When I was last in Paris, my friend, on a banking secondment abroad, took me to La Défense, the striking banking district — all glass and steel — three kilometres west of the city. Standing underneath the Grande Arche, one can look far into the city, a straight shot to the Arc De Triomphe and the Louvre Pyramid.

This is the Axe historique, essentially one huge line that also includes the Palais de Congrès and the Obelisque. We tried to visit most of those monuments on that day, before having a few shop-bought beers under Mitterrand’s Library, perhaps my favourite of his Grands Projets, eight monuments specially built in the 1980s to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the Republic.

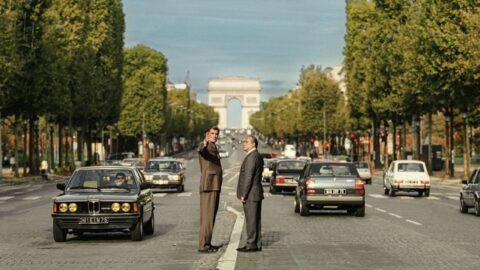

Crowdpleaser The Great Arch (Stéphane Demoustier, 2025) is wise not to create a biopic of all these different projects, but instead hones in on the unlikely story of Grande Arche and its reflection of the unflinching artistry of Danish architect Johan Otto von Spreckelsen (Claes Bang). It starts in the grand halls of power, caught in the geometrically pleasing square format, with the announcement of the winner of the Grande Arche commission, picked by François Mitterrand (Michel Fau) himself. It causes quite a stir amongst French circles, as, by his own admission, von Spreckelsen is a humble artist, having only previously designed a handful of churches back in his native country.

The resultant film is a three-star one-screen arts centre banger, a film that is often interesting and entertaining in its clash of ideals and historical recreations, but — despite many dramatic shots of men dwarfed by construction works — never reaches the monumental heights that such a great building deserves. Most of the conflict is found in von Spreckelsen’s heated conversations with project manager Paul Andreu (Swann Arlaud), who tempers his most ambitious ideas. Here, Arlaud, like in Anatomy of a Fall (Justine Triet, 2023), reveals why he is one of the best supporting actors in the business, able to draw out different layers of Claes Bang’s character that a lesser sparring partner could not. Their relationship — and squabbles — are the true heart of this pleasing, if somewhat underwhelming work.

Betraying their philosophical roots, architectural dramas, from The Fountainhead (King Vidor, 1949) to The Brutalist (Brady Corbet, 2024)1Which this film evokes in a visit to an Italian marble quarry., usually always reflect some kind of Randian fantasy: that of a single genius striving to complete their vision in the face of paper-pushing bureaucrats, a vision that is not only the selfish ideal of artistic perfection, but that which will always benefit wider society as a whole. What complicates this conventionally right-wing fantasy, however, is the fact that Mitterrand was an acclaimed socialist leader, with his ideals for great and lasting monuments in Paris part of uplifting society as a whole. This makes the film a rather comforting throwback, an evocation of a time when leadership was filled with big and bold ideas, and nationalism could mean building and doing amazing things, and not just the nasty voice of xenophobia and austerity.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.