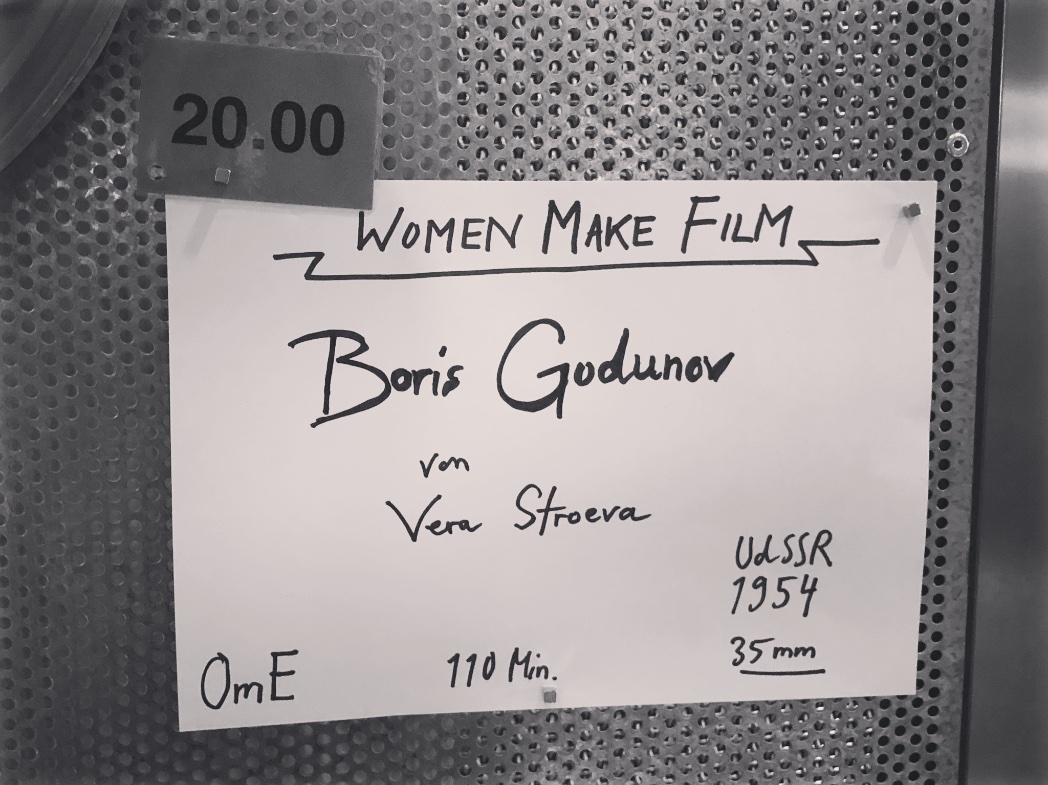

Arsenal Kino, 35mm

Potsdamer Platz was once a no-man’s land; a strip of barren nothingness between East and West Berlin. In many ways, it is still a no-man’s land, a place where anything can seem to spring up in the midst of vacant, absent-minded capitalism. The Arkadan, returning after the curse of COVID-19 and endless renovations, is finally back. Now it’s called The Playce.

There’s some contemporary art around the mostly barren building, but its efforts at rejuvenating the space are a colossal failure. The biggest shop is a massive NBA store, as we all know Germans are obsessed with Magic Johnson. And the second floor is occupied by a huge gaming zone — basketball games (sensing a theme here), racing games, a trip to the world of Kong: Skull Island (Jordan Vogt-Roberts, 2017). The kids are there. Young, sugared-up little ones, and emos, punks, scene kids. It’s like a parody of the classic American mall, an institution that’s dying over there, let alone over here in Berlin.

A decaying future seems rampant around these parts, taking anything that was once soulless and ramping it all up to yet another degree. Luckily there is still an institution across the street that regularly journeys through the past: the Arsenal Kino, a magical place filled with regular restorations, special screenings and retrospectives. A place where the past can be cradled, illuminated and held up to the eye once more, if only for a little while.

A Different World Entirely

The world of Boris Godunov (Vera Stroyeva, 1954) — playing as part of Arsenal’s Women Make Film series, dedicated to thirteen lesser-known women directors (hence the shitty feature image quality) from all around the world — couldn’t be further from either Potsdamer Platz (an anti-world, I would argue) or from most trends of contemporary cinema.

