright, pastel colours, accompanied by a raucous musical parade. The hustle and bustle of the city allows Koffi’s story to then interweave with Tshala’s experiments in polyamory and a young boy defending his sister’s honour, adding both harmony and counterpoint to his struggle.

And in a refreshing development, Alice — the film’s only white character — is not a typical, ignorant European. While she is certainly startled by cultural differences, she looks at it in the context of her relationship with Koffi, rather than offering blanket judgments of Congolese custom. Her real problem is any real lack of psychological interiority, with rarely much to do other than support Koffi’s journey.

Alice is told that unlike in Belgium, children in Congo are not supposed to raise their voices against their parents; to remain meek and do as they say. This feels like a metonym for Omen as a whole, which sets up many fascinating contradictions but can’t find a satisfying way to challenge them. It feels too reverent. Too safe. Too easy. Especially with an ending that feels like the perpetuation of the same stasis. We’re left with brilliant documentation, not enough dramatic invention.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.