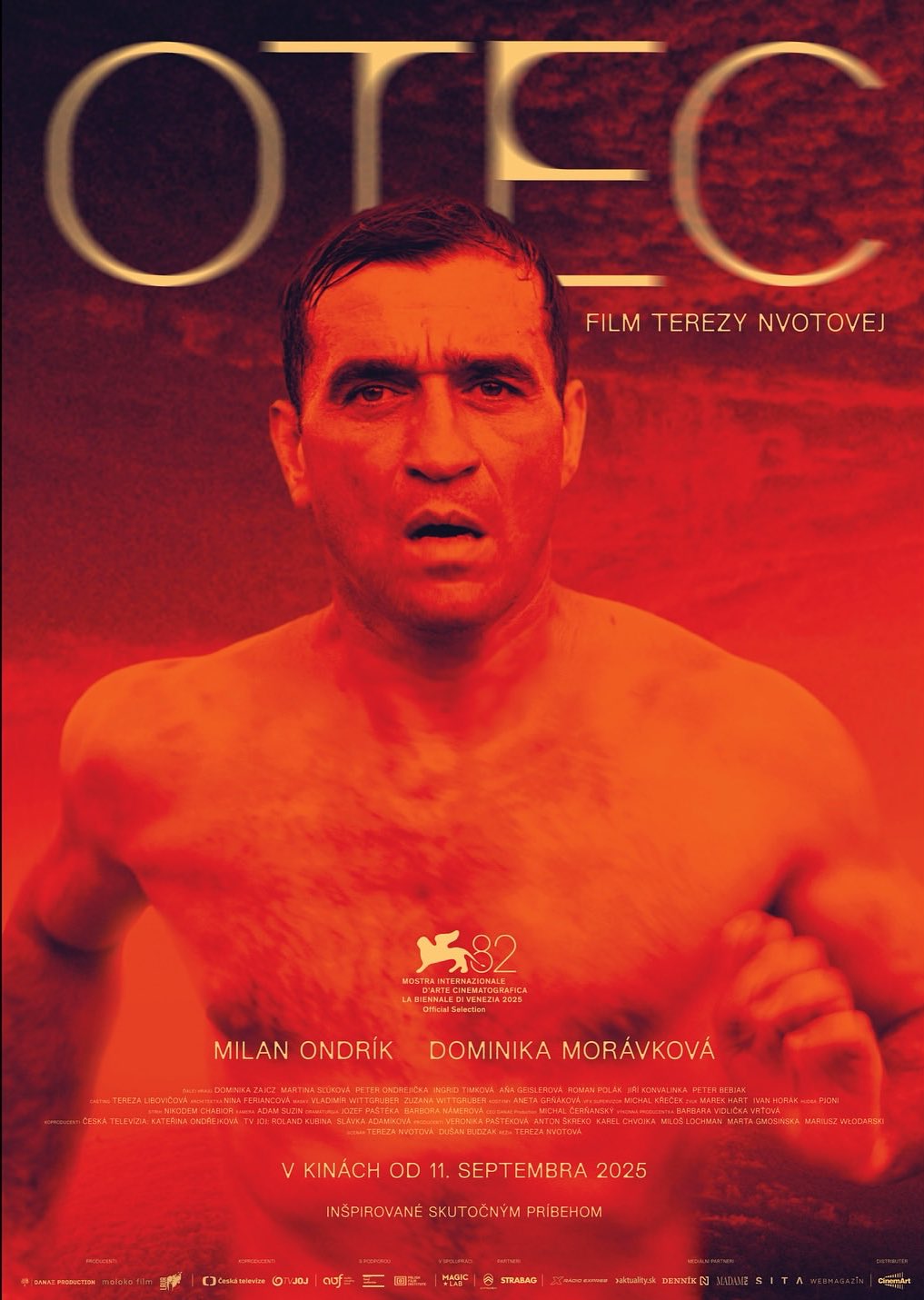

I hate to make light of a film about such a devastating subject, but when I shared one of the posters for Otec (Father, 2025) — Tereza Nvotová’s gripping new drama — in a group chat, one of my friends, knowing the plot, asked: “LOL, why is he naked?”

