If you ever want to see the pinnacle of method acting — whereby an actor displays as much emotional and physical identification with the role as possible — then all you have to do is watch any film by John Cassavetes starring his wife and muse Gena Rowlands. When watching her on the big screen, it’s hard to think of anyone else who does it better.

She’s not even considered a classical “method” actor per se. That honour goes more to guys like Marlon Brando and Dustin Hoffman, a consideration rooted more in old-school sexism, with only brave men seen as truly embracing this style, than any real level-headed consideration of acting ability and preparation separate from technique.

Because when you watch Gena Rowlands in films like A Woman Under the Influence (1974) and Love Streams (1984), what you observe is this total sublimation to the role, a woman totally consumed by her character, able to express higher pitches of emotional range than perhaps anyone else in American cinema.

And the most entertaining I’ve seen her was just a couple of days ago here in Karlovy Vary, at the charming Municipal Theatre.1 Particularly of note was the introduction, where the programmer mentioned that they try to programme at least one Cassavetes film a year. In Gloria (1980, above), she plays a tougher-than-nails, self-described “old broad,” on the run from the mob when she’s entrusted with the care of a young boy whose family has been murdered as a warning shot not to betray them. Capturing the swagger of someone who knows that rundown, lived-in New York world while never failing to show us the contradictions and fear of taking on these real bad guys, her performance imbues a genre idea with an uncommon emotional power.

But if Gena Rowlands had trouble breaking out of her husband’s films and into the mainstream — by the way, she is also brilliant in Woody Allen’s underrated Bergmanesque Another Woman (1988) — this is nothing compared to the almost forgotten legacy of John Garfield, who predated Marlon Brando many years prior in his use of the Stanislavki method. With training at the American Laboratory Theatre, opened by Moscow Art Theatre alumni Richard Boleslavski and Maria Ouspenskaya, and “The Group,” which counted Stella Adler and Elia Kazan among its members, his style of acting in Hollywood was perhaps the first example of the Method Acting working on the big screen itself.

I managed to catch just three of his films at the festival: The Postman Always Rings Twice (Tay Garnett, 1946, above), Force of Evil (Abraham Polonsky, 1948, feature) and Body and Soul (Robert Rossen, 1947, below). The first two are noirs (although Force of Evil, less so) and feature Garfield’s embittered voiceover, sweeping us up into his convoluted and nefarious schemes. His particularly endearing quality is his ability to shoot out dialogue like he’s firing from a pistol, as well as his rough-and-ready seductive charm, more sleazy and more New Hollywood than anything you might expect from the Golden Age. And the best line comes in Force of Evil, when, seducing Beatrice Pearson, he says, “Tell me your life story and I’ll give you a happy ending.”

It’s a shame then, that, The Postman Always Rings Twice — despite having one of the coolest names of any film noir title, and Lana Turner’s drawdropping blonde bombshell beauty — doesn’t quite match up with the classic noirs of the era, featuring an extremely convoluted plotline and a weird sense of melodrama that belies its supposedly cool premise; a man coming out of nowhere and trying to take a man’s wife — then his business. Still, it has one brilliant zinger: “Stealing a man’s wife, that’s nothing, but stealing a man’s car, that’s larceny.” Faring better than Garfield, in my view, is Hume Cronyn as cynical lawyer Arthur Keats, who, when defending the murderer and his lover, comes up with an extremely smart, albeit ridiculous, form of defence.

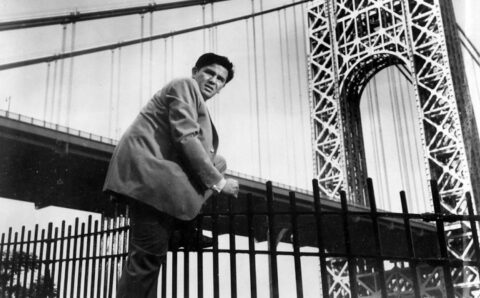

Force of Evil, presented on crackly 35mm film, with a few seconds missing here and there, is far better, even if its plot is also needlessly confusing. It feels like Garfield, playing a lawyer representing an illegal lottery numbers racket, learned a trick or two from Cronyn, delivering his lines at a mile a minute, while pushing his embattled brother Leo (Thomas Gomez) into his nefarious scheme. With scenes shot on location in New York, as well as a truly cynical atmosphere, this 79-minute film displays an actor in full, fascinating command of his craft.

Garfield is simply great. Martin Scorsese says it better than I: “The face of John Garfield… was a landscape of moral conflicts.” Here we see the origins not just of Marlon Brando, but Mean Streets (1973) and the acting styles of Harvey Keitel and Robert De Niro; the mob man with a kind of strange charm, a mostly-bad person you can’t help but root for.

