Peter Hujar’s Day (Ira Sachs, 2025) isn’t much of a movie. It’s a transcript with images attached. A slight and meandering thing. A little bit of ephemera. A curio. To quote Indiana Jones: “It belongs in a museum.”

But, to be fair, it’s not really trying to be a big movie in the first place. Reuniting Sachs with Passages (2023) star Ben Whishaw, this 75-minute one-location experiment is quite literally just a reconstruction of a once-lost 1974 conversation between journalist Linda Rosenkrantz (Rebecca Hall) and the legendary photographer Peter Hujar. Letting Hujar drone on and on as he recounts the day before in excruciatingly banal detail — including the exact receptacle he uses to water his plants — it’s a celebration of the little things that make up a single day. After all, “Days are where we live.”

The problem is not that Peter Hujar is slight. It’s that it’s dull. Of course, you don’t have to match Ulysses (James Joyce 1920). It’s just incredibly tedious when your work is less interesting than any influencer podcast picked at random.

People really into the New York scene of the 1970s might find some parts interesting. Susan Sontag, Fran Leibovitz and William Burroughs’ names are casually mentioned, giving off the feel that you could walk through the Lower East Side in that era and just casually strike up a conversation with the tastemakers of the day.

And Hujar himself is a photographer certainly worthy of more appreciation. Like Mapplethorpe, he was a gay man who shot portraits in black-and-white. His method was to get up and close with his subjects and develop a deep rapport, so his photos would look past the superficial qualities and reveal something of the core. You’ve probably seen his work even if you haven’t heard of him properly; his Orgasmic Man (1969) adorns the cover of the gay trauma porn novel A Little Life (Hanya Yanagihara, 2015).

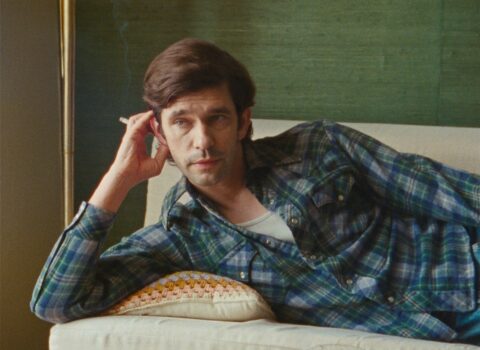

And we do get some insight into the more intricate details of working in a darkroom, of developing photos, a little something of getting his latest subject, Allen Ginsberg, to pose for photos. But little of the true passion behind his incredibly warm and interesting photos remains. It doesn’t help that the wishy-washy Whishaw is in the lead. Further distancing himself from his public image as Paddington and Q by taking on the most arthouse projects imaginable, his imitation of Hujar — from minuscule eye rolls to the way he gently strokes the couch while talking — is more a collection of physical quirks than a truly compelling embodiment of a real person. It also doesn’t help that every single line is delivered in the same monotonous way. Even the Passages propagandists will struggle to connect with this lacklustre performance here.

Redmond is the editor-in-chief of Journey Into Cinema.