After some text preamble, explaining how Boris Godunov takes the throne in 1598, we are immediately immersed into the universe of Tsarist Russia; brought vividly to life through Soviet Magicolour. The tones and hues are hues are more muted and gloomy than their American counterpart, yet this magic, swirling, almost mysterious colour-scheme has a true weight and solemnity that feels perfect for the tale’s innate piousness and pageantry.

It’s one of many film adaptations of the Boris Godunov story, originally written as a play by Alexander Pushkin and adapted as an opera by Modest Mussorgsky. After Eugene Onegin (also a Pushkin story, adapted by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky), it’s the most famous of Russian operas.

It’s had many cinematic treatments. The great Sergei Bondarchuk (director of War and Peace (1967) and father of hack Fyodor) made a version of the play in 1986. Polish auteur Andrzej Żuławski adapted the opera in 1989. I cannot speak for those versions, yet Stroyeva’s adaptation, captures the spirit of the thing excellently, bringing in classic mid-century Russian opera figures such as Alexander Pirogov, Georgii Nelepp, and Maxim Mikhailov to sing well and move slowly and lament and cry and shout, excellently capturing a nation on the verge of destruction.

To summarise: Boris has risen to the throne, but like Henry IV, his head is heavy with the crown. He is consumed with guilt over ordering the death of the true heir Dimitry. His reign is further complicated by the apparent resurrection of said Dimitry, leading to much hand-wringing, walking doggedly around rooms, endlessly clutching his chest, bewailing his fate and asking God for forgiveness.

Pirogov imbues Boris with deep psychological feeling, the camerawork still fresh in the way it follows his movements, moving from medium, distanced shots, to painful close-ups or POV perspectives. The lighting is constantly changing, the lighting or extinguishing of a candle changing the colour of a scene, shadows in the background rising and falling, slowly surrounding Boris and threatening to envelop him.

Guilt can be easily extinguished, if you are forgetful, but rumours of Dimitry’s resurrection (a conceit that is rather funny once you know the actual ending of the story, and startlingly bemusing when you realise that this may have actually happened) threaten to chase Boris wherever he goes. Right from the second he is crowned, one can guess that this won’t end well.

There are relatively few scenes in this film, which is both episodic and epic, intimate and sweeping; making use of vast panoramas as well as touching indoor scenes. Like Eistenstein’s Ivan The Terrible (1944), the sheer pomp and circumstance, the vast amounts of regalia and the amazingly-detailed interiors seem way too over-the-top to ever be real. (Neither did the Queens funeral, to be honest.) The light sparkles off the rubies on Boris’ breastplate, dazzling both the audience and the poor people around him, their faces, piled in rows and rows and rows (and there’s no copy-paste extras here, unlike The Rings of Power), filled both with devotion and a touch of fearfulness.

It’s history that plays like fantasy, creating a world that seemingly only exists these days if there’s some dragons to go along with it. This is further heightened by the use of beautiful matte paintings, expressive skylines (including a Red Square literally drenched in a gorgeous red sky), and religious imagery, including a spooky procession of Boyars in black hoods, shuffling through mist, foreshadowing Boris’ eventual demise. The ideals of classical painting never seem far away, the compositions carefully combining foreground and background, rarely capturing characters head-on, but showing them in relation to the rest of the players caught in the academy ratio frame, making for a rigorous and satisfying mise-en-scène.

Kyiv-born director Vera Stroyeva creates a great, wondrous film even as Mussorgsky’s music thuds and smashes and endlessly rises and rises, oftentimes blunting the beauty of the images, the expressiveness of the acting and the fantastic singing. At 110 minutes (25 minutes shorter than the official opera, minus the interval), this version of Boris is good enough for me (sorry).

I’m not too tempted to check out the other versions any time soon, but if they turn up on my doorstep, I would like to see how the storyline differs; and what other techniques are used to illuminate these deeply sad tale.

And it’s depressing in its familiarity. An incompetent leader, plagued with guilt, heralding the advent of disaster. It’s over 400 years ago. It’s the same as it ever was. Some things — unlike the constantly metastasising Potsdamer Platz — never change.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.