While the first half of my Berlinale Shorts coverage focussed primarily on disembodied and alienating films, the second half goes deep on the emotions, kicking off with a wonderful love story and deep, emotional tales before eventually taking us across former Yugoslavija. Then there are just a couple of shorts that didn’t fit nicely into a thematic box — and I wasn’t particularly impressed with anyway. Let’s look at the rest now!

Love, Sex (and Everything in Between)

Close to September by Lucía G. Romero (2025)

Spanish entry Close To September is the most straightforward of the Berlinale shorts, but also the most effective. It concerns Alejandra (Ana Barja), who lives in a campsite by a holiday resort with her mum and three sisters, yearning for more from her life, living vicariously through the tourists who flit in and out of the area.

With just the short format, Romero gives us a sense of an entire world; cheap beer and discotheques, hotels with kitsch live entertainment, intense yet fleeting friendships, the desire to escape.

Always wearing some kind of sports jersey, Alejandra is a closed-off yet playful person, Barja skilfully portraying the type of woman excellent at seduction but terrified of intimacy. She seems unwilling to fall in love because she knows that every relationship has a baked-in time limit. Romero slowly breaks down her walls however when she meets the beautiful Amara (Isabel Rico), crafting a tender, heartwarming story of what it means when you allow yourself to truly be vulnerable. I really liked this one.

Extracurricular Activity by Dean Wei and Xu Yidan (2024)

Extracurricular Activity’s ice-cold aesthetic, matter-of-fact plot development and no-nonsense characters, forcing us to figure out and participate in the plot instead of having everything spelt out for us, slowly betrays a burning interest in the remarkable strength of motherhood. This Chinese film is highly deliberate and slow, almost documentary-like in its portrayal of a late-night trip to the pharmacy to avert an emergency, yet it burns with great intensity thanks to a highly-focussed performance by Tu Ling as a mother immediately taking the reins in the wake of a disaster. Hypnotically assured.

Because of (U) by Tohé Commaret (2025)

A French film of fleeting impressions and sensations, most notably a feeling of intense loneliness as our protagonist, a girl in her late teens or early 20s, navigates empty and bleak banlieues as well as her narcissistic boyfriend. This is Commaret’s follow-up to the astounding 8 (2023). When reviewing 8, I said that it “illuminates cinema’s true potential as an oneiric medium.” Because of (U) might have a similar locale and theme, but the overall effect is much flatter, its omissions less of a chance to engage the imagination than simply tedious and empty space. A hard one to hold on to.

Living Stones by Jakob Ladányi Jancsó (2025)

The Hungarian Living Stones — exec produced by none other than the maestro, Béla Tarr, himself — is an exercise in provocation, from its startling opening image to the shocking end credits. Yet I don’t think it’s gratuitous and nasty for its own sake. I think it’s using these images as a way to burrow us deep into the psyche of its damaged protagonist, and to see the world the way she views it. An excellent Lilla Kizlinger stars as Natasa, a suicidal young girl working with a therapist in a rehabilitation centre. He constantly asks her uncomfortable questions as the camera leers even more uncomfortably close to her face. Jancsó is particularly accomplished at creating an ever-increasing sense of dread, the final result a disturbing peek into a world off its axis.

Casa Chica by Lau Charles (2025)

The difference in perspective between a five-year-old and an 11-year-old is clearly delineated in this deeply perceptive Mexican film, showing the same events from two points of view. For the young Valentina, her world is all immediate sensation and reaction, but the older Quique is able to see and already understand the painful reality of the adult world. Effortlessly naturalistic with two great child performances, Charles’ film expertly captures the heartache of growing up too fast and too soon.

Former Yugoslavia

Koki, Ciao by Quenton Miller (2025)

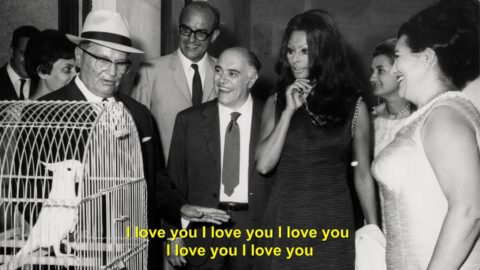

Someone on TikTok once wrote disparagingly of Film Bros for wanting to watch a “2 hour black and white movie about the Serbian government shown through the eyes of a pigeon” instead of the latest Marvel film. The backlash was immediate: who doesn’t want to watch a two-hour black-and-white movie about the Serbian government shown through the eyes of a pigeon? Well, substitute a pigeon and replace it with Koki the cockatoo, and Koki, Ciao (feature image) gets you as close as possible to this mythical dream.

Koki was no average cockatoo but was in fact Josip Broz Tito’s (leader of Yugoslavia, 1944-1980) personal pet! Mixing static frames à La Jetée (Chris Marker, 1962) with footage of the animal himself, well past 60 as he shouts “Tito! Tito!” in his enclosure in the Croatian Brijuni islands, Miller’s film is light on its feet but fascinating in content — especially as the cutie Koki might not be all he seems…

Ceasefire by Jakob Krese (2025)

Nearly 30 years have passed since the Srebrenica genocide in Bosnia, yet many survivors still live in refugee camps across Bosnia, where they are often treated like second-class citizens. Jakob Krese’s film focusses on survivor Hazira, who still lives in what was meant to be temporary accommodation. Constantly toiling to keep the trauma at bay, she is a lively and spritely woman, but one forever scarred by the horrors of war and hatred.

The film thrums with contemporary resonance, not only the war in Ukraine and the ongoing, never-ending situation in Gaza but also the relentless, terrifying Islamaphobia that exists all over Europe, most recently seen in the U.K. hate riots of 2024. Ceasefire shows us the chilling end result of such evil rhetoric.

And The Rest

Lloyd Wong, Unfinished by Lloyd Wong and Lesley Loksi Chan (2025)

A note from a close acquaintance of Canadian artist Lloyd Wong, presented via intertitle around halfway through this artless video discovery, states that “I think it’s interesting you’re taking a structural approach / you don’t have to bring insight.” It’s less a clue to understanding Lloyd Wong — which is composed of his unfinished VHSs from the 90s, created as he was dying of AIDS — than a tacit form of apology. The problem is that this film not only doesn’t bring any insight, it doesn’t take much of a structural approach either.

Anba Dlo by Luiza Calagian and Rosa Caldeira (2025)

Berlinale Shorts tend to prioritise atmosphere over plot, which is certainly the case with Anba Dlo, which is less about what you see and more about what you hear. The buzzing of cicadas. The crackling of a fire. Mysterious voices in the air. Telling the story of a Haitian migrant working as a researcher in the Cuban jungle who longs for home, Anba Dlo certainly creates an inviting and solemn aesthetic, yet failed to invoke in me any genuine sense of catharsis.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.