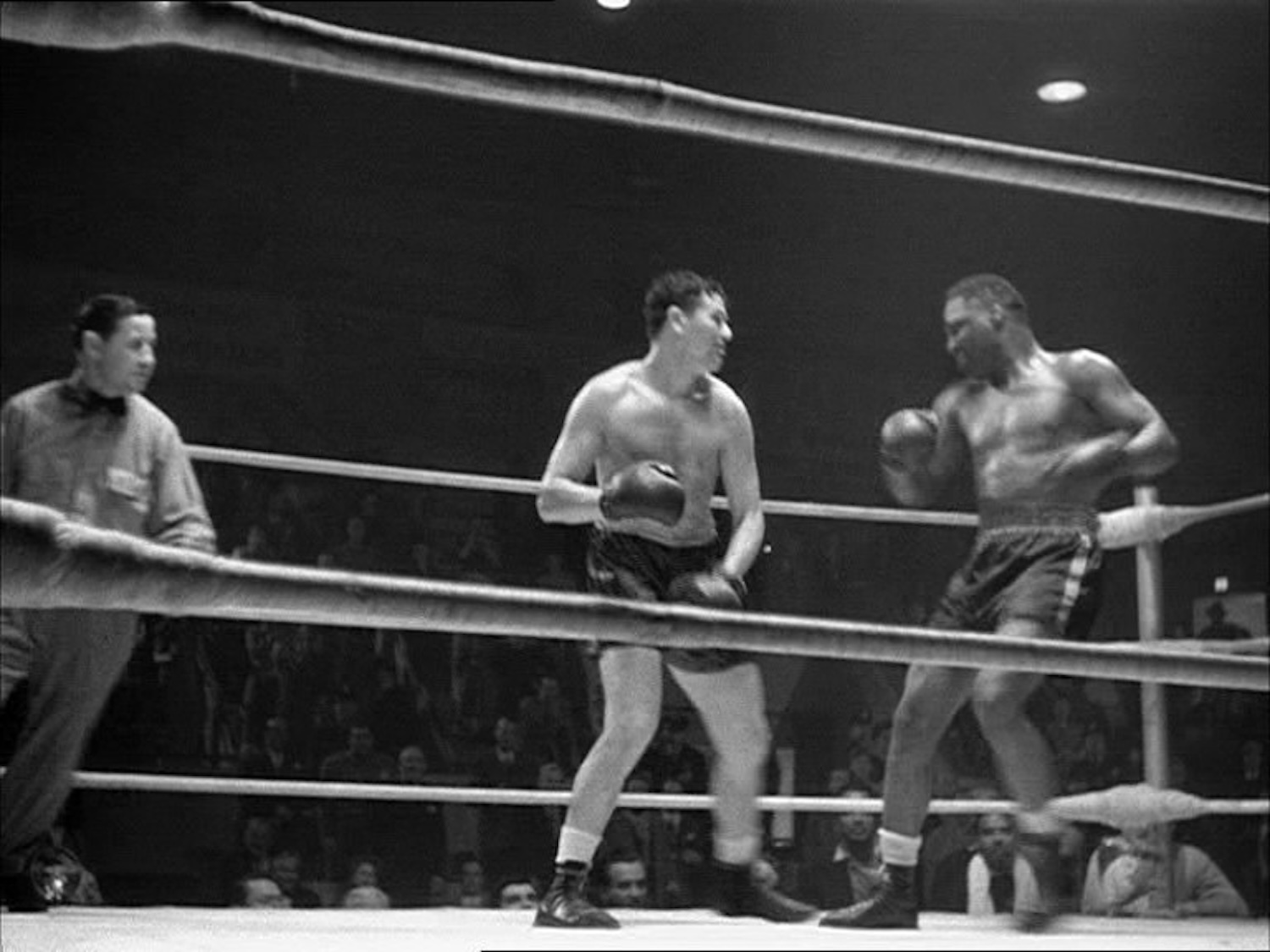

This Scorsese comparison is further stressed by the phenomenal boxing picture Body and Soul (also written by Force of Evil scribe Polonsky), where Garfield plays the aspirational boxer Charley Davis, who is the victim of his own success when he becomes surrounded by a whole gang of nefarious characters who fix games and turn his scrappy, can-do spirit into something far more nakedly capitalist. Shot by the legendary James Wong Howe, the sweaty black-and-white boxing scenes, also presented on a mesmerising local film print, predate Raging Bull (1980) by over thirty years; bobbing and weaving with ultra close-ups, leering movements, a sense of brilliant disorientation. Here, Garfield’s incredible performance — laying the groundwork for Jake LaMotta — somehow eclipses the other two films, alternating between a fiery intensity and a deep sense of self-loathing, warped by a deep greed and a sense of perpetually wounded pride. This one is really special and makes me want to binge as many classic boxer pictures as I can.

These days, method acting is disparaged as an excessive, often-silly thing — see House of Gucci (Ridley Scott, 2021). Yet, the work of Garfield and Rowlands reminds us of how useful a tool it can be, taking archetypal roles and turning them into something deeply personal and human. And screenings like these reveal their usefulness in redirecting the conversation when it comes to who is worth revering in the larger acting canon.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.