I replied, “You’ve got to sell it somehow! No one’s going to rush to see this based on the synopsis alone.” Jokes aside, the image on the poster of a man looking like he’s jogging through the depths of hell is a perfect representation of what happens in the film — a relentless plunge into psychological torment.

Based on a true story, the film centres on a father experiencing what’s known as Forgotten Baby Syndrome — a phenomenon in which a parent, due to a lapse in memory, accidentally leaves their child in a hot car. It happens around 40 times a year in the U.S. alone. It’s not a formally recognised medical diagnosis, but there’s a decent amount of neuroscience backing how and why it happens. In short: the brain’s “autopilot” — our habit memory — can override cognitive memory under stress. You think you’ve dropped the baby off because your brain feels like it has already completed that task. But you didn’t.

The story begins like any ordinary day. After a morning jog, Michal (Milan Ondrik) returns home to his wife, Zuzka (Dominka Moráková), and their two-year-old daughter, Dominika (Dominika Zajcz). Both parents are frazzled — a bit stressed about work stuff and running late. Zuzka asks Michal — who doesn’t usually handle daycare drop-offs — to take Dominika that morning. But before he can fully shift into that role, his brain goes into autopilot: he drives straight to work, genuinely believing he’s already dropped her off, unaware she’s still in the backseat. After six hours alone in the hot car, she dies.

Nvotová makes a smart choice by showing us the drop-off as Michal imagines it, showing a mental fabrication that happens in real time. When he realises what’s actually happened, we’re just as disoriented as he is. It’s a chilling demonstration of how convincingly the mind can rewrite reality.

The film follows a clear three-act structure – the setup, the immediate aftermath, and then picking up months later with courtroom proceedings. All three are equally gripping, thanks to both the deliberate choices in cinematic language and the unwavering commitment from the cast. It would be hard to imagine a more emotionally harrowing subject to tackle, and this kind of narrative demands everything from its leads. Much of Ondrík’s performance hinges on sustained emotional intensity — a lot of crying and outbursts and pained expressions — a man haunted by something he regrets but still can’t fully comprehend. It looks so unbearably exhausting to film, and he’s just fantastic.

The post-tragedy scenes, where the parents process their grief in different ways, are quite difficult to watch. Michal lies on the floor, slamming his head against a cabinet while Zuzka tries to carry on with normal household tasks before shutting down completely. (There’s a suicide attempt in between). Moravková is also strong, playing a mother faced with a question that has no clear answer: How do you forgive this?

Structured around long, unbroken takes, Nvotová and cinematographer Adam Suzin create an atmosphere of suffocating, overwhelming grief, trapping the viewer in a shared emotional hell with the characters. It’s executed with a kind of invisible precision — clearly the result of tight planning and long rehearsals — but it never feels artificial. Combined with two emotionally exposed performances, the film becomes something almost too intense to endure. It’s technically accomplished and powerfully acted, but so relentlessly bleak — and occasionally flirts with melodrama — that it becomes exhausting and difficult to recommend.

If all of this sounds unbearably grim — it is. (Minor spoiler ahead.) There is, eventually, a sliver of light — a hint at the possibility of forgiveness, reconciliation, maybe even new life. It’s not a profound twist, just a familiar “life goes on” trope. But after what we’ve seen, anything feels like relief.

As a person who’s easily distracted, half my brainpower is already dedicated to making sure I don’t accidentally kill my dog, who, like any child, depends entirely on me to keep her alive. Otec taps into that primal fear: not that we’ll consciously make a bad decision, just that our brain can misfire at any moment and change everything.

Editor-at-large Jared loves movies and lives with Kiki in Berlin.